Contributed by Laurie Fendrich / If theres one word that sums up Paul Czanne (1839-1906), the subject of a massive exhibition at MoMA, its struggle. But struggle in art is so 20th-century. Artists in this century dont believe in it, choosing instead to make their art from theories, ideas, or political positions. For such giants as Matisse and Picasso, however, Cezanne was the father of modern art, and for many artists of my generation, he is a continuing inspiration.

This beautiful and carefully curated exhibition of 250 works on paper (and a few oil paintings) draws from multiple public and private collections. It includes individual drawings and watercolors, not to mention drawings from nineteen sketchbooks. The exhibition borders on overwhelming, but it has a valuable takeaway: Czanne took on the Herculean aesthetic task of being honest and original all in one blow.

MoMA claims in the press release that the show reveal[s] how this fundamental figure of modern artmore often recognized as a painterproduced his most radical works on paper. Perhaps. What matters, though, is discovering how Czannes eye, mind and hand worked. For example, a somewhat aberrant pencil drawing from a private collection titled, Still Life: pain sans mie [a kind of bread] (c. 1887-1890) is, according to the label, just about the only Czanne work that includes text and (no surprise) it drew the particular attention of Picasso and Braque. The letters on the window and outlines of the bottles are described by Czannes famous repetitive, broken contour lines, which function as a kind of live recording of the artist as he worked to accurately depict whats in front of him. The left side of the drawing is a mirror reflection. Were left with his deep sense of ambiguity about whats solid and whats fleeting.

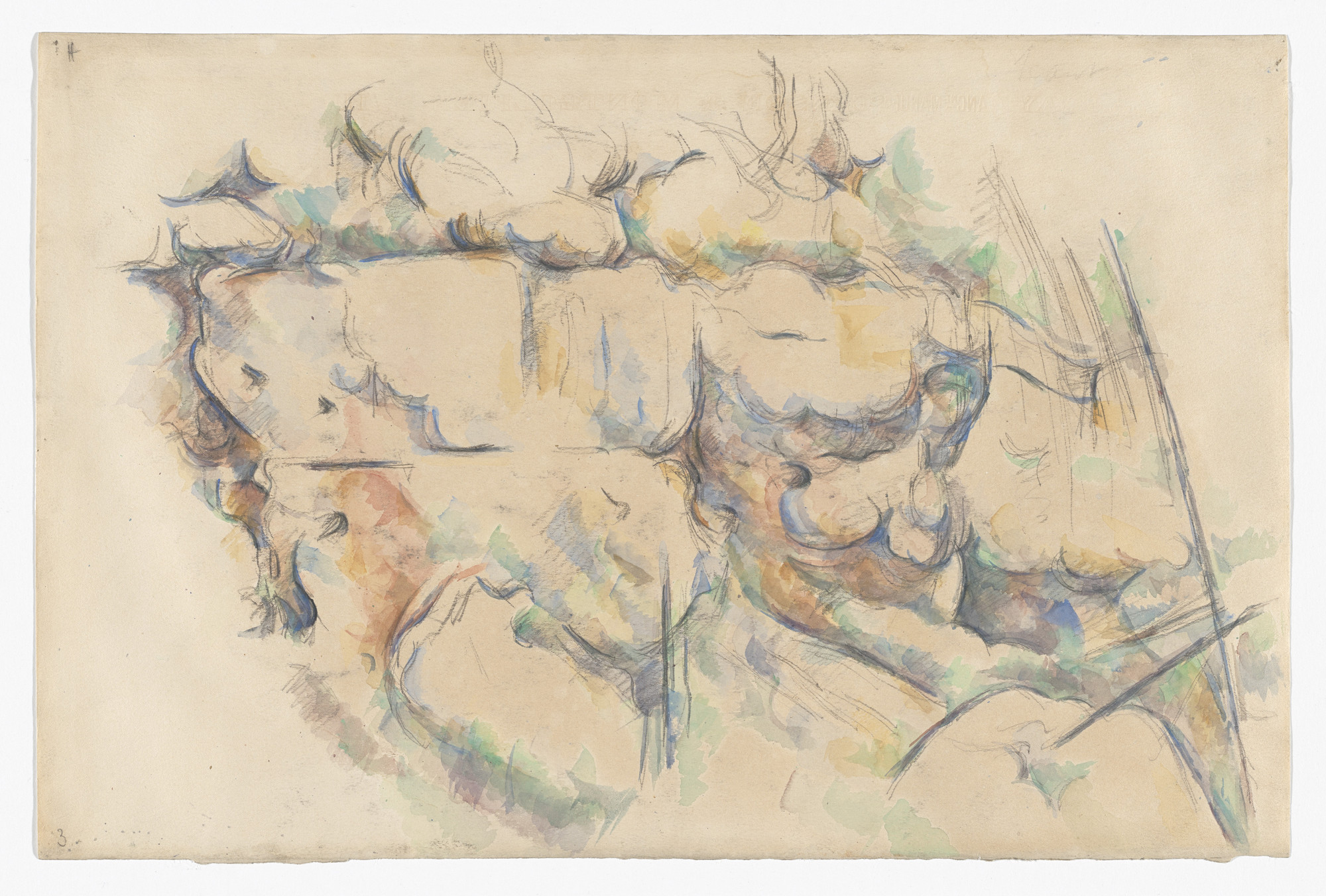

In Rocks Near the Chteau Noir, a watercolor c. 1895-1900, the connection to the artists oil paintings is clear. In its equally spaced placement of square shapes, were reminded of the many oil paintings where Czanne structures three-dimensional form not by describing light and shadow, but by juxtaposing advancing warm hues with receding cool ones. Were also taught a good lesson in watercolorthat allowing veils of paint to dry before layering more color evokes color depth. The patches of untouched white ground that form an integral part of the pictures are something radical brought into his late oil paintings; they break the fourth wall (so to speak) of figurative painting by drawing attention to the picture plane itself.

None of this came easy. Czannes life was marked by terrible inner battle. He was by nature a recluse and couldnt bear to be physically touched. His laconic nature and Provenal background held him back socially, and he couldnt fit in with the hip Parisian artists to whom he was introduced by mile Zola, his friend from childhood. Many dismissed him as a sincere but clumsy artist who, though educated and able to read Virgil and Ovid in Latin, was a bit boorish. Lucky for Czanne, then, that his father, ended up giving him a monthly stipend and, finally, an inheritance that financed his outlier existence.

Czannes letters, which many artists like me have pored over, reveal a longing to convey his feelings in the presence of natureby which he meant conveying in paint the wholeness of the natural world. After abandoning Impressionisms fluffy formlessness, he spent the rest of his life drawing and painting nudes, bottles, apples, trees and mountains to balance his direct sensations with his inner knowledge.

Today, Czannes work often strikes the uninitiated as filled with errors and tentativeness. It takes hard looking and the help of a good teacher (in my case it was Professor Warren Maxfield, with whom I studied drawing as an undergraduate) to see that his mistakes are his plasticitypushing in here, popping out thereto try to get things right. For Czanne, to merely copy appearances was to lie. He tried to find a way to paint both the things and the space around those things, and on the way discovered that objects can be understood in painting only by looking at how they interact with one another.

One of Czannes most famous remarks is that he wanted to redo Poussin according to nature (refaire Poussin sur la nature). He aspired to Poussins classical stability, but without the academic baggage of perspective and chiaroscuro. To show the depth and roundness of nature, Czanne relied on the eye for the vision of nature and the brain for the logic of organized sensations. Or, put another way, the eye was to take in everything while imagination and reason decided how to structure it.

Czanne was filled with doubt that his search was leading to bad pictures, but he was no post-modern theorist thinking everything, including nature, is a social construct. What he doubted, and what is the thrilling and ultimately frightening subject of his art, was the possibility of ever knowing or understanding nature. Going through this exhibition I was reminded of why I love modern art. Art resulting from strong convictions shaped ahead of timereligious art, for examplecan be moving, yes, but remains locked into the function of an icon, an object for a viewers gaze. Art resulting from strugglemodern art, in particularasks the viewer to struggle alongside the artist. The viewer has to work to extract meaning from it. In exchange for that work, you are welcomed into a philosophical and aesthetic space in which you experience the freedom of figuring things out for yourself.

Czanne Drawing, Museum of Modern Art, 11 W. 53rd Street, New York, NY. Through September 25, 2021

About the author: Laurie Fendrich is a painter, writer, and professor emerita of fine arts at Hofstra University.

Related posts:

Fiction: The Square Drawing [Laurie Fendrich]

Fiction: The Teddy Bears [Laurie Fendrich]

Laurie Fendrich: How critical thinking sabotages painting

George Hofmann and Laurie Fendrich on artists writing, and the Duccio Fragments series

Thank you for this interesting analysis.

Thanks for this interesting analysis.

This is a spot on piece! There IS a pay off to such art that asks us to be there in empathy through the struggle. Thanks for the clear painter�s eye so well expressed.

Illuminating article Laurie Fendrich.

The author presents her hobbyhorse in the first paragraph. . While I agree with what she is attempting to say I do not agree with what she does say. Political or theoretical art is not inherently easy or bad. But if done poorly it is, certainly. Ad hominem generalities never lend themselves to constructive clear discussion.

Couldn�t one say Cezanne had a theory? A theory that made him the father of modern art.

I copied a still life of various objects, including drapes with patterns, and was awed by the organization and analysis of Cezanne’s drawing. Mine was a bit clumsy but a struggle with a favorable outcome,

Many Thanks.

Cezanne provided a fine example of lightness and solidity in painting when I was an undergraduate. I guess you can call him stalwart. I don’t think Cezanne was too bothered by labels because he was exploring areas of painting that hadn’t been explored before.

This wonderful essay reveals aspects of Cezanne still so important, and not only for artists. Cezanne’s struggle to see better, to see the whole of nature, to see past preconceptions- actuallly ‘gets him someplace,’ which we feel when we look. His hard-won seeing connects one more intimately to seeing, to the world. We usually live in an absurd state in which seeing is thought to give us no knowledge of the deeper aspects of the world-only science does that. But seeing, by Cezanne’s standards, does get you somewhere- new relations between light and solids, forms and forces, our insides and the world, challenging the impasse of alientation and absurdity.

I like the way the article focuses on just that – his pursuit. Cezanne’s proto-exploration of what would later be called Cubism is obvious in retrospect (arguably, a significant – if not THE significant brick in the mortar of modernist art history). The way in which the author adheres to a more experiential, pragmatic approach in digesting Cezanne can lead to deeper insights, such as the sense of discovery Cezanne must have felt in his endeavor.

A drawing by Cezanne conveys a sense of time. Every mark is another attempt to record what he saw at that moment and attests to more or less than that. For me therein lies the sense of freedom I feel with Cezanne along with his commitment and rigor. The color is luminous (unless we are looking at the early, dark, thick, awkward, almost angry oil paintings) and feels like a reward for the efforts of the line.

Wonderful insightful examination!

I hated Cezanne as a child for the same reason I love him now. He finds the deep structure in everything, even sky. Belated Thanks for the review!