Contributed by Jonathan Agin / Formed by erosion over millions of years, Chaco Canyon was the site of the Ancestral Puebloan people’s sprawling urban center. Buildings erected there in the eleventh century were among the tallest in North America until the nineteenth. These remote, enigmatic ruins, marked on early Spanish maps, were rediscovered in the modern era by US Army surveyors after the Mexican-American War. Today they are part of the Navajo Nation, which covers parts of Arizona, New Mexico, and Utah. When Anne Wehrley Björk was a child, her family used to take her camping there. As demonstrated in “Lost Canyon,” her new show of paintings at Margot Samel, she has never forgotten the landscape.

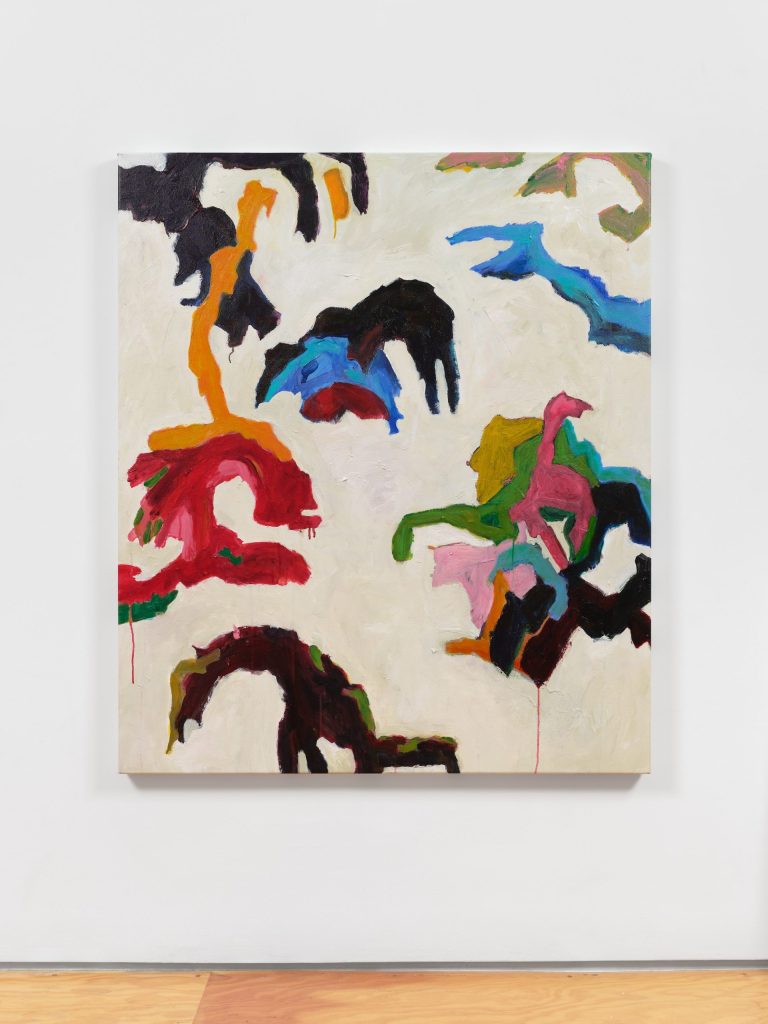

In highly saturated hues of teal, vermillion, and brown against earthy beige backdrops, Björk arranges free-flowing animal silhouettes as if communicating in an ancient petroglyphic language while evoking canyon topography. The figures fight, rest, and love within each painting. Life is spirited and messy here. The colors blend and break apart. The acrylic paint is allowed to drip, though in one place it’s laid on so thick a wood stirrer gets embedded in the canvas.

Awls and needles, hammers and saws, and other tools of craft and industry have been uncovered among the ruins of the Great Houses of Chaco – nine high-ceilinged, multistory buildings built in the ninth through the twelfth centuries. This complex, the social system it embodied, and the hundreds of miles of trading roads extending from it are known as the “Chaco Phenomenon” – the culmination of thousands of years of human activity in the canyon. There remain unanswered questions about the precise nature of this Chaco culture, posed by its rich petroglyphic practices and massive, astronomically aligned constructions. Björk’s work explores those questions.

Black, azure, and vermillion figures seem to rise and fall together, moving and transforming like biomorphic clouds. In Carp, white negative space illuminates the fractal geometry of ancient river networks, which some believe inspired the masonry of the Great Houses. The composition of Murmuring is skewed towards the top half of the canvas. Orange- and brown-tinted whites mix with chalkier hues in places. The figures are lankier, extended horizontally, layered across one another like rock strata. They resemble hawks, snakes, bison, and salamanders. Some may hark back to the oceanic prehistory of the American southwest, where sharks once thrived.

Lost Canyon is the most prepossessing piece in the show. A blot of tangerine is impastoed on red like a blossom. Brilliantly colored figures of all sizes range across the canvas, with black Klee-esque calligraphic lines swirling behind and across them. Across Chaco Canyon’s walls, thousands of petroglyphs are still visible. In her high-contrast, exuberant paintings, Björk seems to challenge the artificial separation of visual art and writing, of image and word, and to capture a timeless spiritual essence.

“Anne Wehrley Björk: Lost Canyon,” Margot Samel, 295 Church Street, New York, NY.

Through February 14, 2026.

About the author: Jonathan Agin is a New York-based literary agent.