Contributed by Jonathan Stevenson / Brooklyn-based conceptual painter Adam Simon is known for his cagey synthesis of the graphic symbols and tropes of commerce and civic life into elegant visual statements about the zeitgeist and, more grandly, the world as a whole. He can use text to penetrating effect, as in the small paintings he made a few years ago superimposing the edict “STEAL THIS ART” on the vintage silhouette of a policeman. In one not-quite-Hoffman-esque line and an evocative image, he captured the ambivalence and limbo of the art world between the establishment and the counterculture, having himself cultivated a live community in that space by organizing, with several other artists, the collaborative “Four Walls” events in Hoboken in the 1980s and Williamsburg in the 1990s. In “Great Figures,” his solo show now up at OSMOS, he has continued in a searchingly ironic vein, now with a bemused fretfulness that affords it epochal resonance.

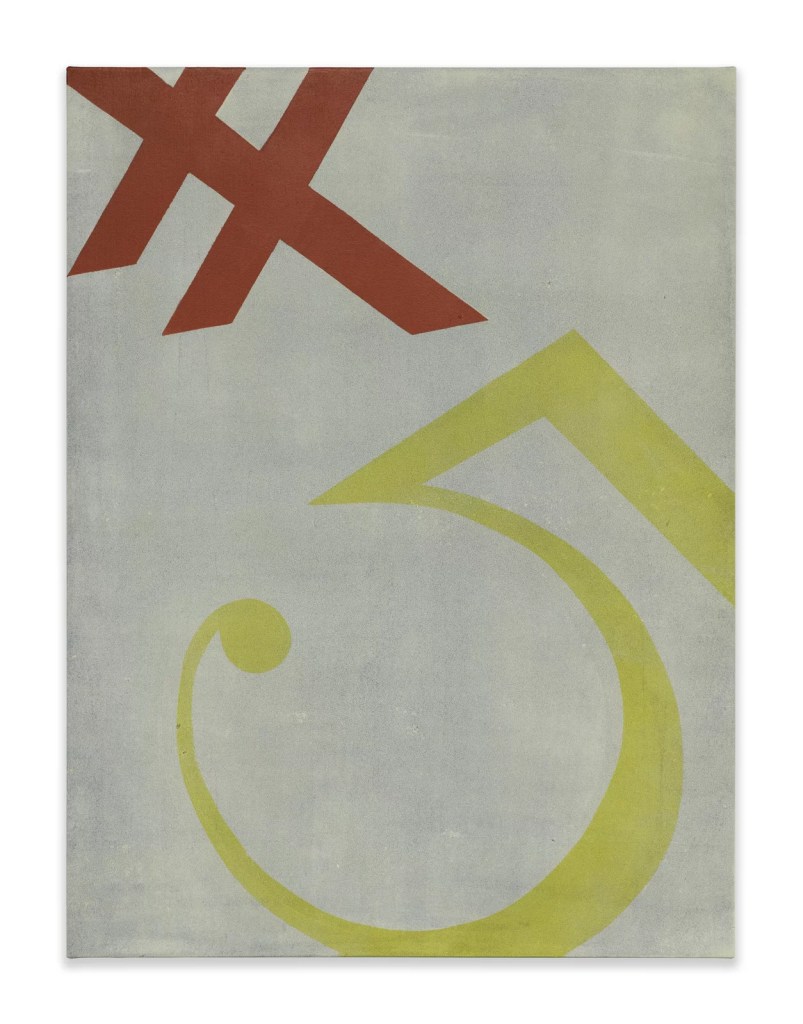

48 x 36 inches, 121.92×91.44cm (Image by Alon Koppel)

Before delving into content, it’s worth noting the conceptual tightness of the series’ structural and compositional elements. Most of the canvases are medium-sized, which allows Simon optimal room to hone an allusive brand of abstraction, between representation and obscureness. He still cites the vocabulary of commerce, but by way of paraphrase rather than direct quote: his imagery is not as mapped and tethered as it once was, stimulating the viewer’s intuition rather than begging for identification. A masterly handler of acrylic paint, he uses mostly subdued colors and a matte affect to plant an attitude of insistent and authoritative – but never shrill or sanctimonious – observation, tinged with tentative sadness that could be topical or just for days gone by. Mounting the canvases on wood panels confers declarative firmness without grandiosity. Together these features generate the warm yet formidable vibe of the casual oracle – not merely a fly on the wall, but shy of a strident polemicist. From that vantage, the title of the show might be a bit sarcastic, gently casting Tolstoyan doubt on the great man theory of history.

The Great Figure, effectively the title piece and keynote, presents an outsize, serifed numeral 5, uncomfortably large for the visual field that the artist has allotted it, and a fragment of the Exxon logo encroaching on the picture plane. Probably the most straightforward piece of the bunch, the figure is lifted from I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold, a 1928 Charles Demuth painting that uses imagery from William Carlos Williams’ poem The Great Figure. Whereas Demuth fixes on the energy of the city, Simon perceives its enervation, the painting’s subject drifting off the canvas. Probing thoughts about art and life hover more mysteriously – and ominously — in other paintings. In Agog and Magog, what could be an inviting chaise longue and a predatory grey ghost loiter in counterpoise, innocence and spite waiting to clash on a greenish gray field. Obliquely related is the unmistakably mournful I Misspoke, in which a receding figure still faces a hand waving goodbye across a mottled grid of complication. Pointed juxtaposition short of didacticism, often along a diagonal axis as in these two pieces, is an ingrained and highly effective Simon practice, also on display in Bransanto, High and Low, and Tic for Tac, and sometimes implicating nature and human foible.

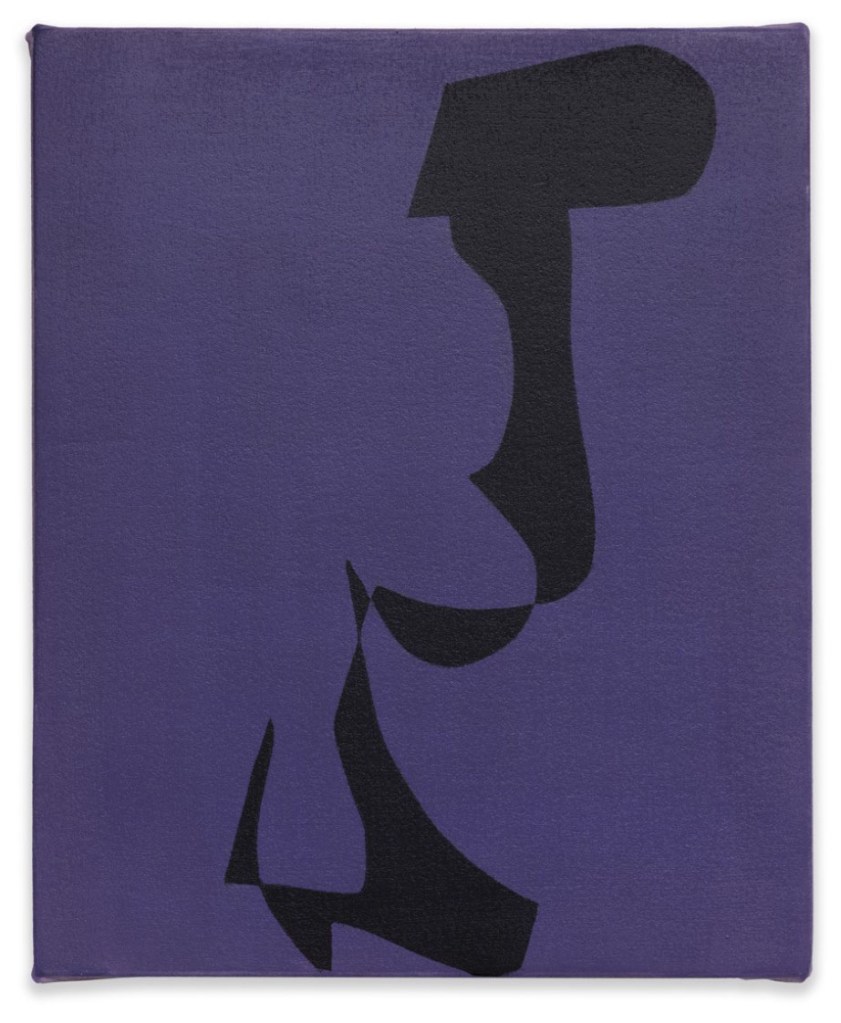

48×36 inches, 121.92×91.44cm (Image by Alon Koppel)

This exhibition is a veritable essay, encompassing subtly different narrative tones and devices. Departing from the juxtaposition format, Gloaming is quietly portentous, suggesting a half-decipherable horse and rider stalking a highway in a twilight mist with unknown intent. Remnant seems to reference a human form, to similar effect. Smaller “cluster” canvases (along with the very fluid As Much As) are less differentiated and capture the general mood of existential jostle, flux, and instability more holistically. The exceptionally bright Funferall and the enigmatic Trousers Rolled, dark but with one little Turner-esque red flourish, provide sardonic reassurance that it isn’t all bad, while the elegiacally blue Seesaw by Neatlight, perhaps a coda of sorts, settles on an equitable balance between momentary play and redemptive mission.

48 x 36 inches, 121.92 x 91.44 cm (Image by Alon Koppel)

Warhol, the most celebrated artist to have explored the infiltration of popular culture into the individual psyche and the collective unconscious, arguably had the luxury of finitude. Exponentially less information was readily accessible in the 1960s and 1970s – the world was still analog – so the metaphorical power that Marilyn, Mao, and camouflage exerted covered a lot of cultural ground. The overarching forlornness of Simon’s canvases and their defiant simplicity hint at a longing for that kind of manageability. As civilization became more fraught and complex in the twentieth century, Samuel Beckett concluded that James Joyce had exhausted what literature could contribute to larger understanding by way of an abundance of words, so Beckett took it upon himself to see what he could add with very few. Maybe Simon is trying to do something analogous with his spare yet loaded, and decidedly analog, paintings. Whatever their source or rationale, “Great Figures” works impressively as both a wistful cultural reflection and a prospective cri de coeur.

“Adam Simon: Great Figures,” OSMOS, 50 E. 1st Street, New York, NY. Through November 9, 2024.

About the author: Jonathan Stevenson is a New York-based policy analyst, editor, and writer, contributing to the New York Times, the New York Review of Books, and Politico, among other publications, and a regular contributor to Two Coats of Paint.

Quiet excellence. Thank you.