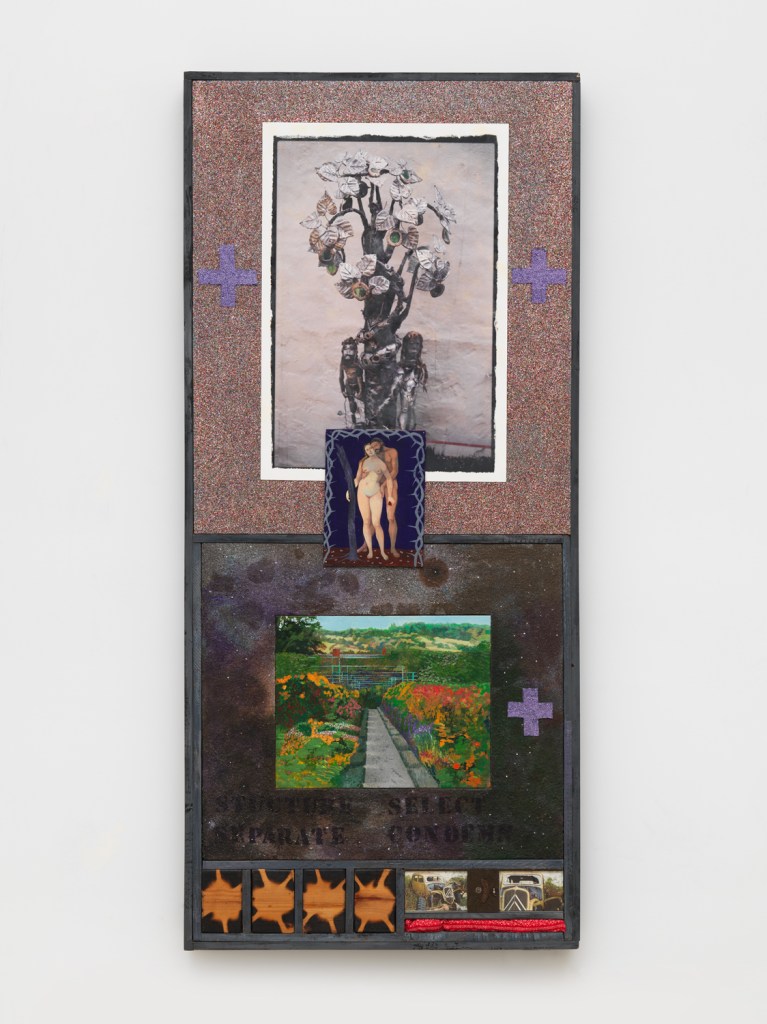

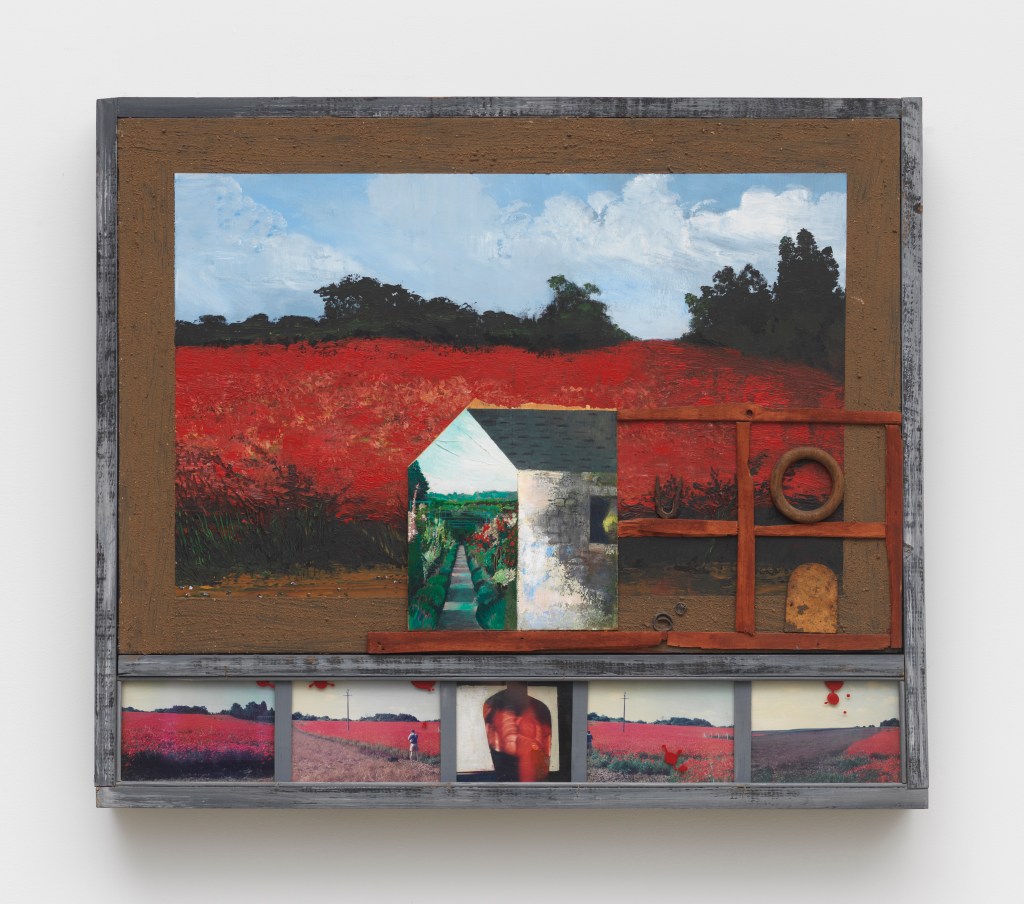

Contributed by Adam Simon / Paul Gardère (1944–2011), whose work is now on view in “Second Nature” at Magenta Plains, is known for a unique version of combine paintings, incorporating assemblage, found objects, photography, dirt and glitter into works that critique the legacy of colonialism in Haiti and its diaspora. The problem with this narrative is that it undersells how formally innovative his work was in its time, the degree to which it stems from his own biography, and how it anticipated our current multi-screen reality.

A member of the creole Haitian bourgeoisie targeted by François “Papa Doc” Duvalier’s “noiriste” regime in the 1950s and 1960s for being too Francophone and European, Gardère was forced to leave Haiti when he was 14 and did not return for 19 years, becoming an American citizen soon after that. The complexity of Gardère’s biography found an equivalence in the hybrid nature of his work. He had a subtle relationship with Haitian culture. He used both Christian and Vodou imagery, adopted the frontal, gridded format of much abstract painting, shared in the disjunctive, postmodern esthetic of his contemporaries in New York but also nodded to Monet, Degas, and Claude Lorraine. His paintings weave together different narrative threads but can be experienced all at once, visually synthesizing seemingly incompatible forces.

To fully engage with the work at Magenta Plains, it might be necessary to reconsider aspects of how we look at art, specifically the path of increasing reduction that visual art has been on for the past hundred years or so. Less is more; the gestalt is everything. Even pictorially intricate paintings tend to resolve into a singular statement or overall image. With a few exceptions – certain paintings of Jasper Johns come to mind – one must go back to Dutch Vanitas paintings of the seventeenth century to find works as demanding of exegesis as Gardère’s. It is his insistence at having so many interrelated parts, merging the autobiographical with historical, the political with esthetic, the formal with symbolic, that distinguishes these works. And it is the fact that these are not narrative paintings that makes them such compelling inventions. The diverse images come to us synchronistically, without temporal order or hierarchy. An inventory would include Vodou and Christian imagery, pastiches of nineteenth-century paintings, photographs he took and ones he found, random attached objects that we are tempted to interpret. His work poses juxtapositions of conflicting cultures that evoke the writing of Frantz Fanon or Edouard Glissant, but these paintings are not illustrating ideas. Rather, they are emanations of an inner world borne of complicated circumstances. The temptation to “read” Gardère in such a way that every attached object or rendering of Monet’s Garden (where Gardère was in residence in 1993), every photo, and every erotic component is interpreted as symbolic may conflict with the subliminal nature of these works. In a 1999 interview with curator Alejandro Anreus for an exhibition at the Jersy City Museum, he said:

I cannot ignore Vodou any more than I can ignore the art that I find in the museums of America and Europe. This is a complex issue, one that I believe to be relevant not only to artists who have immigrated to Western contexts but also to those who are working in the Caribbean, since that culture itself is permeated with elements that originated in the West. Yet I do not set out to paint Vodou icons, nor do I seek to illustrate Vodou ideas. I do utilize a wide array of strategies (appropriation, pastiche, parody, etc.) that are part of the resources of contemporary artists.

Certainly, a critique of colonialism is part of his oeuvre, but I wonder if an attempt to make sense of his own individual life isn’t equally so. Gardère was situated between Haiti, France, and the United States, between European culture and the indigenous culture of Haiti, and between Christianity and Vodou. His use of dirt, glitter and wooden planks is in keeping with the collagist esthetic of painting in New York at the time he was working there, but also evokes his homeland, suggesting early memories. His many inclusions of the cross which in Christianity refers to Christ’s crucifixion but in Vodou to the meeting of the human and spirit worlds, also evokes the paintings of Kazimir Malevich. If this layering makes sense, it points to the way that Gardère, who studied at Cooper Union and Hunter College and was in residency at the Studio Museum in Harlem, aspired to make art that acted on a viewer without recourse to interpretive texts and was finally a singularly visual experience. Yet his art resonates with anti-colonialist thinking and with questions around the shaping of identity. In suggesting that these works might require a reconsideration of how we look at art, I meant that they require a reconciliation between multiple components and their resolution as a singularity. And this brings me to their timeliness: the works in “Second Nature” surely anticipated the multi-screen world that we inhabit, the conflation and simultaneity of disparate information streams that now seems normal. There is a related need for thinking that can accommodate conflicting realities. Gardère did this pictorially.

“Paul Gardère: Second Nature,” Magenta Plains, 149 Canal Street, New York, NY. Through October 25, 2025.

About the author: Adam Simon is a New York artist and writer. His most recent solo painting show was at OSMOS in 2024.

This is a Beautiful body of work and a wonderful mix if disparate influences. When I was in Miami, before the gold rush, there were some beautiful artworks there from Haiti, which has such deep spiritual roots in tragedy and transformation. The kind of work that makes me wish to be a collector instead of an artist!