Contributed by Sharon Butler / “Paul Feeley: The Shape of Things” is Garth Greenan Gallery’s fourth solo exhibition for the painter, who died in 1966. But it is the first to ask – and answer – what happened when Feeley, known for re-introducing geometry to post-war abstraction, grew tired of his signature style. This show at last gives proper attention to Feeley’s drive to move beyond the flatness of the canvases he had been producing for years. Other, similarly restless artists made different choices. Philip Guston, for instance, dramatically shifted from Abstract Expressionism to cartoonish figuration that confused collectors, critics and artists alike, but ultimately became an iconic and influential body of work. When Feeley reached this creative juncture, he must have envisioned his geometric forms, which he originally introduced to temper what he saw as the histrionics and theatricality of Abstract Expressionist paintings, bursting into three dimensions, holding space with viewers as if they, too, were humans. Even 60-plus years after the fact, the transition is fascinating to behold.

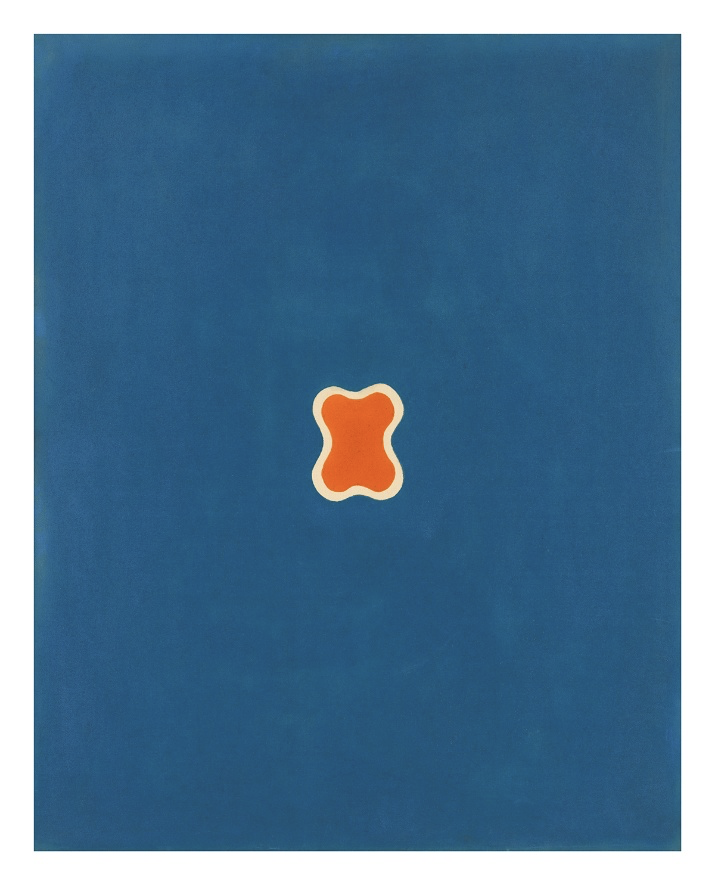

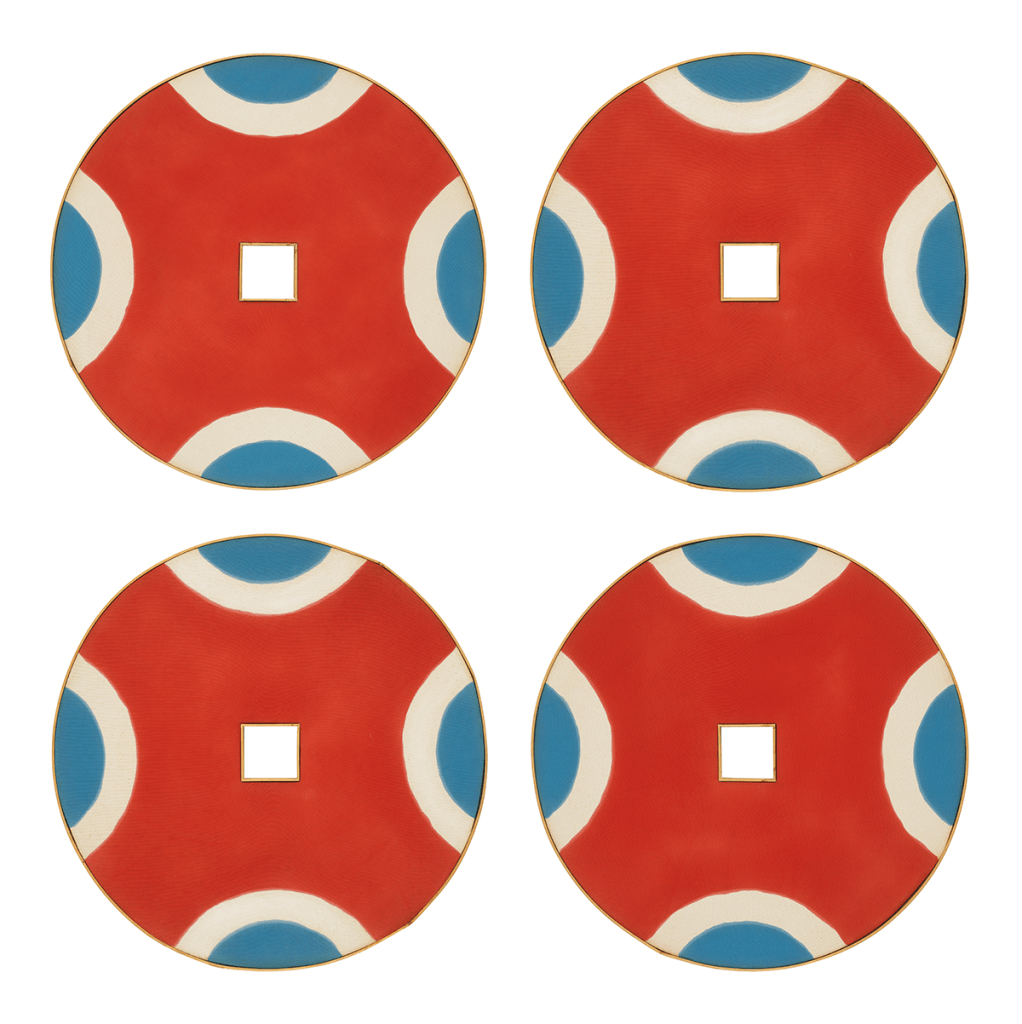

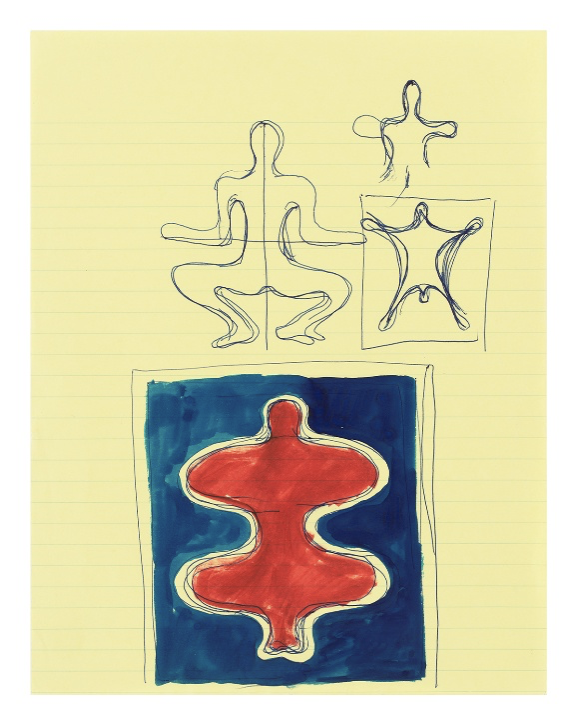

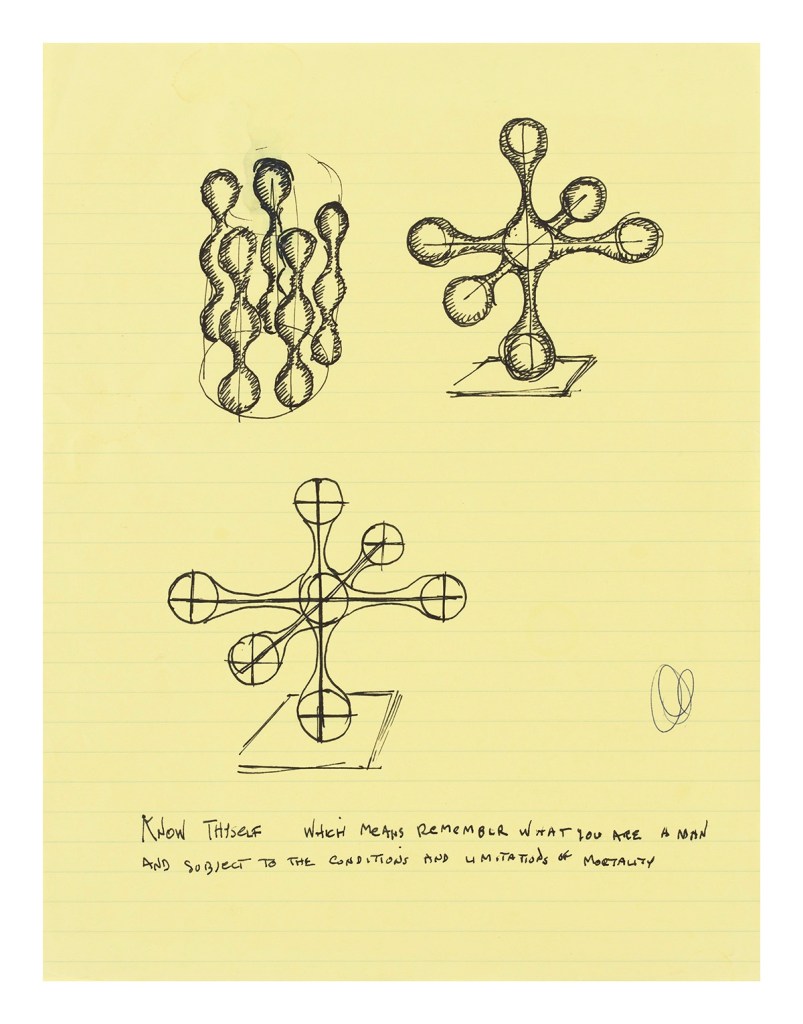

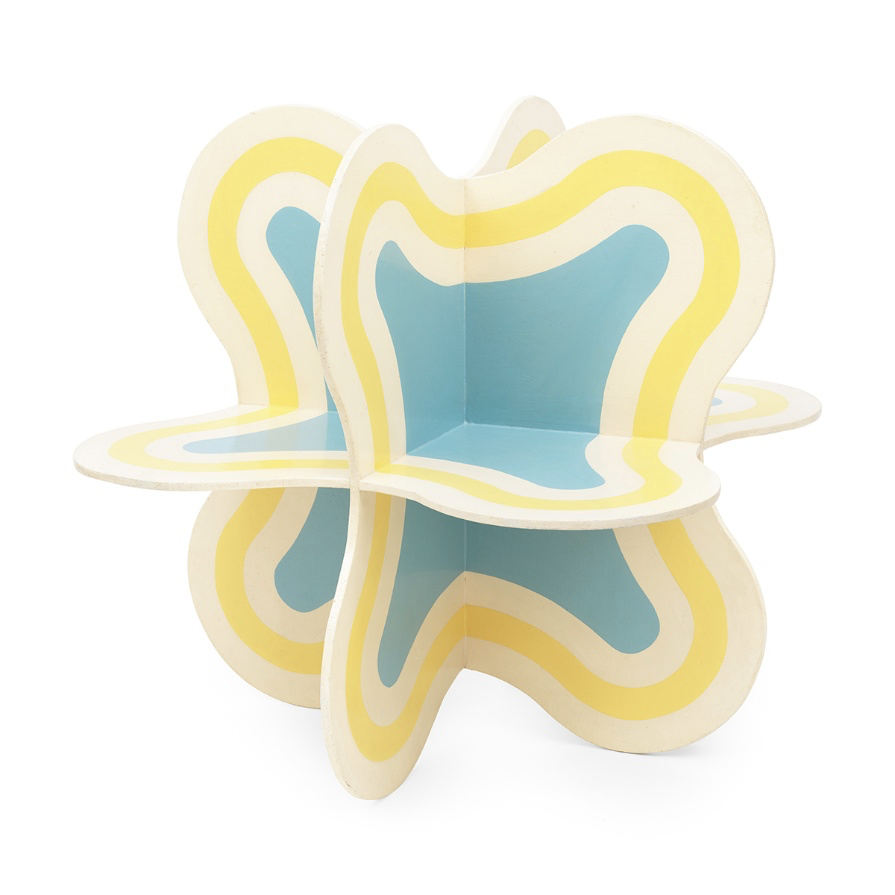

The exhibition includes, in addition to many of Feeley’s finished three-dimensional works, the preparatory materials – maquettes, sketches, and drawings – that show how Feeley’s mind moved between flat surfaces and solid forms and trace his process. Perhaps the most intriguing feature of the sculptures is that they, like IKEA furniture, are made from flat pieces that fit together at a very human scale. An early adopter of stain painting, in which the canvas is a site for process and experimentation, Feeley must have seen paintings as objects rather than images long before he turned the geometric shapes into sculpture. Several of his canvases have framed holes in the canvas, located at the center of the painting, hinting that he had tired of Hans Hoffman’s push-pull color theory and craved real, not illusionistic, space.

each canvas: 36 3/4 x 36 3/4 inches

Feeley’s jacks-like images from the early 1960s embodied unusual psychic energy for geometric painting, but were far more reserved than Abstract Expressionist paintings. He rendered the shapes with such clarity, often against white backgrounds, that liberating them from flat surfaces and building them out seems, in retrospect, inevitable. Though he utilized repetition strategies like a minimalist, he managed to imbue each form with a distinct personality. His work is usually discussed as an exploration of formal issues, but the handwritten notes on his sketches reveal that Feeley was angling for deeper meaning. One example: “Know thyself – which means remember what you are – a man and subject to the conditions and limitations of mortality.” Another sketch makes it clear that the jack shape evolved as a stylized version of a male figure. In this light, the lighter colors outlining the color-saturated shapes in the sculptures suggests radiant auras.

Now, as artists work freely across all mediums and platforms, the measured boundary-crossing that Feeley undertook in the 1960s may seem quaint. Still, there is something durably refreshing about his conviction, then iconoclastic, that undulating lines and shapes could convey a robust sense of humanity, and that even hard-edge geometric shapes could convey emotional content. Here, emphatically and winningly, he makes the case.

“Paul Feeley: The Shape of Things,” Garth Greenan Gallery, 545 West 20th Street, New York, NY. Through October 25, 2025.

About the author: Sharon Butler is a painter and the publisher of Two Coats of Paint.

Glad you researched the titles of the works and added notes! It definitely adds to my understanding. I’ve always loved his work even if not always been able to place it.

love this work, enjoyed the article’s content