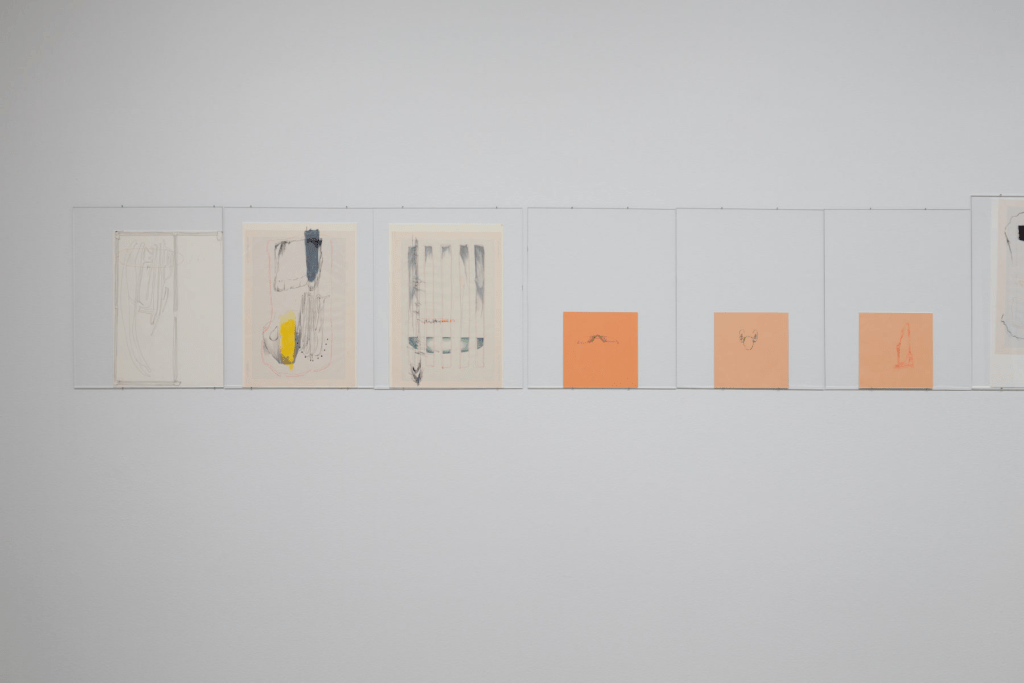

Contributed by Talia Shiroma / The drawings in Trisha Donnelly’s show at the Drawing Center are a succession of curving volumes with meticulous shading, depicting what are most aptly called not objects but “things.” They suggest sinew and bone, heavy metal aesthetics, and the errant, automatic doodling found on classroom desks or tucked away in notebooks. Neither representational nor abstract, some recall Jay DeFeo’s works from the seventies in their effects of translucency and particularized strangeness. Yet unlike DeFeo’s apparitional tripods and dental bridge, the things that Donnelly depicts rarely seem to coincide with physical reality, to mystifying and sometimes numinous effect.

One particularly vivid example, installed near the entryway, describes in sensitive detail a nameless, hovering thing which appears as a corroded metal breastplate or a decaying piece of vellum. The image’s indeterminacy is at first unmooring and leaves the drawing appearing oddly incomplete. Yet in providing no answers, it opens up the aesthetic experience to the viewer. From a certain angle, the effort is romantic, bypassing the mediation of language in order to bring you closer to the sensuous. From another, it is remote and analytical, laying your process of perception on the operating table. There are shapes resembling spidery runes, carefully modeled forms that appear like leathery organs or crumpled steel, an image I could only think of as a “wounded pillow”—things which tempt language, then blithely contort or escape it.

Donnelly is known to work across mediums and the senses, a tendency largely excluded from this exhibit. Still, the drawings prompt questions around perception: the relationship between mental images and objects, the difference between an image as a thing in itself and as a representation of a thing. What struck me about the drawings is their sense of being virtual and factual at once, recalling both the inchoate substance of images formed in the mind’s eye and the pedestrian solidity of things perceived externally. A work installed in a corner, inscrutable and charming, consists of a pocket-sized video of a small, vibrating orb projected onto the bottom half of a drawing of slender prongs. The two images appear to exist in separate dimensions, which the mind struggles to integrate; yet for all their material difference, neither the drawing nor projection seems to have any more claim to substance than the other. And after all, the work might ask, why couldn’t a drawing not just simulate light and movement but embody it literally?

Perhaps due to their thing-like nature and reticence, the sensibility of the drawings sometimes reminded me of the deadpan allure of Jasper Johns’s maps and flags. But even more so, they recall the hazy, associational accretions of Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons. In their shading and variable densities, one senses the threshold of a mental image becoming material, gaining substance and presence through the accumulation of marks and, concomitantly, the movement of the pencil and the passage of time. Donnelly has said that her drawings “relate to objects the way that you listen to the radio, if you have a radio on,” and perhaps this oblique act of relation (tuning in, tuning out) is what accounts for the works’ facticity yet strangeness. It is as though they record the transmission of environmental stimuli from sensation to the flickering mental forms they take, arriving on the page like afterimages, already fading.

Throughout the show, I thought of Adrian Piper’s essay on “the real thing strange,” her account of the moment where cognition stalls in the face of the unfamiliar. “The things may cause the blankness,” she writes, “but it is the blankness that reveals the things—the unfamiliar phenomena, the experiential anomalies that temporarily suspend the ongoing functions of conceptualization, and that we therefore fail to cognitively recognize at all.” Such an experience is characteristic of Donnelly’s work—elliptical, aphasic, wary of discursive capture. The show’s brief text, which quotes from chapter six of the Tao Te Ching, is preceded by the declaration “the unspeakable”: as the ineffability of the Dao, one supposes, so the ineffability of aesthetic experience. This style of aphorism might prompt eye-rolling, particularly among those less sympathetic to its sentiment. Yet if there is a place for the irrational and the unknown in aesthetic experience, then Donnelly’s work is among its strongest defenders.

“Trisha Donnelly,” The Drawing Center, 35 Wooster Street, New York, NY. Through February 1, 2026.

About the author: Talia Shiroma is a researcher and writer living in Brooklyn.