Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / Esteemed in Germany during the Weimar Republic but branded a “degenerate artist” by the anti-modern Adolf Hitler, the great expressionist painter Max Beckmann fled Nazi Germany to Amsterdam and continued to paint. Returning to Germany after the war may have struck him as craven or at least psychologically unsustainable, and he emigrated, as many European refugees did, to the United States. When he arrived in New York in 1949, aged 65, he had, as it turned out, only about a year to live — he would die of a heart attack — and nothing to prove. But he loved the city, and evidently it inspired him. Confronted by an art scene dominated by the Abstract Expressionists, and having no truck with abstract painting, he just kept doing what he’d always done: painting narrative and acerbically observant scenes of life keyed to the human figure, often his own, sometimes as an element of remarkably assured and phlegmatically grotesque allegory.

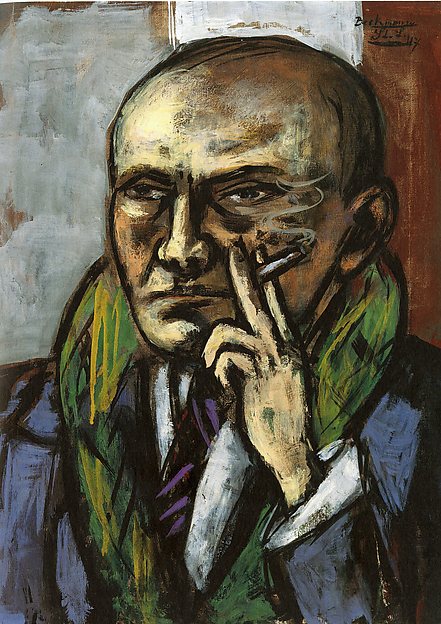

Beckmann’s penetrating intensity did not relent as he aged, and it is well captured in the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s superb exhibition, bluffly titled “Max Beckmann in New York,” of his New York paintings and some earlier ones held in public and private New York collections. His heavy, preternaturally confident brushstrokes and thick color make all his figures look immovable, and integral to the otherwise inanimate scenes in which they appear. The expressions tend to be stern — see, for instance, Self-Portrait with a Cigarette (1923) — and the figures seem to be planting themselves so as to assert a specific intention, perhaps a right, to be in a particular place at a particular time.

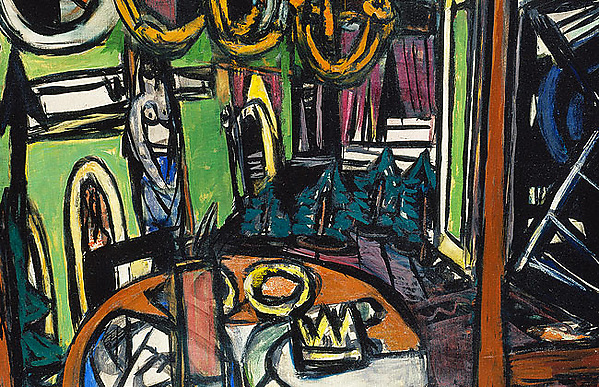

In this spatial and temporal urgency, Beckmann’s work is about as far from pastoral as painting gets. The Met’s show devotes one room to paintings he made when he was exiled in Amsterdam. When he could, he would go to parties, cabarets, and the theater as a respite from burgeoning instability. Once the war began, he never forgot that violent conflict was consuming the continent, so his paintings of such diversions sometimes show not gaiety but rather imagined moments of anguish in the mere trappings of leisurely indulgence. Even before he left Germany, he sensed the impending collapse of civic order in Paris Society, in which the German ambassador to France is in the foreground of a party clutching his head in his hands.

The artist reserved some softness for paintings of his beloved wife Quappi. The dominant register of his work, though, is not affection or warmth but judgment, possibly moral and certainly emotional. Falling Man, a gem Beckmann produced in 1950, depicts a virtually naked figure plummeting from a skyscraper, exposing the arrogance lurking in the modern and, incidentally, foreshadowing 9/11 and Don De Lillo’s novel of the same title about that event.

More elaborate works, in particular Bird’s Hell (1938) and the triptych Departure (1932-35), are overtly historical and darkly political, informed by his experience of Nazi rule and perhaps more remotely his service as a medic in World War I. For all that, Beckmann substantially escaped the demons of, say, an Otto Dix. It’s plain from these paintings that Beckmann appreciated the finer things in life — good food and drink, elegant clothes, and pretty women. But if beauty hardly revolted him, his lyricism remained eloquently and unequivocally qualified.

“Max Beckmann in New York,” curated by Sabine Rewald. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Upper East Side, New York, NY. Through February 20, 2017.

Related posts:

Dix Mix

German history paintings: Dix, Grosz, Beckmann, Meidner and Steinhardt

——

NOTE: Our 2016 Year-end Fundraising Campaign is underway: Please consider making a tax-deductible contribution to support Two Coats of Paint in 2017. Thank you. Click here.

——