Contributed by Lore Heller / “MILK TEETH,” the title of Kate Hargrave’s show at Karma, implies both permanent loss and permanent gain. One gains milk teeth as a baby and loses them as adult teeth take their place. If children place them under their pillows, fairies might bring rewards. Losing milk teeth is losing childhood, developing permanent teeth coming of age – reminders to parents that time inexorably arcs life. Joni Mitchell observed that “we’re captive on the carousel of time,” and my grandmother’s lullaby, “toyland, toyland, beautiful boy and girl land,” reminds us that “once you cross its borders you may never return again.” Hargrave, who painted this work as she raised two children, captures this pervasively bittersweet quality.

Solo Shows

Felix Beaudry’s malleable boys

Contributed by Bill Arning / There is something wildly compelling when an installation flips on you—reversing itself in meaning and affect if you linger more than five minutes. Felix Beaudry’s “Malleable Boys” at Situations is one of those shows. On first entry, oversized, lumpy, monstrous heads loom and encircle you like funhouse demons. They feel nightmarish—deformed, melting, mid-metamorphosis into dangerous humanoid creatures. But stay a beat longer and the menace softens. They become almost cute, like huggable, overgrown Cabbage Patch Kids—less terrifying than misunderstood.

Pinkney Herbert: Unsettled

Contributed by Paul Behnke / Pinkney Herbert’s exhibition “In Between” at David Lusk Gallery regards a painting less as a finished image than something unfolding in time. The title points to a place of transition where matters are not fully settled but are still taking shape. Herbert has long divided his time between Memphis and New York, and itineracy seems to carry into the work. Structure, rhythm, color, and pace energize paintings that never completely resolve. Across the exhibition, Herbert denies the viewer a stable place to land. Lines shift direction, forms collide, and constructs loosen almost as soon as they appear.

Jenny Lynn McNutt: Nativity of squirms

Contributed by Jason Andrew / At the New York Studio School Gallery, Jenny Lynn McNutt’s exhibition “Touch Me” reclaims figuration in ceramics as a matter of urgency rather than nostalgia. With an immediacy that heightens their corporeal impact, McNutt kneads together cultures and rituals embraced during her travels to West Africa, China, Eastern Europe, Ireland and Italy. The 20 sculptures representing a decade of work embody forms twisting, crouching, bracing, and blooming in what the artist aptly describes as “a nativity of squirms,” which captures both their generative vitality and their refusal of repose.

Polly Shindler’s natural reverie

Contributed by Lawre Stone / Known for painting interior spaces and domestic objects, Polly Shindler shifts her subject to the rural Hudson Valley landscape for her exhibition “Valley Music” at Deanna Evans Projects. Images of mountains, flowers, and fields hang in sequence on the walls, like a roll of snapshots taken from the car window. Shindler’s paintings do speak to the compulsion to pull over to the side of the road, take out the phone, and hope to capture the elusive, astonishing beauty of nature. Complementing the landscapes are larger, close-up paintings combining flower heads, stems, and leaves with abstract elements. Schindler’s flowers grow from the ground, with wispy stems and simplified blooms reaching for otherworldly skies. Painting in a full Crayola color array, she plumbs the sublimeness available every day.

Mitchell Kehe’s targeted irresolution

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / The title of Mitchell Kehe’s solo show at 15 Orient – “Bonded by the Spirit of Doubt” – encapsulates the ambiguity and contradiction in which he traffics. Doubt is fundamentally divisive and isolating, a fraught source of any bond in the sense of affection or solidarity. Maybe he means “bonded” in the sense of “certified,” the way American whiskey is, uncertainty and doubt being such pervasive phenomena that no work of art can claim validity or integrity without somehow imparting them. In his beguiling paintings, this idea is manifested in a casual tension

Alex Kwartler: Open to the world

Contributed by Shirley Irons / In a dream, I asked Alex Kwartler if his work was about the unreliability of images. God no, he yelled. “Off-Peak,” his current show at Magenta Plains, presents modestly scaled paintings that read across the room like music, with beats and rests, highs and lows. Their subjects include tender representation, stark pop, painterly abstraction, tin can lids, dots, drains, and shipwrecks. They echo and repeat. Their consistency lies in his assured, skillful paint handling. When you can do anything with paint, why not just do it?

Choong Sup Lim: Eastern ode to a Western city

Contributed by Ben Godward / Choong Sup Lim says that he doesn’t paint his sculptures but rather finds the color in the city. This might be the most important aspect of his show “Yard” (Madang) at Shin Gallery. Color as form – in this case, linen and detritus from the city – yields a pallet of neutrals. Linen, the substrate of painting with a capital P, takes a star turn here. Much of the show consists of raw linen, and it is as important in the sculptures as it is in the paintings.

Hedda Sterne’s infinite space

Contributed by Jason Andrew / Hedda Sterne was the only woman made famous by Nina Leen’s photograph The Irascibles for Life magazine in 1951, and the group’s last surviving member when she died at 100 in 2011. While many of those featured in that iconic photograph achieved mythic status, Sterne was consigned to the margins of art history. “I am known more for that darn photo, than for 80 years of work,” she once remarked. Implausibly inventive and unwilling to adhere to a single style nor embrace prevailing aesthetic trends, Sterne didn’t cast herself in the heroic mold favored by the brooding boys associated with Abstract Expressionism.

Anne Russinof: More than a gesture

Contributed by Michael Brennan / Anne Russinof passed away a year ago at the age of 68. “Gestural Symphony” is a commanding memorial retrospective of her mostly large, emphatically gestural paintings. Posthumous exhibitions are by nature bittersweet, but Russinof’s resists melancholy because her work is so irrepressibly lively. Her signature outsize curves are sweeping and springy. They kick, bounce, and jump around.

Trisha Donnelly: The real thing strange

Contributed by Talia Shiroma / The drawings in Trisha Donnelly’s show at the Drawing Center are a succession of curving volumes with meticulous shading, depicting what are most aptly called not objects but “things.” They suggest sinew and bone, heavy metal aesthetics, and the errant, automatic doodling found on classroom desks or tucked away in notebooks. Neither representational nor abstract, some recall Jay DeFeo’s works from the seventies in their effects of translucency and particularized strangeness. Yet unlike DeFeo’s apparitional tripods and dental bridge, the things which Donnelly depicts rarely seem to coincide with physical reality, to mystifying and sometimes numinous effect.

John Kelly: The body is never abstract

Contributed by Bill Arning / In the mid-1980s, great art experiences of every conceivable stripe seemed to bloom prodigiously and organically from a single club on Avenue A called the Pyramid. Out of this dark, sticky-floored dive came a motley congregation of artists, musicians, drag queens, filmmakers, and poets who launched shockingly original cultural provocations that still reverberate globally, even though relatively few people witnessed them at the time.

Anne Wehrley Björk: Where sharks once thrived

Contributed by Jonathan Agin / Formed by erosion over millions of years, Chaco Canyon was the site of the Ancestral Puebloan people’s sprawling urban center. Buildings erected there in the eleventh century were among the tallest in North America until the nineteenth. These remote, enigmatic ruins, marked on early Spanish maps, were rediscovered in the modern era by US Army surveyors after the Mexican-American War. Today they are part of the Navajo Nation, which covers parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. When Anne Wehrley Björk was a child, her family used to take her camping there. As demonstrated in “Lost Canyon,” her new show of paintings at Margot Samel, she has never forgotten the landscape.

Laura Newman: Flatness and the illusion of depth

Contributed by Adam Simon / A photographer friend once asked me why painters are always talking about the space in a painting. He wanted to know what this term “space” meant. I talked about the different ways paint on a flat surface could be made to suggest depth, and how the challenge for modern painters was to create depth while also reaffirming the flatness of the support. I probably referred to the elusive concept of the “picture plane” and how simultaneously maintaining mutually exclusive ideas – flatness and depth – could produce a poetic or even a mystical dimension in visual art. Most abstract paintings present shallow space, keeping depth to a minimum. This type of painting is usually non-hierarchical; nothing feels more essential than anything else. The viewer’s eye tends to scan. If you want to both represent depth and reaffirm flatness, shallow space is going to be easier to handle than deep space.

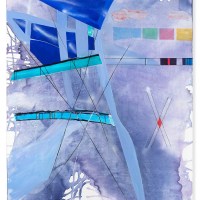

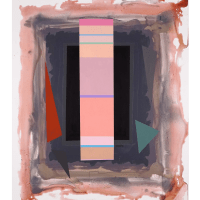

Peter Plagens’ portals and vortexes

Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / At Nancy Hoffman Gallery, Peter Plagens’ bracing new abstract paintings don’t so much as invite you in as dare you not to enter. Each canvas consists of three basic components: a painted frame of washy gray or brown; a pristinely rendered hard-edge shape, assertively opaque, centrally positioned, vertically symmetrical, and horizontally striated; and scattered, seemingly directional slashes. The second feature propels the paintings, but the other two steer them. The distinctly dilute vagueness of the frames might impart risk, the pesky shards impulse, and the vivid, intuitively color-coded ramps expansive fate – humble versions of Jacob’s Ladder, vouchsafing a future that need not be feared, at least distantly echoing one of Dave Hickey’s blithely peremptory and eminently arguable mantras: “Beauty is and always will be blue skies and open highway.”