6 x 9 inches

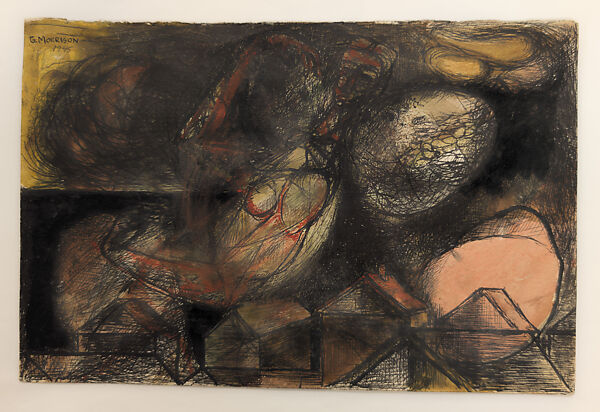

Contributed by Laurie Fendrich / Before going to see “The Magical City: George Morrison’s New York” at the Met, I did not know a Native American artist had been part of the Abstract Expressionist movement. The 35 works in this exhibition include paintings and drawings made during Morrison’s two stints in New York – the first in the late 1940s, when he was in his early twenties, the second in the mid-1950s – along with paintings from his 1980s Horizon Series. The best paintings come from the artist’s New York years, when he was committed to full abstraction. The Antagonist literally stopped me in my tracks. Consisting of vertical red and orange forms set against a grid of muted green and blue-green squares, the painting has a lovely slow motion to it. The Red Painting – dedicated to Franz Kline, who hung it over his bed – is another stunner, featuring a jagged, yellow horizontal line and blue lines rising from the bottom that disrupt the otherwise red ground. Landscape, New York, with five abstract, blob-like shapes arranged in a moon-like landscape, is one of several alluring Surrealist riffs.

22 x 50 inches

11 3/4 x 9 inches

The third of twelve children – only nine survived to adulthood – Morrison grew up in an impecunious but apparently happy family in a town near the Grand Portage Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe Nation, a Minnesota reservation. He spoke only Chippewa until he went to public school at age six. When he was nine, he was sent to the Hayward School for Indians in Wisconsin, one of the country’s many assimilationist boarding schools whose purpose was to de-culturalize indigenous children by replacing their language with English and their traditions with White Christian values. A year later, Morrison developed tuberculosis of the hip and, after surgery, spent 14 months with both legs in full casts. He passed the time reading, drawing, and making carvings. Having had a childhood illness that confined me to bed for several months, I appreciate art is a child’s way of enduring its implacable unfairness.

34 1/8 x 50 1/16 x 1 3/4 inches

When he returned home, Morrison had a permanent limp and was socially withdrawn. Luckily, he found art mentors at the local public high school and won a scholarship to the Minneapolis School of Art. He was awarded a traveling scholarshipupon graduation that enabled him to study painting and drawing at the Art Students League in New York. At age 24, he moved to New York, which he called “the Magical City” because of its bright lights. Later, he told Hazel Belvo, the painter he married in 1960, that New York made him feel he was “a citizen of the world.”

During his years there, Morrison showed alongside such artists as Lois Dodd and Louise Nevelson, knew Jackson Pollock from going to the Cedar Bar, and befriended Kline, who also had a bad leg and who became godfather to his son Briand Mesaba Morrison. He appeared in multiple group exhibitions, including Whitney annuals and some in venues outside the city, and received some critical attention. In 1948, when de Kooning first showed at the Egan Gallery, Morrison had his first solo at the Grand Central Galleries. Neither flaunting nor denying his Indian heritage, he frequently attended Native performances and visited Native American friends. But New York let him feel the modernist, universalist spirit, and he was particularly inspired by Jungian ideas about the unconscious. Though he had a Chippewa name, he signed his work “George Morrison” throughout his life.

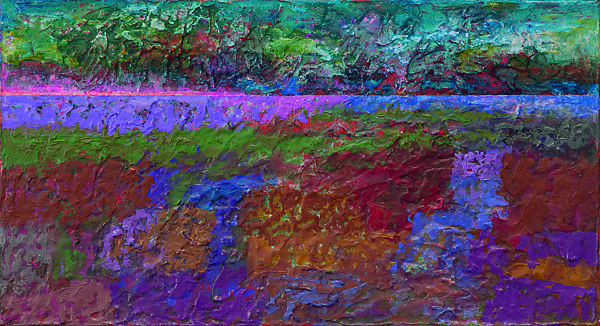

After spending a year in France on a Fulbright fellowship, Morrison returned to the United States in 1953 and taught at a few schools before circling back to the state of his birth in the 1970s to teach fine arts and Indian Studies at the University of Minnesota. Retiring in 1983, he spent the remainder of his life at a home and studio he had built on the Chippewa reservation. Going home, he said, made him feel “the need to put certain Indian values” into his work. A newfound autochthonous consciousness changed him from “a painter who happened to be Indian” to a painter who wanted his Indianness to show up in his paintings. He strove to evoke “Big Water” – the Chippewa designation of Lake Superior – in a painting such as Morning Storm, Red Rock Variation: Lake Superior Landscape. The horizon line and choppy brushstrokes do precisely that.

acrylic on board, 6 x 11 inches

The contemporary Native American painter Kay WalkingStick wrote that Morrison “never made art with feathers and beads; he did not paint ponies and war bonnets; he did not paint about identity politics.” He was, she said, an Abstract Expressionist. My take is a little different. Morrison eschewed Indian tropes and identity politics, but at a certain point he ceased being simply an Abstract Expressionist, allowing his Native American culture to infiltrate his work and becoming, for lack of a better term, a Native American modernist. He had two distinct identities, each of which he explored at different times in his life, that yielded distinct bodies of work. How significant a contribution Morrison made to Abstract Expressionism is hard to gauge, but, regardless, his rich oeuvre is worthy of renewed attention.

“The Magical City: George Morrison’s New York,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1000 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY. Through May 31, 2026. Curated by Patricia Marroquin Norby (P’ urhépecha), Associate Curator of Native American Art in The Met’s American Wing.

About the author: Laurie Fendrich is an abstract painter and arts writer who lives in Lakeville, Connecticut. She is represented by Louis Stern Fine Arts in Los Angeles and is a frequent contributor to Two Coats of Paint.

Thank you, Laurie, and Two Coats for bringing so vividly to life another show that, alas, I will probably never see. This guy is a marvel!

Yes, thank you for this. Abstract Expressionism seems to have been such an alluring panacea to symbolic/illustrative representation of identity at that time. I believe Jack Whitten spoke of this. Looking forward to seeing the show and more brought to us by P’urhépecha (Patricia Marroquin Norby). I am so hopeful about the changes and additions being made to the American Wing.