The following transcript is an edited version of a conversation between painters David Humphrey and Gary Gissler that took place on October 3 at Anita Rogers Gallery. The discussion was held in conjunction with Gissler’s solo exhibition “against interpretation,” which was on view at the gallery from September 3 through October 8, 2025.

David Humphrey: I’m going to improvise this conversation, but I have a thought to start with that has to do with the title of your show, against interpretation. I want to think about each of those words separately and then spin it into a conversation. Let’s start with interpretation. I’m reminded of a famous quote from Nietzsche that’s been re-quoted 18,000 times: There are no facts, only interpretations. This turns out to have all kinds of interesting and pernicious reverberations as we navigate our post-fact politics. But also it had a life within deconstruction and opened up a way of thinking about thinking. Interpretation designates a very primary relation that spectators have with artworks. What do we do with them? What do they want from us? What is their sociability? Oftentimes an artwork solicits an interpretation. But here we have a show that’s against interpretation. I want to start by asking you what you think about interpretation and what associations you have with it.

Gary Gissler: Yeah. Interpretation. I didn’t actually lift it from Susan Sontag.

How we interpret our culture is based not just on seeing something and naming it, but how we recognize that we’re seeing it in a room, and the room informs the thing that we’re looking at. So that’s the baseline for me. I’m in private practice as a psychoanalyst. And in that practice, there’s also the story that we tell about our lives and the associations that we make and the burden that we’ve developed for it, and freedom from that comes from reinterpreting those circumstances that we tell a story about. I’ve taken that perspective and introduced it into my work and into my life. I’m really clear that there is no reality, that all there is is the words that we throw at something before naming it, and then we have this thing that’s real. One of the problems with language is that it’s clunky, it never really gets to the true essence of what something is.

DH: My understanding of Sontag’s argument in her essay Against Interpretation is that somehow language and criticism impedes or gets in the way of a primordial relationship with the object. I think this idea has a utopian dimension, but I think she is mostly making an argument against bad criticism, because good criticism establishes a living relationship with whatever the object is in the context of how one experiences it. Her argument against interpretation appears consistent with the kind of inclination you have to a primary encounter that can skid around language, while perhaps acknowledging its impossibility.

graphite on vellum, 12 x 12 inches

GG: Yeah. The thing is, though, we don’t, in the moment to moment of living our lives, recognize that we’re interpreting reality and that it’s not really possible to get there. We keep blundering into our lives thinking that this is the reality that we’re building a truth. I think the best we get is some description of what’s before you, like your checkered shirt.

DH: I like the idea that the brain uses a kind of anticipatory algorithm to summarize sense data and make our movement through the world more efficient, apparently fluid. If we saw everything, we would be overwhelmed and disoriented.

GG: That’s really good.

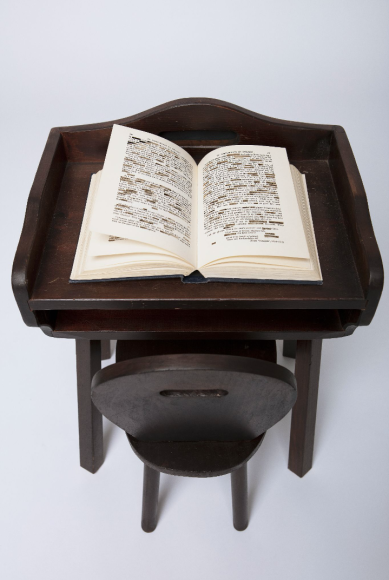

DH: Here’s my other thought about the word interpretation. You have a copy of Sigmund Freud’s book Interpretation of Dreams pinned high on the wall by a long rod attached to the floor. One of the things Freud gets at in that book is the idea that there’s a manifest content and a latent content in dreams. The manifest content is that I’m being chased or whatever – the subject matter of the dream. The latent content is the thing that free association and hopefully some interpretation can reveal. Perhaps your process of taking a text and burying it, making it unreadable, is a way to return that manifest content of the text, Moby Dick or Freud’s dream book let’s say, into a state of latency.

GG: I like that. And then the next obvious consideration is how many interpretations are there? Because there are endless. And which one do you pick? And similarly in life, that’s what we do. Pick the interpretation that’s going to be most empowering or engaging or self-serving. Which one’s going to make me the most money? Which one’s going to make me happy? Which one’s going to get me a partner? Which one’s going to make my dad love me? You know, it’s not a blithe intellectual inquiry. This is where we live our lives. And I take it seriously in both of my practices.

The embedded text is the last line from “Brave New World” and the poem from Gertude Stein “The Answer”

DH: I think it’s worth thinking about how your labor, your behavior produces these things as part of the subject matter. You perform a private act of reading and then bury it within incredibly exquisite surfaces. Your reading experience is entirely and dramatically occluded. Your work declares, “I did something and you can’t know about it”. And that to me has an interesting psychological dimension.

GG: I was just thinking about the nature of intimacy. When do we lower that veil? Are we even able to share that? I tell a story in the catalog for this show in which I was taking the subway out to Brooklyn and I’m standing over this woman who’s sitting there reading a well thumbed copy of War and Peace, a big ass book. She’s got like four pages to go. I’m standing and we’re riding and I’m watching her. And she finishes. I’m getting chills remembering it. She closed the book and I wanted to engage with her and say something. And to your point, there’s no way anything I could say that would interrupt this kind of ecstatic moment that she just had of completing this massive, intense novel.

DH: In a way, her face is the equivalent of your paintings. You cannot access the content of her experience. But you can project onto it of course.

GG: Yeah. And I know that when I project onto it, it would just be my interpretation. The stuff from my perspective, my reading of that book, where I was going and what time of day it was and was she cute. There is all this content that we’re constantly trying to make sense of and interpret so that we can move through life. And you know, oddly, language isn’t very good at that. But it’s the best thing we’ve got. It’s the most user-friendly thing we’ve got. Part of my practice is to undo the preciousness of that. Language doesn’t tell you what you need to know. Wake up. Use your words better.

Book: 8.5 x 5.75 inches

Adjectives and adverbs removed from text;

(these grammatical forms are the descriptors, the essence of interpretation, hence removing them removes the interpretation from the interpretation of dreams, leaving only the dreams…)

DH: The extent to which you are against words seems powerfully ambivalent. You bury them, you do violence to them, at the same time you fetishize them. Whether it’s a literally pulped version of Moby Dick or every word from Interpretation of Dreams or whatever, it’s a ritual that you’ve performed. And I guess that gets me to the first word of the title of your show, Against. To have this show be Against. That’s interesting because it’s sort of implies…

GG: That I’m saying no, like I’m down on interpretation.

DH: Right, like Susan Sontag.

GG: Yeah, but as you said too, with Sontag, it’s not like I’m against it, it just should be better.

DH: I see these works as aggregations of different kinds of labor. There’s the labor of cutting and reading, which is private, writing over, erasing, more or less obliterating. And then there’s the incredibly careful articulation of surface. These grounds, let’s call them, are some of the most exquisitely articulated objects out there. You obviously have spent a huge number of love hours that resonate with the other labor of burying the text. This is what I’m calling the ambivalence of saying “I’ve made this beautiful thing for you to look at, but I’m going to withhold an important part of it. That’s the interpersonal challenge that you’ve created. This is part of the “against” dimension that to me is psychologically interesting.

GG: Betwixt is a new word for me that I’ve really been loving. It’s like when you come to a fork in the road, you can dwell there or you can pick a way to go. And that kind of Mythological moment always infers that now you’re on that path.

DD: I thought you were going to say something really rad like you go down both paths at the same time. You perform a kind of quantum entanglement.

GG: No, actually, you can go down that path. And at the same time, when you’re going down the path, you’re wondering what’s on that other path. And usually what we don’t do is turn around and come back and go down the other path. You don’t quit your job and go back and become a car racer.

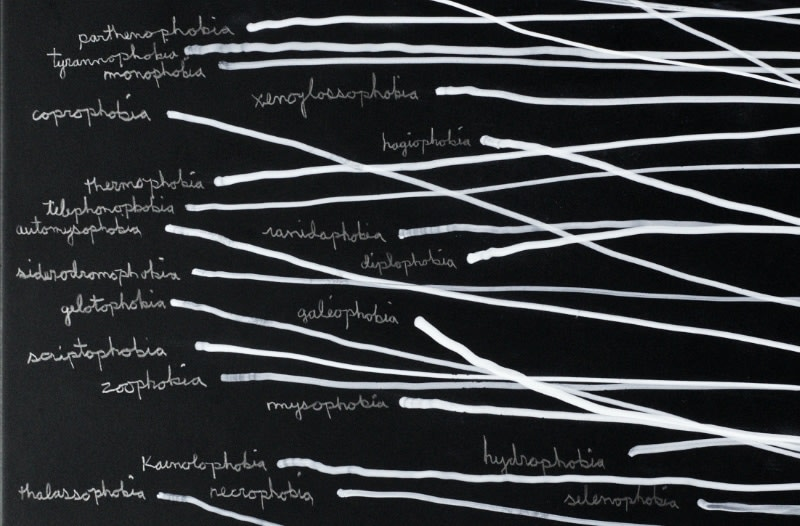

The left panel holds a definitive list of clinical phobias (detail above), the right panel lists the fears themselves.

DH: I don’t know how you define neuroses, but I think neuroses is a kind of a self-disabling behavior in which you go down one path and then realize you should have gone down the other, but maybe I should have gone down the first one. And so, in fact, you’re never on either path.

But also, appealing to your double life as a psychotherapist and an artist, I’m thinking of the dyad, the conversation, as we understand it in therapy, that includes the dimension of transference and counter transference. Your radical listening, your crafted passivity, has a kind of structural resemblance to the charged relationship of spectator to the artist. I’m thinking out loud.

GG: I’m thinking with you. In communication theory there is the notion that all the authority in a communication is in the listening, not in the speaking. You can be articulate or violent, but if the person’s not listening to you, there’s no communication. So in an analytic perspective, if you’re trying to say something to your partner, you have to set up the listening and then you can speak into that. That’s a good tip. So as I’m sitting here now thinking about, as artists, how do we set up a listening? But this work that I do is not in vogue. It’s like the listening isn’t set up in the culture right now for my type of artwork; it’s big colorful paintings. Can an artist actually mold how someone listens?

DH: I wouldn’t take these works as being not in the moment. It seems like there’s a mindfulness ethos that has saturated so much of the culture: slow eating, deep listening, meditation. I feel like your work exhorts or solicits a very slow and mindful looking that so much depends on the nuance of surface, a little smudge here or an erasure there.

GG: Yeah, good, thanks. We’ve been moving towards Buddha nature since the 60s and there’s been a resurgence of mindfulness meditation over the last 15 years or so. So this is clearly consistent with that. I was just referencing the art culture in general. Spare work is not coveted right now.

DH: I would say these works are probably not very Instagramable. So maybe in that sense you’re right.

GG: But the details can be very satisfying to see.

DH: Museums are putting out incredible high-res images in which you can practically go all the way down to the molecular scale.

The left panel holds a definitive list of clinical phobias, the right panel lists the fears themselves.

GG: This work is very meditative. In 1969, when I was 14 years old, my friend Leo Jones and I decided that we were going to start doing transcendental meditation. Maharishi was here, was working with The Beatles, and that was cool. So we were going to do this cool thing and started meditating. I’ve had this awareness and a practice for 50 plus years and it’s part of my life.

DH: I feel like it intersects with and has some connection to psychedelic culture, which is a segue to talk about the drawings you did while tripping. It resonates with the other works to the extent that it feels there’s a component to it in which you had an experience, cutting, looking, reading, tripping that we have no access to. But here is the evidence. So what is it that you hope people will get out of your drawing under the influence.

GG: That’s such a hard question. Jesus. I mean why do we make art? It’s like you’re compelled to do it. You start doing it, you keep doing it. But there’s something about wanting to. Our culture has become so high paced with fast images, and we’re intolerant of a deep consideration of anything that we’re flashing past. To engage with this work demands that you slow down and get up close so that you can almost hear your heartbeat. You can feel your breath come back off the artwork. To be drawn in by something that’s got a sexy surface is part of the strategy. It’s like, that’s really cool; let me go lick that thing. And you get up there, and there’s more content and you’re compelled to slow down. That’s one answer.

DH: Maybe I’m being the annoying critic Sontag complains about who wants to put language onto it. Your work is not like Aldous Huxley’s Doors of Perception that describes the psychedelic experience. It’’s more like Henri Michaux’s drawings, which testify to having entered into this state; his work is a byproduct of that state. Maybe your drawings hide the particulars of your personal experience in order to become a new thing that is both you and not you.

GG: Michaux did those drawings on psilocybin. That show at the drawing center was mind blowing.

DH: In my psychedelic experience tripping got in the way of working. The synthetic imagination, the glory of associations unfolding in real time couldn’t be captured. I was too disorganized and immersed in the swamp of expanded consciousness.

GG:That’s fair. And I should articulate two things. One is that I realized I can’t not do this, explore it and find my own healing.

DH: As a clinician.

GG: Yeah, as a clinician. And I did, and it’s breathtaking. This work is very thoughtful; it’s a concept, very idea driven. The blabbering in my mind is going on all the time and there’s a kind of madness there. In the psychedelic work, clinically, there’s a thing in the brain called the default mode network. The default mode, is where we have our stories, our interpretations: I was born here: i’m this color, I’m this gender, these are my parents. It’s a story. We live our lives as though that’s the truth. It’s a burden or it’s a joy. Psychedelics takes that offline so that you’re just dwelling in an immaculate sense of clean consciousness. Your heart experiences what it’s like to be free of this story that has become a burden. You have a somatic experience of what it’s like to be free of that. You emerge from the experience to do your work and hopefully grow with more freedom in your life. When I was doing these drawings I found doses that were just enough to take the default mode network offline but not make the walls melt. I’m in a betwixt state with language disabled. I’m not trying to make a drawing. They just came out without intention.

DH: I guess that’s the effect of what they call ego annihilation. But it sounds like you didn’t go all the way to annihilation. You went maybe to erosion.

GG: But what’s that, a quieting?

DH: If the ego is founded on the narrative that one constructs about who we are, then taking psychedelics could be a very progressive and potentially restorative procedure. Maybe your paintings, in their oscillation between secrecy and suave beauty, are performing a version of that process.

GG: We want to be suave and stylish and also have an openness to not jumping to conclusions about who we are, what life is, or who’s in the White House.

“Gary Gissler: against interpretation,” Anita Rogers Gallery, 494 Greenwich Street, Ground Floor, New York, NY / September 3 through October 8, 2025

About the author: David Humphrey has been the subject of 44 solo exhibitions including McKee Gallery, NY; Sikkema Jenkins, NY; Fredric Snitzer Gallery, Miami; and Contemporary Art Center, Cincinnati. His work is in the collections of several museums and public collections including Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY. He was awarded the Rome Prize in 2008. Humphrey has had five solo exhibitions at Fredericks & Freiser in New York City. He teaches in the MFA program at Columbia.