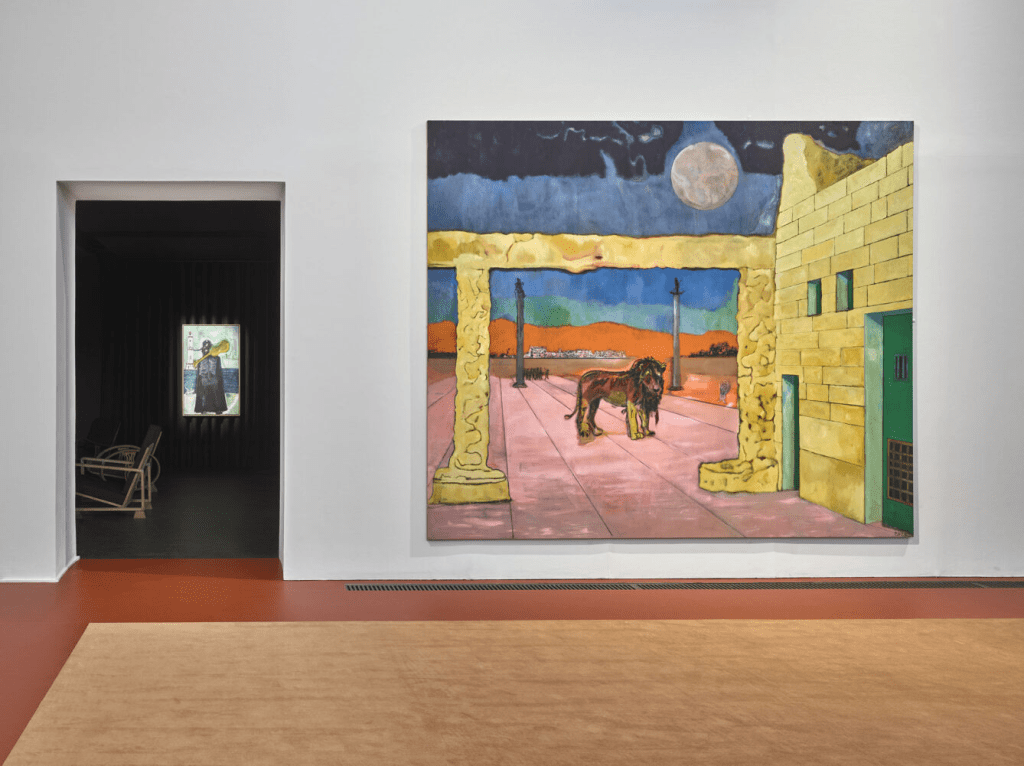

Contributed by David Carrier / Upon entering Peter Doig’s show at Serpentine South Gallery in London, you see Painting for Wall Painters (Prosperity P.o.S.), a vibrant depiction of a half-finished mural he photographed in the Port-of-Spain, Trinidad and Tobago’s capital city. If Henri Rousseau had actually gone to the tropics, and they had inspired him to intensify his pigments, he might have painted something like Doig’s three large-scale works, which feature sensuous, saturated colors depicting the Lion of Judah, a Rastafarian symbol, freed in the streets of the city. Other paintings show Trinidadian poets and musicians. In Maracas, Doig has depicted from memory a towering black sound system he spotted on the beach while exploring the island shortly after he arrived for an artist’s residency in 2000. The title of the show – “House of Music” – is drawn from lyrics of the song “Dat Soca Boat” by Trinidadian calypso musician Mighty Shadow, whom Doig admires, knew when he lived in Trinidad, and has depicted in other paintings.

Many modernist visual artists are seriously involved with music. Kandinsky was interested in synesthesia, Mondrian loved jazz, and Warhol was fascinated with rock. Nowadays, who, whatever their style of painting, does not have music playing in the studio when they are working? I fondly remember MoMA’s 2012 exhibition “Inventing Abstraction, 1910–1925,” which included atonal music played softly in one gallery. Miles Davis’ riffs accompanied a Soho gallery show. For the Doig show, Serpentine South Gallery is transformed into a listening space, akin to the hi-fi listening bars that have recently sprouted up in London and New York. While high-end speakers are now often small and inconspicuous, here the bulky retro sound system, rescued from a movie theater, is itself a graceful visual artwork. In the central room is an enormous speaker produced by Western Electric/Bell. Music that Doig has selected from his collection of vinyl and cassettes plays through a set of 1950s wooden Klangfilm Euronor speakers.

What mildly vexed me about “House of Music” was the difficulty I had recollecting the paintings. Then I recalled an essay by Roger Fry in which he puzzles over opera. The problem with the art form, he declared, is that it demands that we absorb too much all at once – not only the music and the libretto but also the painted scenery. I’m not sure Fry was completely right about opera, for the music, words, and sets are supposed to fit holistically together. But because the relationship between the music and images is less intimate in an art gallery than it is in an opera, his observation may be on target as to “House of Music.” You can only pay attention to so much at once. Precisely because the installation is so musically seductive, it’s a challenge to concentrate on Doig’s paintings. Art exhibitions are normally experienced in silence, the work displayed in neutral, white settings. That’s how curators minimize visual distraction and focus viewers on the art. The upshot is that “House of Music” is at once an excellent, deeply original exhibition and a somewhat knotty display of Doig’s paintings. Is that a complaint? Not really; it’s only to note that, cognitively, you can’t have everything.

“Peter Doig: House of Music,” Serpentine South Gallery, Kensington Gardens, London. Through February 8, 2026.

About the author: David Carrier is a former Carnegie Mellon University professor, Getty Scholar, and Clark Fellow. He has published art criticism in Apollo, artcritical, Artforum, Artus, and Burlington Magazine, and has been a guest editor for The Brooklyn Rail. He is a regular contributor to Two Coats of Paint.