Contributed by Michael Brennan / As a boy, the sculptor Tony Smith – a canonically important and under-appreciated American sculptor who connects AbEx and Minimalism, equally at home with Pollock and Serra – suffered from tuberculosis so severe that his father built him a small shed in the backyard of their South Orange, New Jersey, home, with fiberglass curtains to minimize dust and a small black stove. Smith lived in the spartan outbuilding for several years. Imaging him there might elicit the melancholy that Van Morrison conveys in his aching ballad “T.B. Sheets.” As an adult, however, Smith noted an upside, at least for an artist: “If one spends a long time in a room with only one object, that object becomes a little god.” I grasped the significance of this observation acutely when I encountered Mark Dagley’s sloop-like sculpture Vāyu-Vāta, which, pointed away from a black radiator and darkly mullioned window, dominates the Abaton Project Room in the Financial District.

Vāyu-Vāta is the name of a Zoroastrian deity of wind and atmosphere – as Dagley describes it, a “god of the wind and a divine messenger found in both ancient Sanskrit and Persian texts” acting “as an interface between the worlds of good and evil.” Some may find this this politically amusing, given that Dagley’s sculpture is sited not far from Wall Street. The piece stands about knee-high, and is made of copper-painted steel, prop glass, and painted plywood. Its shape recalls a child’s paper airplane. It is lying in a bed of broken glass cubes; perhaps a glass ceiling was broken. The copper and glass are on top of a white painted truss, which features the regular intervals that one would see beneath a subway platform.

The white truss rests on what appears to be an ordinary packing crate, albeit a well-crafted one, with faint traces of glitter in the wood sealant. The crate looks as if it could house the sculpture itself, which imparts a sense of nesting, sharpened by the placement of the sculpture within the space. Without doing the math, I would say the area around the sculpture is about equal to that occupied by the sculpture itself. Kazimir Malevich, the Suprematist godfather of abstraction, often used this deceptively simple compositional device to emphasize an artwork’s iconic status.

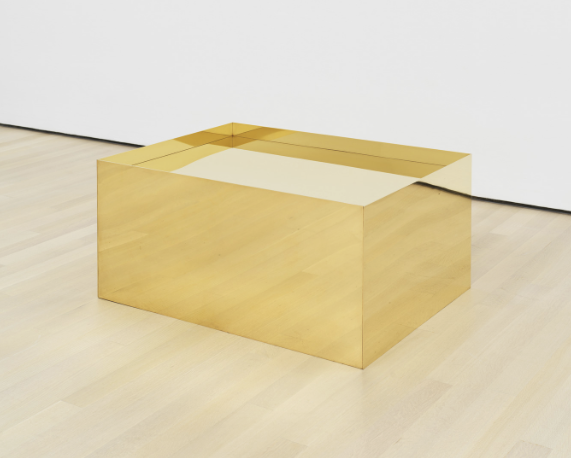

There’s a lot of copper coping around Brooklyn, lining old schoolhouses and aboveground subway stations, but it is rarely shined to a polish because it turns green via oxidation – like the Statue of Liberty – so quickly. This might seem a magical quality, and I think this notion is baked into Vāyu-Vāta, which, again, references a deity. As we learned during the Covid pandemic, copper is naturally antimicrobial, which could imply purity or untouchability. At the same time, in American culture, it is associated with modest hucksterism; consider the Tommie Copper compression clothing that supposedly heals, hawked on TV. A great pleasure of seeing Vāyu-Vāta is its polished copper finish. Even Donald Judd’s brass box sculpture at MoMA is typically grubby, covered in fingerprints, by the end of a week. Vāyu-Vāta arguably has more in common with Judd’s organic plywood sculptures. Like the post-modern architect Michael Graves, Dagley invigorates the modern look by eclectically combining contrasting styles.

Abaton Project Room is an offshoot of the multifaceted Abaton Book Company, founded by Dagley himself and writer and producer Lauri Bortz, his partner. Abaton Project Room is their second public exhibition space, following the legendary Abaton Garage in Jersey City, now closed. Vāyu-Vāta is the second show in a yearlong program. Artists exhibit work in every neighborhood of New York City, but generally not so much in the FiDi. That could be changing, following the great impact and legitimizing force of Christopher Wool’s recent renegade show “See Stop Run” on Greenwich Street. We are almost at the point, thankfully, where a room is a room is a room. This collective realization could be a solution to an otherwise stricken gallery system that underserves many artists and viewers.

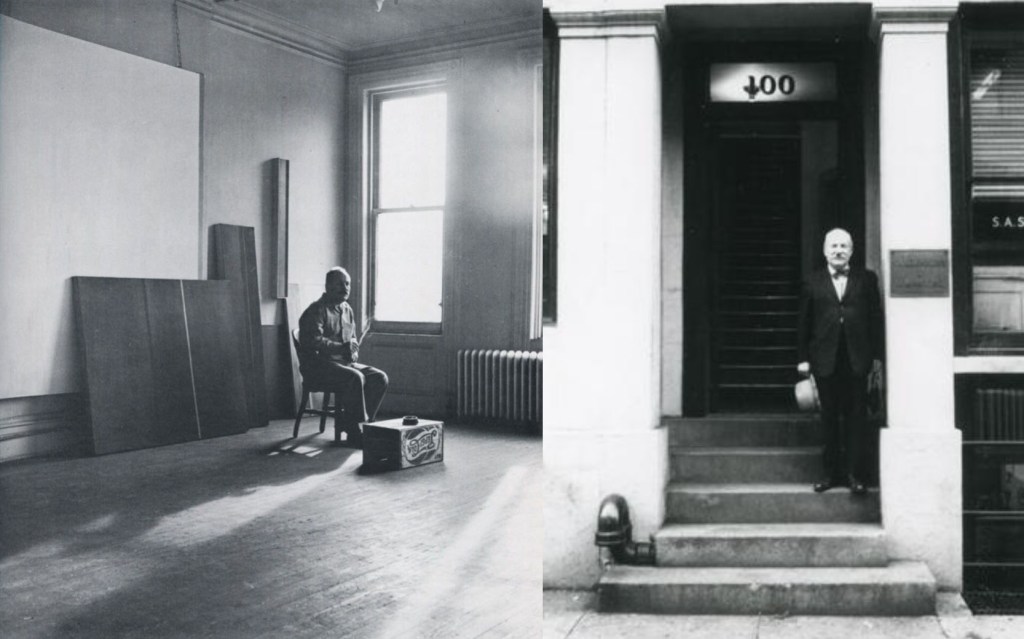

I felt a little funny making my way to the FiDi, where I rarely go, to look at art. I kept thinking about Barnett Newman’s forlorn downtown studio at 100 Front Street. I never met him – he died in 1970 – but did spend an afternoon with his wife, Annalee Newman. My trek to Abaton turned out to be a kindred experience. Vāyu-Vāta was not the only object in the gallery. Behind the desk, Dagley had hung a lithograph of Newman’s titled Barnett Newman/Frank O’Hara Sleeping on the Wing, from 1967. I suspect Dagley, like me, was conscious not only of the wings that the two pieces share but also of Newman’s nearby former studio.

The idea of venturing into to the FiDi to see a single sculpture and a print may seem silly to some. To me, though, seeing a single thing done right is infinitely preferable to slogging through an abundance of discordant work in a slew of multicast art fairs.

“Mark Dagley: Vāyu-Vāta,” Abaton Project Room, 11 Broadway, Suite 965, New York, NY. Through September 9, 2024.

About the author: Michael Brennan is a Brooklyn-based abstract painter who writes on painting.

Another exceptional review by Mr Brennan, interesting tie in to other artists and time periods.

Thanks Mr. Brennan for a perceptive review. The way you tie in other artist and time periods enhances the intensions of this work

Sensitive review – thoughtful observations. And a pleasure to read!