Contributed by Jacob Patrick Brooks / Auxier Kline is a small hallway gallery on the fringes of Chinatown. Alexandra Smith’s previous shows there had an intimate sweetness – tender images of touch, flesh rendered in unnatural pinks and yellows, hands everywhere, faces rarely shown. “Doppelganger,” Smith’s current show in the gallery, turns into darker territory. Overall, the mood is creeping dread – a sense that “something bad is going to happen, probably to me.” Monochromatic and sceneless, the paintings evoke at once the feminist bodily awareness of Joan Semmel and the highly stylized misogyny of Italian giallo. The tension runs through the work, zipping around the room.

In “Doppelganger.” the walls are dense with paintings, a strategy that initially seems to kneecap the presentation. Large works have no room to breathe, and small, loosely painted pieces can’t whisper to each other. Paradoxically, though, this cramped installation ultimately serves the work. The forced conversation between the large and small paintings creates friction, and the lack of empty wall space heightens the claustrophobia implicit in the imagery. What could be a curatorial flaw becomes, intentionally or not, a part of the show’s unsettling power.

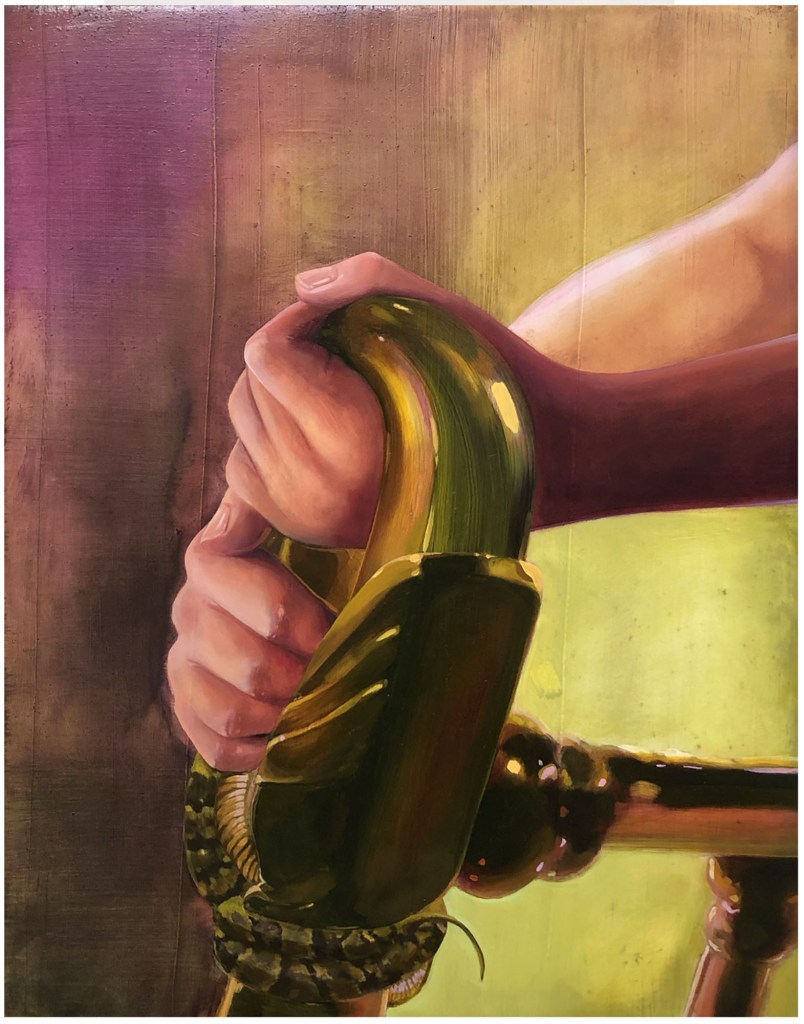

Directly to the right when you walk in, Sharper Than a Serpent’s Tooth is an early win. Two hands grip a looped, golden bed frame. Under the hands is a snake’s tail, the patterning resembling a ball python or some other constrictor. Constrictors are ambush predators that wrap around their prey and squeeze the life out of them. They are also, traditionally, bringers of knowledge, the devil’s servants, or symbols of transformation. This painting, devoid of scene or background, is pure struggle playing out in bruised washes of acidic green and purple.

To the left hangs A Woman in the Process of Becoming a Bird. Not a Bird. A Raptor. One person pulls a corset wrapped around another person’s midsection tight, crossing the string in preparation for tying. Again, a bed frame implies intimacy if not sex outright. A fire burns in scintillating orange between the figures, who themselves are depicted in pink and purple. In the hoop of the bed frame, there’s a void. The painting is large, the surface shiny. It’s not overworked but rather very considered, though the line between the two is a razor thin.

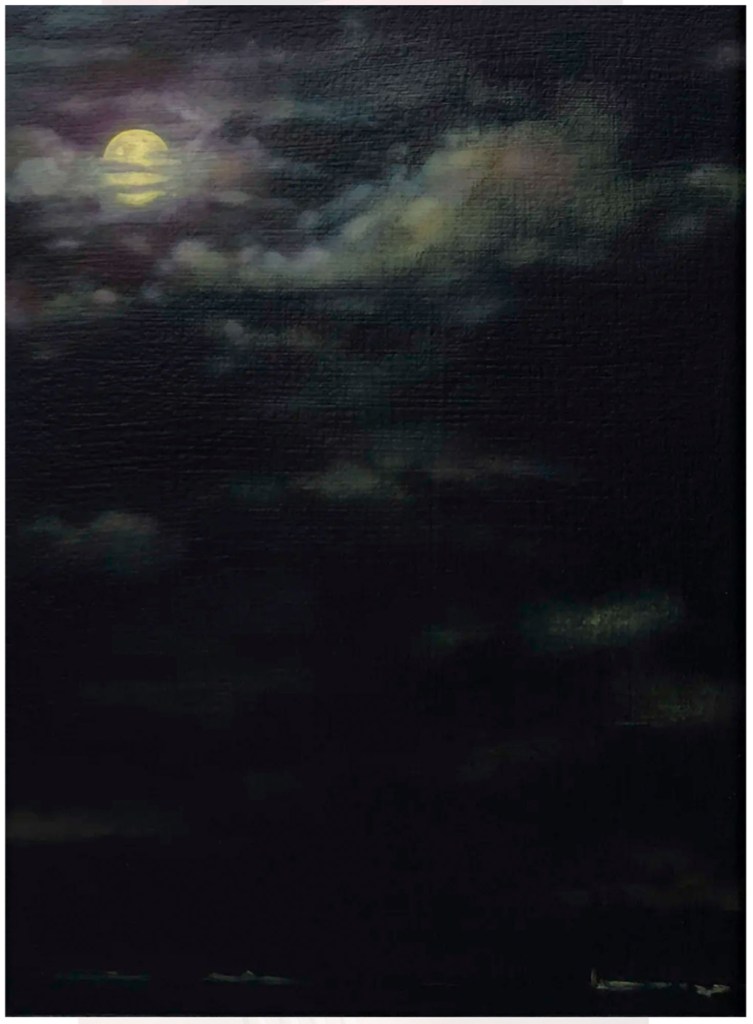

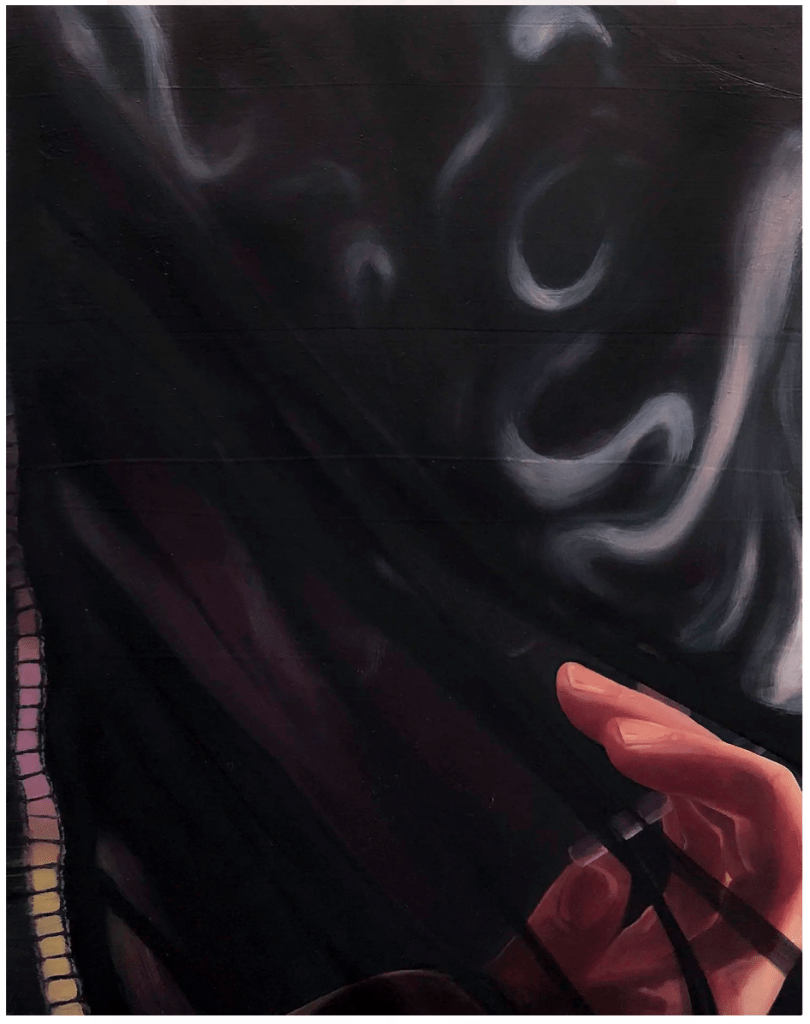

There are other successes in the room. In Pinned, a hand grips a wrist and holds an unseen body to the ground. The line between aggression and sexuality is blurred. Where this is happening is not clear, but judging from the red gradient behind the hands, it could be hell. Chandelier looks like a Ross Bleckner through night-vision goggles, too small for a big brush but crowding all the dread and morbidity of the 1980s into an 8 x 8-inch canvas.

Is there anything more contemporary than people not fucking? The tug between Semmel and Suspiria has been done so much that reprising them might feel wrong and dated. Yet Smith genuinely appears to be wrestling with influences and images as much as the protagonists of her paintings are. She fears going too far or not far enough. The overarching drama is the larger impulse to self-censor. As you walk the gallery, you ask: Will she go for it? What’s stopping her? Smith is willing to walk right up to the line, but she still says, “I don’t know.” Even so, her willingness to take us this far, this skillfully, is a triumph. In her next show, maybe there will be more room to breathe, and maybe she will make something just a little bit more fucked up.

“Alexandra Smith: Doppelganger,” Auxier Kline, 19 Monroe Street, New York, NY. Through November 7, 2025.

About the author: Jacob Patrick Brooks is an artist and writer from Kansas living in New York.