Contributed by David Carrier / Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654) has been much celebrated for two generations, in a now vast critical literature. And she has had numerous museum shows, some large. Both the intrinsic quality of her paintings and her difficult and extraordinary life as a female Italian artist warrant the praise and attention are warranted. How then could the Columbus Museum of Art, which owns just one Gentileschi – Bathsheba (1635–37) – duly highlight her achievement in its current exhibition “Artemeisia Gentileschi: Naples to Beirut”? The story is remarkable.

Tag: David Carrier

Diebenkorn at Gagosian: A remarkable curatorial accomplishment

Contributed by David Carrier / For a long time, I have always thought of Richard Diebenkorn as a great painter. A couple of his paintings were in my local museum, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, where I treasured seeing them. But he was, so I believed, someone whose development was straightforward, even a little boring. I arrived at Gagosian’s large upstairs gallery on Madison Avenue with low expectations of a thick array of Diebenkorns in that one room. Maybe it had been a mistake, inspired by misguided nostalgia, to take on this assignment. In the event, the exhibition was revelatory, holding me spellbound. This is one reason why I love being an art critic – the surprise.

At the Guggenheim: Gabriele Münter’s enduring brilliance

Contributed by David Carrier / The Guggenheim has frequently presented the work of Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944). Now, finally, the museum has provided the opportunity to celebrate Gabriele Münter (1877–1962), Kandinsky’s domestic partner of ten years and a fellow founder of the Blue Rider Group – the Munish-based network of artists that pioneered German Expressionism just before the First World War.

Analia Saban’s wildly probing art

Contributed by David Carrier / Arriving at the Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, I was surprised that someone had hung a puffer jacket on the entry wall. Such galleries are usually immaculate. I walked on, for there was a lot to see in Analia Saban’s extraordinary show “Flowchart.” Upstairs, Core Memory, Plaid (Black, White, and Fluorescent Orange), a woven paint construction on a walnut frame, visually alludes to both weaving and magnetic-core random-access memory, a building block of early computing. In the downstairs gallery, five large tapestries picture playful flowcharts – hardly the traditional subjects of woven art – that marry the handmade and the digital.

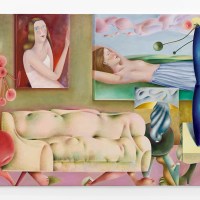

Peter Doig’s tropical opera

Contributed by David Carrier / Upon entering Peter Doig’s show at Serpentine South Gallery in London, you see Painting for Wall Painters (Prosperity P.o.S.), a vibrant depiction of a half-finished mural he photographed in the Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago’s capital city. If Henri Rousseau had actually gone to the tropics, and they had inspired him to intensify his pigments, he might have painted something like Doig’s three large-scale works, which feature sensuous, saturated colors depicting the Lion of Judah, a Rastafarian symbol, freed in the streets of the city.

The enigmatic art market

Contributed by David Carrier / We art critics are utterly dependent on the art market. Without the labors of curators, the well-dressed servants of the collector class, we would have nothing to review. I was trained as an academic philosopher, and in my home discipline money was not much of a concern. But when I made my way into the art world, I became aware of its importance. The first time I was paid for art writing, I hurried to cash the check…

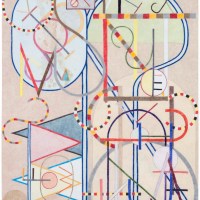

Art history diagrammed at the Milton Resnick and Pat Passlof Foundation

Contributed by David Carrier / Anyone old enough to remember Claude Levi-Strauss’s books on structural anthropology or Rosalind Krauss’ famed structuralist account of sculpture, all richly suggestive sources of art theory, will likely appreciate “Building Models: The Shape of Painting,” currently up at the The Milton Resnick and Pat Passolf Foundation and curated by Saul Ostrow. The central question he poses is how you construct a painting. In the 1960s and 1970s, when painting was beleaguered and political experimentation was a related concern, tribes of New York artists were consumed with answering that question.

Pablo Benzo smites an art lover

Contributed by David Carrier / To be a happy art critic, perhaps you need to be ready to fall in love – at least with a picture. I have a friend, a very distinguished intellectual, who some years ago fell in love with a famous work of art. He has read all the literature about this picture, written about it, and made repeated pilgrimages to see it. On one occasion, curious about his obsession, I accompanied him to take a look. I certainly admire his picture…

Spencer Finch’s inventive visual translations

Contributed by David Carrier / Spencer Finch is fascinated by Japan, which he first visited some 50 years ago, when he was a teenager. “One Hundred Famous Views of New York City (After Hiroshige),” his current exhibition at James Cohan Gallery, includes four installations grounded in that experience. Fourteen Stones, inspired by a Japanese Zen garden and made with ordinary concrete bricks, encompasses simulacra of fifteenth-century garden stones. Even these banal objects, Finch suggests, warrant contemplation. For Moonlight (Reflected in a Pond), he has installed stained glass to evoke Japanese moon-viewing. Four LED sculptures present images that recast traditional Japanese haikus through lit color schemes. And Finch’s 42 watercolors reference Utagawa Hiroshige’s renowned One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, made in 1856–58, through present-day New York.

The Tomayko Foundation: Four artists and the promise of Pittsburgh

Contributed by David Carrier / Sobia Ahmad makes silver fiber prints and inkjet images responding to Sufi traditions of poetry and oral storytelling. Her The Breath within the Breath is a 30-foot-long inkjet print on Japanese paper, mounted on a platform running diagonally across the gallery. Maggie Bjorklund does oil paintings. Her Assumption of the Virgin (After Titian) is a close-up rendering of that subject. Centa Schumacher manipulates photographic images, and her Salt Fork, Rain on Lake superimposes a white circle on an archival inkjet print. Elijah Burger had developed private codes of quasi-abstract images, like Hex Centrifuge. The unifying theme of the four-artist exhibition “I Believe I Know” that includes this work, now up at the Tomayko Foundation in Pittsburgh, is concern with transcendence. With due reference to William James’s The Variety of Religious Experience, the four artists’ shared goal is to offer visual presentations of mystical experiences. That is a familiar and traditional modernist theme, but here it receives strikingly original treatment.

The new Frick: A somewhat sentimental reaction

Contributed by David Carrier / Rebuilding seems to be a cyclical occurrence for older art museums. The collection expands, styles of display change, more capacious restaurants and shops may be needed. Older museums have to construct new galleries. To the original European galleries, entered atop the stairs at the entrance, the Metropolitan Museum of Art added space for Islamic art, contemporary work, and Asian paintings. Alternatively, a wealthy museum can rebuild almost from scratch, as MoMA has repeatedly done. Yet, for most of the time I have been going to art museums, New York’s Frick Collection has been basically unchanged, an island of stability. I remember once being shocked that one of its masterworks – Rembrandt’s The Polish Rider – was away on loan. No other major New York art institution has remained basically the same over such a lengthy period, celebrating idiosyncratic displays that mix sacred and secular works in a luxurious setting. Henry Clay Frick had a great eye.

Rachel Ruysch: Late bloomer

Contributed by David Carrier / Significant twentieth-century artists occasionally depicted flowers. Andy Warhol was one, Ellsworth Kelly another. But it’s hard to think of any major painter today who focuses predominantly on them. Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750) lived in a very different world. Thanks to the bountiful worldwide empire of Golden Age Holland, even this stay-at-home painter could obtain an amazing variety of imported flowers. The Toledo Museum of Art’s “Nature into Art,” drawn from her 150 surviving works, is, improbably, the first major exhibition devoted to her. Botany thrived in Ruysch’s time due in part to Dutch imperialism. Flower painting became a major artistic genre, and she and her rivals enjoyed access to an enormous variety of exotic flowers (and insects). Critics rightfully consider her pre-eminent. “At her best,” the catalogue says, “Ruysch painted like a novelist, creating scenes within a framework at large.“ Indeed, her intricately crafted, remarkably varied paintings convey the story of Dutch capitalism.

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva: Master of the grid

Contributed by David Carrier / Thanks to remarkably cultivated parents, Lisbon-born Maria Helena Vieira da Silva (1908–1992) was exposed to a lot of important art from early on. When she was just five, she saw the work of Paolo Uccello, a clear influence, in London’s National Gallery. Moving to France in 1928, Vieiro da Silva showed in Paris in the late 1920s and 1930s, took refuge from the German occupation during World War II in Brazil (her husband, Arpad Szenes, was a Hungarian Jew), and after the war returned to Paris, where she had a successful career. The expertly installed exhibition currently at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice aims to bring her art to the attention of contemporary audiences.

The mysterious Gertrude Abercrombie

Contributed by David Carrier / Gertrude Abercrombie (1909–1977) was a Chicago-based painter. Basically self-taught, she was inspired by Rene Magritte or perhaps Paul Delvaux to create small, highly distinctive Surrealist paintings. She was a great friend of jazz musicians and much written about by Chicago writers. She had real success in the local art market. Though gone for almost 50 years now, she has recently gained wider attention. In a deft exercise in revisionist taste, Pittsburgh’s Carnegie Museum of Art has mounted a substantial and intriguing display of her work.

“Project A Black Planet” – Enshrining a promised land

Contributed by David Carrier / Few human developments have been more consequential, in terms of both art history and broader cultural expansion, than the movement of Africans within and out of their own continent. The mammoth exhibition “Project A Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica,” now at the Art Institute of Chicago in twelve high-ceilinged contemporary galleries, includes more than 350 drawings, paintings, photographs, sculptures, installations, watercolors and prints, but also books, magazines, posters, and record albums, made from the 1920s onward. It’s a lot, but never too much.