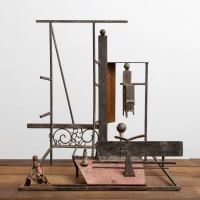

Contributed by Laurie Heller Marcus / Paint on sculpture can disrupt our spatial savvy, challenging habits of looking we bring to the interpretation of form. Lee Tribe plays with them in a variety of ways in his current show “Catching the Sun” at Victoria Munroe Fine Art. As a sculptor, he’s played the long game. Trained at a young age as a welder in the shipyards of his native England, Tribe later studied at St. Martin’s College of Art with Anthony Caro and William Tucker, a long-time friend and mentor. After moving to the United States, he immersed himself in painting, noting how marks move the viewer through the composition of an image.

Solo Shows

Will Kaplan: Stacking time

Contributed by Kate Sherman / On a freezing night earlier this month, I visited the opening of “Respawn,” Will Kaplan’s first solo show at D.D.D.D. gallery. The gallery recently traded its tight space in a Chinatown walk-up for a large, sweeping basement with a nook near the entrance, which houses Kaplan’s show. Five sizable works built primarily of wood are cleated to the walls and face the center of the room, where a provisional pedestal supports a clearly handbound notebook. Across the face of each wooden form, imagery sourced from printed matter is layered into dense collages. Kaplan’s vintage aesthetic held me back from apprehending the profusion of images present as a facsimile of our contemporary mediascape.

Robert Storr, at the margins

Contributed by Marjorie Welish / Robert Storr’s canvases are designed to counter expectations and require us to discard habitual taste. Disequilibrium reigns in abstract compositions exploiting the inexhaustible potential of the basic unit of the square. To keep the viewer alert, he employs novel moves and tactics, inserting an eye-catching red block within otherwise black and white interlocking compositions. But Storr’s paintings, on view at Vito Schnabel through January 17, are not about color, or even about perception and finesse bestowed to a surface. Rather, color for him is a signal to attend to a structural remit for composition.

Diebenkorn at Gagosian: A remarkable curatorial accomplishment

Contributed by David Carrier / For a long time, I have always thought of Richard Diebenkorn as a great painter. A couple of his paintings were in my local museum, the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh, where I treasured seeing them. But he was, so I believed, someone whose development was straightforward, even a little boring. I arrived at Gagosian’s large upstairs gallery on Madison Avenue with low expectations of a thick array of Diebenkorns in that one room. Maybe it had been a mistake, inspired by misguided nostalgia, to take on this assignment. In the event, the exhibition was revelatory, holding me spellbound. This is one reason why I love being an art critic – the surprise.

Rob Lyon’s storm-free world

Contributed by Peter Schroth / Anyone with an aversion to charm might want to sidestep Rob Lyon’s seductive show at Hales Gallery. Those seeking a diversion from the world’s traumas may find a refuge there. From Sussex, England, the artist finds his inspiration in the local landscape – a common point of reference for modern British painters. Their ghosts and others’ are clearly traceable here. Indications emerge of several additional painting traditions. Lyon borrows freely from his British forbears – note his use of rosy sand and faded blues in line with their penchant for muted palettes – but also from the Cubists and Giorgio Morandi.

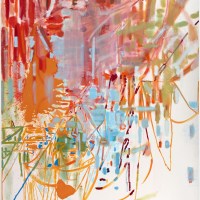

Kylie Heidenheimer’s ecstatic dissonances

Contributed by Bill Arning / Private Public Gallery has earned its reputation for mounting deeply considered exhibitions of painting that honor artists who have spent decades refining their own private grammars of mark and color. Entered through a small garden – an architectural prelude that feels almost ceremonial – the gallery offers a perfect threshold for work that rewards slow, attentive looking. “Here, Elsewhere,” Kylie Heidenheimer’s first solo exhibition there, is fully in that lineage.

Alex Katz’s seas of orange

Contributed by Tena Saw / Ninety-eight-year-old Alex Katz’s current gem of an exhibition at Gladstone consists of eleven orange and white canvases, each ten and a half feet high, that wrap around the main gallery. All reference a road in Maine where Katz spends summers. Unlike most of his work, they lean heavily towards abstraction, treating the road like an opportunity to explore perspective or the light on the leaves. Particularly if you’re lucky enough be alone in the gallery – a single room of high white walls, industrial scaffold ceiling, and enormous skylights – it becomes a kind of meditation tank, containing a sea of optical orange. Natural light settles on the paintings like a mist. The effect is more akin to that of an installation than that of a traditional painting show.

Lauren Clay’s organic sanctums

Contributed by Will Kaplan / In her solo show “Solarium” at Picture Theory, Lauren Clay compresses different scales of time into tight, enchanting wall sculptures. In modernizing the timeless form of the archway, her work reflects the structure’s progression from functional to aesthetic. The series of torso-sized works foster an intimate viewing experience, comparable to an altarpiece. Traditionally, altarpieces hover behind the altar itself. The faithful kneel beneath them for their sacraments, like the Eucharistic transformation…

Alan Butler: Data-driven

Contributed by Sharon Butler / In “Assets,” on view at Green on Red Gallery in Dublin through December 13, Alan Butler – no relation – practices what could be called digital-age synesthesia, the neurological quirk by which the senses get their wires crossed. Synesthetes may taste color or see it as numbers. While Kandinsky had the insight and talent to create arguably the first Western abstract paintings by translating music into painting, Butler has taken on a distinctly twenty-first-century project: transforming open-source digital information – stock quotes, climate data, video game coding, and other assorted online effluvia – into playful physical objects that directly engage the senses.

Betsy Kaufman: The more you see

Contributed by Jacob Cartwright / At first blush, Betsy Kaufman’s self-titled show at Bookstein Projects, a concise survey of work made from 2008 to 2025, seems simply to present a handsomely cerebral group of paintings and drawings. In time, it becomes clear that the work smuggles in something more. Kaufman’s output is a kind of two-sided coin that can oscillate between her embrace of bold, saturated color and strategies of stark reduction.

Darren Bader: Flossing

Contributed by Lucas Moran / Making sense of art is not easy. You can’t pin down meaning when it keeps moving. Darren Bader’s new show “Youth,” now on view at Matthew Brown Gallery, vividly illustrates the point. Bader has been called a prankster and an absurdist, elevating the ridiculous into high art. His earlier projects included injecting lasagna with heroin, stuffing a brass instrument with shrimp, and giving away live kittens. He provides bits of text that hint at deeper meaning while refusing to settle into it. Filling a gallery with art that plays conceptual games with history and humor and still looks good is no easy trick. But Bader pulls it off.

Karin Davie: Totally tubular

Contributed by Amanda Church / Conjuring The Cure’s 1987 song Just Like Heaven – which proclaims “you’re just like a dream” – Karin Davie’s eight new large-scale paintings on view at Miles McEnery Gallery, all oil on linen, transport us to a realm of sensation and association. Here her wavy imagery, which she has been developing in one form or another since the 1990s, immediately evokes the swells and dips of the ocean’s surface as well as recalling the fluid lines essential to the work of painters like Sol LeWitt, Brice Marden, Bridget Riley, Moira Dryer, and late de Kooning, albeit to varying effect.

Stephanie Deady and the structure of intimacy

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / Stephanie Deady’s coolly seductive oil-on-birchwood paintings now on display at Kevin Kavanagh Gallery in Dublin – all archly titled, like the show itself, Emotional Calculus – draw you in like mirages of serenity. For that purpose, they incisively deploy beauty: tawny, fluid backgrounds envelop rhythmically interacting shapes of red, blue, or white, lending each package of images visual harmony and compositional stability. In due course, the paintings reveal deeper intent, which is to complicate and enrich your ultimate apprehension of the presumptively simple life.

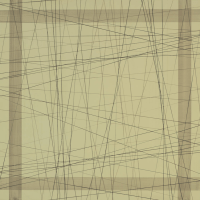

Meg Lipke’s supple resistance

Contributed by Lawre Stone / Meg Lipke makes enormity relatable. The immense Slanting Grid welcomes visitors to her exhibition “Matrilines” at Broadway Gallery. Monumental in scale, soft in countenance, this 8 x 16-foot work of painted and stitched fiber-filled muslin rises above the viewer, floating grandly along one of the gallery’s longest walls.

Clintel Steed’s careful daring

Contributed by Margaret McCann / In Clintel Steed’s show of paintings at Shrine Gallery, “Different Time Zones, Different Dimensions,” temporal experience is evoked through formal language as much as subject matter. In most, dynamic fragmentations of contemporaneity are fixed in static tessellations of paint. Richly varied shapes, packed in shallow space on dense surfaces, lead from abstraction to illusion.