Contributed by Michael Brennan / Many conceptualists, favoring the unconstrained and expansive, balk at the representation or framing of any experience as image. Long after he abandoned painting, the late installation artist Robert Irwin likened it to a mere “keyhole” of perception. In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig declared that compartmentalizing experience for viewing made you “a passive observer” for whom “it’s all moving by you boringly in a frame.” Yet surely not every living experience has to be as open-ended as a motorcycle racing across salt flats. While a painting can never capture the full immensity of life, with adequate perception and economy of means – say, Luke Howard’s vision of the sky realized in paper and watercolor – even a diminutive one can provide a meaningful distillation of experience. The paintings of Eleanor Ray, now on display in her third solo show at Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, constitute abundant evidence.

Her paintings are small, mostly under ten inches in their longest dimension. They defiantly reside in keyhole territory, but she has a keen sense of scale. The art world routinely misuses this term to signify anything large, when in fact it concerns relative size. Ray has an uncanny aptitude for gauging it, and thus harmonizing a painting’s internal proportions with its physical dimensions and objecthood. Her paintings are exactly the size they need to be. If they were any larger, they would lose their surface tension and density, hence their tactile concentration of experience, and appear slack.

When painting professors – I’ve been one for over 25 years – have nothing especially incisive to say in a critique, they often default to, “Make it bigger.” Bigger is not always better. Giacometti, Manet in his later years, Morandi, Vuilliard, and now Ray, among others, prove it. She challenges the tyranny of the stock 5 x 7-foot Chelsea painting, and for good cultural reasons. We now live in the age of face-to-face engagement with cellphones and screens, not giant-finned cars and Cinerama. Smaller is often smarter. If Ray kicked in the door, there may be enough artists who are currently working small to follow her through it and coalesce into an actual movement. Tomma Abts, Dana DeGiulio, and Tony Mascatello come to mind. In any case, it’s a relief to see work of a size appropriate to the artist’s intent, and not just inflated because paintings’ value and decorating potential have come to be determined by the square inch.

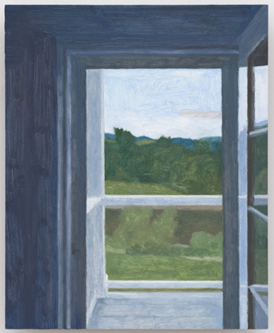

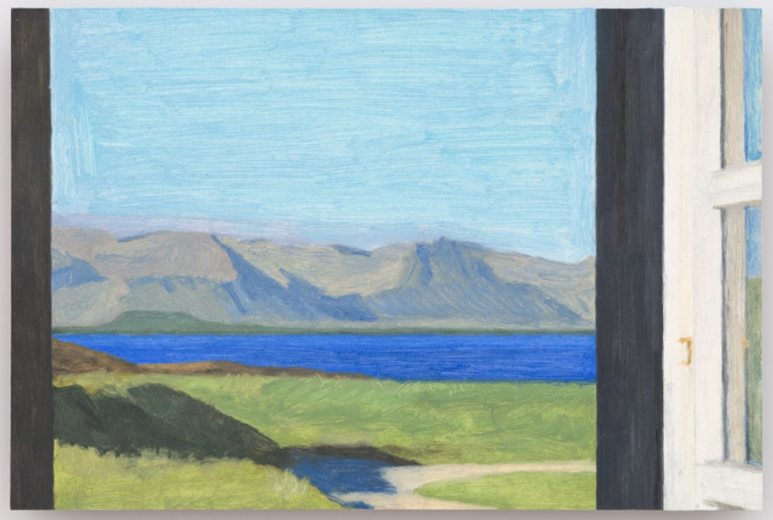

Ray has a studiously considered sense of composition, revealed in her fondness for structurally defining forms such as doorways and windowpanes. Many of her images appear framed in the manner of a cinematographer.

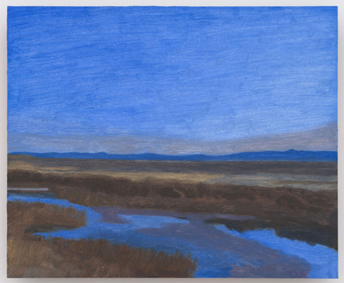

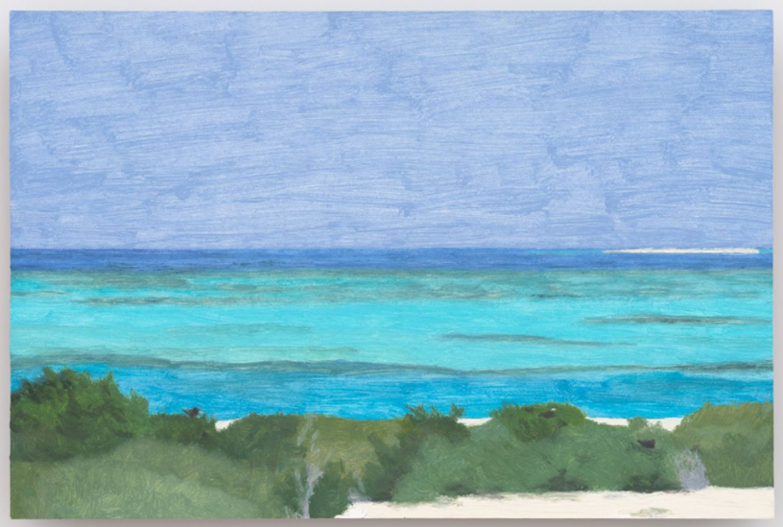

Hellnar window and Vermont door are so tenderly painted that any slight break in the direction of Ray’s super-fine brushwork becomes an atmospheric event. Because she paints on panel, her brushwork, though quiet, tends to sit visibly on the surface, with no canvas weave to sink into. She favors a lightly threaded surface and silken color lone, often manifested in flat, softly painted horizontal passages.

Ray uses a broad range of lapidary blues, from cobalt, to ultramarine, to aquamarine. At times, her glowing use of the color is reminiscent of Patinir, the Dutch master whose blue rocks and seemingly infinite vistas marked the beginning of landscape painting as a genre. Because most of her images are reconstructed from memory, Ray’s work is a bit dreamy, approaching but never reaching realism. Her power of recall would appear to rival the remote viewing skill of government spooks detailed to the Army’s Stargate Project.

The installation reflects Dia-level rigor by way of precisely calibrated intervals and imaginative juxtapositions that avoid formulaic grouping. Frieze-style hanging, with holes in the wall, lends authoritativeness to the small paintings. Ray is a disciplined painter, as well as a rigorous writer on art. If anyone has doubts about the endless renewability of painting or its persistence of vision, her work may well assuage them.

“Eleanor Ray,” Nicelle Beauchene Gallery, 7 Franklin Place, New York, NY. Through November 16, 2024.

About the author: Michael Brennan is a Brooklyn-based abstract painter who writes on art.

NOTE: We’ve just kicked off the first week of the Two Coats of Paint 2024 Year-end Fundraising Campaign! This year, we’re aiming for full participation from our readers and gallery friends. Your support means everything to us, and any contribution—big or small—helps keep the project thriving into 2025. Plus, it’s tax-deductible! Thank you for being such a vital part of our community and keeping the conversation alive. Click here to contribute.