Last Artist Standing, Sharon Louden’s compelling new anthology, features essays by a selection of artists who have managed to pass 50 and still make art. Such persistence and durability are especially impressive considering that many of their art school pals have given up the studio and resigned themselves to “real jobs” as building contractors, real estate agents, lawyers, psychotherapists, librarians, and more. Following up other books from Louden’s Living and Sustaining a Creative Life series, the new volume drives home the artist’s experience of the passage of time. If you’re over 50 and still hard at it in the studio, you’ve seen colleagues, art stars, galleries, and art movements come and go, all the while helping to sustain a perpetual community. The artists’ stories are all inspiring in one way or the other, whether they concern heartbreaks or small victories, paralyzing frustrations or major advances. But perhaps the most resonant life lesson many offer is that time vanquishes careerism. Most artists of a certain age are no longer hell-bent on impressing anyone. They’re making work simply because that’s what they love to do. The following is Susanna Coffey’s wonderfully picaresque contribution. — Sharon Butler

Contributed by Susanna Coffey / Why and how at 74 years of age am I still standing up for my art and my student’s artistic future? I’ve been painting and drawing since I was a child, and teaching for at least 50 years so it’s hard to write about all that time, all those experiences … too much information. Nothing I recount here can explain the artwork, it must speak for itself. As for teaching, the job is to shepherd students to a place where my voice will dissipate and theirs will grow strong and independent. The artist and teacher that I am is totally in love with the evolving history, craft, and materiality of painting. It lives and vibrates for me, and always has. In my own art I’m inspired to resist, compete with, and emulate traditions that began in prehistory and are morphing as we speak. In school, I seek to conserve those traditions. There will always be young artists who find that painting’s language speaks to, and for, them and see that something in its history remains undone or underrepresented.

Over a lifetime an artist’s life can be so joyful, rewarding, and full of surprises. There is some kind of gravitational pull among those who love culture. Happenstances that bring me to new friends, communities, and countries have been more common than not. But tragedies, struggles, ego-crushing failures, and constant self-criticism have also colored this life. All artists live under an uncertain star; there are no rules governing a career’s trajectory. The only guideline we can be sure of is “do the work.”

I don’t think I’ve ever walked a clear, well-lighted path. What follows, in no particular order, are a few stories about my past.

Construction sites made the best of playgrounds. At 4 years old, going to work with my father, World War II veteran Edwin Coffey, was Heaven. A wild, chaotic landscape of raw material was there for me to explore. In my imagination the mud puddles, boulders, concrete blocks, culvert pipes, piles of gravel, lots of sand, and stacks of lumber would become castles, cities, or other planets. It was ok to draw on pretty much any surface I could find. We were then living in Chittenango, New York, where dad was working on the construction of the New York State Thruway; we moved a lot in the 1950s. Although I didn’t know many other children, I don’t remember being lonely, just busy. There were a few invisible friends to play with. Sometimes dad would take me to the jobsite garage with its huge machines, colorful bins and boxes, pencils and chalks, oily smells, tools of all kinds, and a group of mechanics who always had time for a curious, talkative little girl. According to my father and his friends, when asked “What do you want to be when you grow up?” I answered, “I want to be a master mechanic or an artist.” Now 70 years later I see that I am both: a solitary, tinkering worker who maintains the tools of her trade, keeps a studio running at all costs, and creates painting after painting.

That 4-year-old who somehow knew in her bones that she was an artist had no idea about being a teacher. I hated school. My mother, Magel Willingham Coffey, a WWII combat nurse who taught her toddler to read and love books with a passion that schools seemed to disallow. Reading was a real home and haven for me. (When I visited Frida Kahlo’s Blue House, on her bookshelf I saw that she too had read Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot.) Prince Myshkin helped me endure high school. Books and stories, Miss Florence Hill read the tale of Persephone’s abduction and showed her second graders a pomegranate. I then understood in a child’s way that even gods can commit crimes and I should watch out for Hades and Zeus. The old stories, not so old really.

On October 27, 1954, my mother held a tiny baby up to her hospital window for me to see. There she was! She would be the writer Jane Carroll Coffey. Jane, my sister and friend who has, from the beginning, inspired, sustained, and encouraged me. While I struggled somewhat to relinquish my only-child status, the rewards of this relationship have always been immeasurable. Most of my memories are shared with her, sometimes corrected by her. As a toddler, I remember Jane, the future novelist, in her plaid overalls and cropped hair, propped up in front of our mother’s old Underwood, totally absorbed, pecking away at the keys. Many days we ran wild together, with our dogs Lady and Ludwig. Over fields, making forts and igloos, we played games of the imagination. Usually, we shared a bedroom. Jane’s bed was home to so many stuffed animals and dolls there was hardly room for her little self. Her ability to treat them carefully, as living things, showed me how to not lose that magical way of thinking common to most young children. Now I know she convinced me of the truth. All beings have a life of some kind, natura vivat, rather than nature morte. In 1969 she and her friend Joyce cajoled me to take their fourteen-year-old selves to the Woodstock Festival in my Volkswagen bus. I came back east, fearful, and under the sway of past traumas. But like she has so many times, Jane brought me into a truly wonderful experience. Those three days of rain, mud, and non-stop joyful music, the comradeship of Jane, Joyce, and those half-million other nonviolent attendees alchemically helped me out of a very dark place. She has been the best friend, the mentor, her words and actions have given me the ability and desire to continue.

At 21, I married a drummer. Sketchbooks were my only studio while we traveled for his gigs or lived in the “bandhouse.” There was not much time or space for me to find my artist- self but I did hear great, great music! Nights of seeing artists like Janice Joplin, Ben E. King, Sun Ra, Flora Purim, Pharoah Sanders, Muddy Waters, Jr., and others showed me how hard and passionate a real artist works at what they do. The rock & roll housewife thing was not so great but around 1973, I read The Second Sex and found Ms. Magazine, listened to every Nina Simone record I could find, and was puzzled about how I could leave that scene and become a real artist. When we lived in Providence, Rhode Island, one February day the husband dropped me off at work, emptied our joint checking account, and left the several-months-pregnant me without a word. A late-term abortion, illness, and homelessness followed, but one step, one low-wage job at a time, I crawled back into my own life. LOL, at 24 I went to a high school for my SATs in order to apply to college.

I went to the University of Rhode Island in 1973, not as a student, but as a model for drawing classes. Years later I lectured there and the professor I had modeled for joked that he didn’t recognize me with my clothes on. Modeling was a good job, I learned so much about drawing, teaching, and being still. In 1975, when I matriculated at the University of Connecticut, another professor asked me why would a woman want to be an artist when she could have babies? Seriously, Nathan Knobler? At UConn the photographer “Wild Bill” Parker took our class to a show of Bob Thompson’s paintings. In those years I was told that painting was dead but Thompson’s work showed me that painting is a continuum, a slipstream anyone could enter and experience time travel. I also got to study the art of West Africa under Tamara Northern, and discovered a canon of art in which human or animal imagery can be reconfigured and reinvented to reveal psychological, spiritual, political, and/or emotional states of being. But what was my path as an artist? As an undergrad I knew that I was, in my soul, a painter, a figurative painter. And that I loved painting but would always have something like Keats’ Negative Capability in regards to what’s missing, wrongly wrought, or propagandistic in its history.

1977 was The Year of the Snake, a poisonous year when my sister and I lost our strong, elemental, great-hearted, beloved, and loving mother to cancer. But like so many others I was driven deeper into my art by the death of the person I loved most. Images of her were what I had left and I tried to paint her back into being. 1977 was also the year a show of prehistoric figures, including the Venus of Willendorf, came to the Natural History Museum in New York. That year I also discovered the Met’s Fayum encaustic portraits. The ancient objects felt (and still feel) so immediate, so alive, so resistant to death’s erasures. That’s my sense of beauty.

Some people get up in the morning, look in the mirror, and get ready to go to work. I’m a painter who works mostly in self-portraiture, so I get up, go to work, and then spend hours looking into a mirror. This is not the place to go on about my art, I’d rather not. But there is something about these portraits that I have never talked about. I think I spend so much time looking at my reflection in order to understand that I’m still alive and in what way. In 1967, when I was 17, I was walking from Port Authority to Penn Station. At 8th Ave and 38th street in Manhattan, I was assaulted. My attacker forced me into a parking lot, was on top of me preparing to stab me in the heart when he lost his grip, and dropped the knife right by my hand. I then stabbed him in his back, he got off me and ran away and it was over but not in the way I expected. I was so sure I would die, but then I didn’t. A thread snapped. The person who poses so patiently in my studio’s mirror is one that I feel I must keep track of, she makes me uneasy. I observe that face as I paint, and work on a picture for days, weeks, months, sometimes years, until the figure on my canvas feels completely and independently, alive on its own.

At 23, divorced (whew) and finally taking my art life seriously, I made some deals with myself. I was on my own and wanted to live the kind of life I have now, that of a productive, working artist and a seasoned, engaged professor. There were very few role models in those years. The how-to for a career in art or academe seemed arcane; to thrive in both … impossible.

In New Haven, Connecticut, the late-1970s recession made it possible to find a studio space, but it was hard to find a way to support it. I’ve had so many jobs: waitress, bartender, housecleaner, chambermaid, artist’s model, nurse’s aide, file clerk. But in 1977 all the jobs were scarce and I was scraping by, bussing tables. Luckily, I applied and qualified for employment under the federal Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) and was assigned to clerical work in its offices. But what I really wanted was to be assigned to one of CETA’s arts programs for teens. Fortunately, the Theater Program’s dance instructor quit without notice, and so I became a teacher. As the only person on staff with even a little dance experience (thanks American Bandstand, Maximilian Froman, Alvin Ailey’s kid’s classes), I volunteered to step in. At that very first class, I knew a door had opened and I felt that this teaching thing was work I could do. I’ve never wanted children of my own, but I love working with young people.

Teaching is not exactly art, but it’s close to it. That season I showed each kid how to stretch, find their best moves, and introduced them to a history that they might want to become part of. That job led to other art classes. Up to and throughout my MFA time at Yale I taught painting and drawing to at-risk youth, psych patients, and incarcerated men at the New Haven Correctional Center and others.

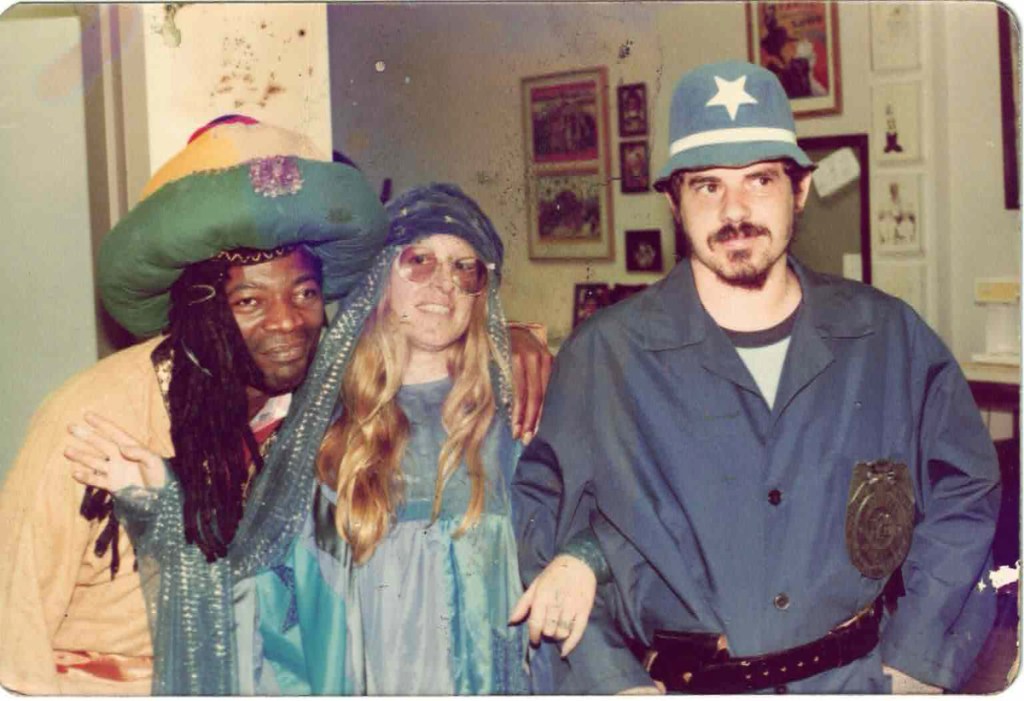

Living illegally (with my dog Jude) in a huge, unheated studio at 15 Orange Street in New Haven was possible because of those teaching jobs. Without hot water or a shower, I slept under a work table, made many bad paintings, met artist/musician friends (Riley Brewster, Lin Duer, Legs McNeil, Kyle Staver, The Saucers) and shared that space with a mime troupe (LOL, they were not quiet).

Art studios: what haven’t I done for them? Living and working in deserted buildings, with drug dealers, loud, bad musicians, and angry drunken men as neighbors. 1322 S. Wabash, Chicago, Illinois, abandoned by its owner, had no heat or electricity. The stairwell to the tenth floor was totally dark, but once I was in the studio there was 4,000 square feet of light-filled space awaiting me. At 1600 S. Michigan, Chicago, I slept with my cats on an air mattress in a loft with no secure door but with windows that looked out on the old Chess Studios and from where one could watch carriage horses run freely around a vacant lot. #1 Lispenard St, New York City, was right above an all-night bar’s sound system. On nearby Walker Street, there were lots of spaces without heat or light, but enough room to paint my first one-person show in 1994 at Gallery Three Zero in New York City.

There were others. The worst, strangely enough, was on Lake Como in a very posh residency. It was a narrow room next to the laundry and had one small window. It had a low ceiling that couldn’t fit an easel, and the floor was broken into two levels. But there I met an executor of Wittengenstein’s estate, swam among schools of silver fish under the Swiss Alps, saw snakes mating in the gardens and because there was a show to make, I made do with the studio. The memories of even my most derelict studios are so fond. I remember each one like a lover with whom I lived happily and productively but eventually had to leave.

Before 1982, I had never even been to Chicago, Illinois, but that spring, in my last semester completing the MFA Program at Yale, I was hired to teach figure painting classes at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC). Thirty-seven years later in 2017 I retired as the FH Sellers Professor in Painting.

How did I get that job? It was because I chatted with the wonderful Philip Salem outside a convenience store on York Street in New York in the summer of 1981. That July I had a work/study job on the art building’s maintenance crew. On lunch breaks we’d walk down to the Wawa convenience store for coffee and snacks. There I’d see this slender silver-haired man hanging out near the store, nursing a coffee, reading and people watching. He’d flirt a little with some of the crew. With his sly smile and such bright eyes, I liked him immediately, something about him seemed special. One day I saw him reading Jean Genet’s novel, Our Lady of the Flowers. Having just read it, I spoke with him about the book and how much I loved it. We became friends right away (I later found out he had known Genet in Europe). I learned that Philip was homeless, ate at soup kitchens, went to free concerts and movies, read library books, took long walks in the country, and lived as artful a life as he possibly could. In his youth he had danced professionally, starred in Maya Deren and Alexander Hackenschmied’s short experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon, drank too much, fell down in just about every way and found himself, in his 60s, living on New Haven’s streets.

Soon after meeting Philip I was able to find him work modeling for artists, and of course he became popular, eventually leaving the street for his own place. One day at school while waiting for some paint to dry I rummaged around the critique space looking for something to read and I found a New York Times Book Review. As I thumbed through, I found a query at the bottom of one of the pages by filmmaker Jonas Mekas, asking for information about a Philip Salem whom he wanted to interview for a piece he was writing about Maya Deren! I found Philip and the next week Mekas sent a limo car to pick him up at his shelter and wined, dined, and celebrated him. I was always so happy to make his life easier but his help to me was so substantial, he made me change my way of thinking about the future.

It was 1981 and my idea for life after graduation was to keep my studio, paint, maybe waitress, maybe some part-time teaching . . . or move to Greece, or go back to Mexico. There was no plan. But Philip uncharacteristically gave me a very harsh talking-to when he heard that I wouldn’t at least try to find a teaching job. He made me promise to go to the Annual College Art Association (CAA) conference in New York. Other classmates had set up interviews there, but with no resume or proper clothes to wear I thought, “why bother.” Philip emphasized that I MUST seize every opportunity to secure a meaningful source of self-support as he had not. So I borrowed a tweed suit, typed a resume (so thick with Wite-Out that each page looked sculptural) and shared a hotel room with several other students. Once there I looked at the lists of schools who were interviewing anyone at all, and joined those lines, the longest of which was for SAIC. After a two-hour wait, I was interviewed by professor Tony Philips, now a dear friend. It must have gone well, because they hired me for a one-year visiting artist position (that lasted 37 years). Back in New Haven, I thanked Philip with all my heart and made an asparagus omelet for a celebratory brunch.

The next year at Christmas break, driving through a blizzard on my way back to Connecticut, a huge Snowy Owl flew straight toward my windshield, it startled me and then disappeared into the forest. I wondered if I’d get to see Philip again. When I got to New Haven friends told me he had passed away quietly, in his own apartment.

Now I still paint and draw, dance, walk the wondrous Chessie “the pup” Barker, travel to see art and artists, study with master dancers, write about other people’s work, read the manuscripts of my brilliant sister, buy too many books, and adore my friends.

I’m currently making an inventory and archive of all my artwork to date, yikes. With two shows of my own work scheduled I’m also curating some shows of other artist’s work. A new series of my nine woodcut prints based on the story of Demeter and Persephone has just been published by the LeRoy Neiman Center for Print Studies at Columbia University. I’m now retired from teaching but still involved with it all. Soon I’ll be volunteering at the Planned Parenthood clinic up the street. I’m standing but not very still.

About the author: Susanna Coffey (b. 1949) is an American artist and educator. She is the F. H. Sellers Professor in Painting at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and lives and works in New York City. In 1999, she was elected a member the National Academy of Design.

What a story, dear studio floor-mate! Always things one doesn’t know. What a range-filled spectrum from alive bliss to the harrowing. A life fully-lived and being lived.

Thanks for sharing that incredible story.

Wow, I know Susanna, but didn’t know the half of it. And she skips what one would know!

I know Susanna too and also didn’t know the half of it. What a magnificent piece of writing and what an inspiring, if sometimes harrowing, life story that asks to be widely shared. I can’t wait for my daughter, a young artist, and her friends to read it.

The 418 N Clark Studio wall was immediately recognizable (I lived downstairs). The feeling and texture of her experiences manifest in this account, their generosity equivalent to her painting. The portraits along the wall form the foundation of the work she is known and revered for, and I hope the mythology paintings from that same period of time will be shown now that the mythology prints have been made. I am eternally grateful to Susanna for all she has done for me and others, and especially her painting.

Wonderful Susanna! Thank you and also to Sharon for posting it.

Very inspiring: a commitment to art through all the ups and downs

As I haven’t seen you in way way too long, it’s truly wonderful to read what a challenging and exhilarating life you have had. I treasure the one year that your studio was down the hall from mine at the Sharpe Foundation and had the privilege of seeing your work in progress. I remember calling you the “mistress of the midtone” for how expertly you managed color and value, which I learned so much from. I also love the memories you have of Wild Billy Parker at UConn.

I completely loved reading this. Thank you Sharon Butler, Sharon Louden — and most of all, Susanna Coffey.

Fantastic Article, I was in that VW Bus with Susanna and Jane and Joyce and a few others going to Woodstock in 1969. I had not seen Susanna in 50 plus years and we reconnected during shooting of a documentary on Woodstock which has been fantastic. Great Story of A Fabulous Life. Thank You Sharon and of course Susanna for sharing. ☮️❤️🎼

I loved reading this and learning new things about you and will reread and make sure everyone else reads it . You are such a natural writer . I have so much love and admiration for you Susanna.

This is such an amazing piece of writing.. always thinking about how much she has been a mentor even from afar. Thanks Susanna for sharing this, and Sharon B and Sharon L!

Commitment and inspiration to us all.

Not lucky enough to have known SC, but know people who do, this hard scrabble sketch of her restless but wonderful attitude toward making the paintings I have spent time looking hard at, this article is important. I never taught a painting class without reference to Susanna’s work. Much to deeply appreciate and hold onto. Thank you.

Oh Susanna, I wanted this piece to go on …such beauty in life lived and still living, ins and outs ups and downs…Power on, sister. Thank you Sharon for paying such attention to the lives of artists.

Susanna did everything I didn’t : Yale MFA, fancy job leading to tenure at SAiC, no kids, busing tables, looking in the mirror to paint wonderful self portraits BUT I could totally relate to her story, to every urge, every dream, every disaster, every triumph. Thank you, Susanna, for telling us so many steps I never knew about.

Stories upon stories, shared with such heartfelt detail and generosity.

Thank you dearest Susanna for all you have brought to so many of us. Remembering our first days at Yale, each of us coming from other lives and the instant recognition of a kindred spirit. A wild woman always in the music and following in the limbs. We were delighted and honored to be in the lufuki, a Ki-Kongo word, the spiritual sweat of hard work.

I recognize also, like neighbor Elizabeth Condon, the 418 N Clark Street wall in Chicago when you invited me to teach at SAIC and with Riley Brewster, for another sojourn.

And adventures with the incomparable Jane Coffey.

Not least, I’m remembering the countless gestures of tenderness, humor and delight. These same gestures translated into your painting.

Thank you Sharon B and Sharon L and

dearest Susanna for your life force, Ashé,

With Gratitude beyond words