Contributed by Jacob Patrick Brooks / I often want to touch paintings when I go to galleries, but I rarely do. I know I can get away with it, but it doesn’t usually seem worth the risk. What new phenomena could I possibly discover after years of making art? It’s a depressing thought, but one I’m mercifully relieved of when I see a Pol Morton piece. “Get Well,” their solo show at Olympia, is a trove of stuff you want to lay hands on and dig through. I could write a novel going through all the materials. In the interest of brevity, I’ll stick to how it feels to look.

Morton’s work is sensual, exploring touch in many ways. The surfaces are chaotic – cacophonies of materials in which paint, often scraped on, serves as a structural base for a bricolage of beads, sequined bruises, and hospital items. Care, in numerous forms, is a central theme. Get Well, the title painting, hangs outside in a shallow, street-level window space. It’s both an invitation and a request to feel better. A metallic balloon is cut into two hearts that rest in the center of the work. The surface is smeared with red paint and a grid of dots, resembling an allergy panel. Below the hearts are handmade sequined feet with shimmering bruises and scars. A pair of hands, also handmade with sequins, is at the top of the rectangle. The painstaking attention needed to put these silhouettes together underlines the care implied by the balloons.

Exam Shorts, Blue Large is more collage than painting. But strips of paint improbably knit its disparate elements into a cohesive whole. This gives the piece a diagrammatic feel not unlike a public transit map. Garments zig-zag up the surface. starting with the titular blue exam shorts hanging upside down. Above and slightly to the right is a pair of tie-dyed underwear, right side up. It sits between a tubular bag made of thick, flexible plastic and a photograph of someone wearing the underwear, upside down. (This upside-down/right-side-up motif is repeated throughout the show, notably in Accident 1 and Accident 2, two oversized helmets that live on the floor.) Images proliferate on the surfaces – a hole in a tree stuffed with pinecones, a mysterious blue drink in triplicate on the left border — but feet pics dominate. About eight of feet in various states of healing and trauma populate the lower right quadrant. Carefully chosen and evidently autobiographical, the cluster of images – a bandaged foot, a purple leg next to a normally colored one, a hospital poster of a leg – tell a nonlinear story about healing and care. Especially compelling is the depiction of someone washing a wound as yellow suds accumulate around the brush and hand. At the top of the canvas is a person’s frowning face, establishing that what they’re going through sucks. It’s touching, hilarious, and utterly relatable.

15 x 17 x 22 in (38.1 x 43.2 x 55.9 cm)

Cane/Can again employs collage with a dusting of paint. Here Morton’s organizing theme is a compass of cane outlines, carefully traced in graphite. The spider-webby character of the handles creates a pleasant density at the center. Colorful lines radiate from this core. Sometimes they consist of paint, but they also include sequins, beads, or bicycle reflectors. Between these lines are photographs cut into footprint shapes. The one photo that doesn’t conform to this pattern is also the only actual photo of a foot, covered in cobalt blue paint and stamped onto a drop cloth à la Yves Klein. It’s an elegant way to substantiate footprints with a reference to flesh and blood.

Morton’s photos convey a sense that everything is meaningful and, more importantly, useful. Whereas Exam Shorts is iconographic, the images in Cane/Can are linked by a less visually clear but still poignant emotional logic. It’s like an exploded photo album, spewing forth checkerboards, office buildings, walk/stop signs, a rainbow on a wall with a light dimmer., beautiful flowers, and a fence. The images evoke familiar places and imply movement; there’s a subway map and big sloshy steps in freshly poured concrete. In this context, the use of canes as icons and organizing mechanisms is significant. Mobility tends to be taken for granted until it is constrained. The footprint also carries weight. The sole of the foot is extremely sensitive, so stepping on something suggests connection. Casual snapshots of foot-shaped images seem to hold deep significance for Morton.

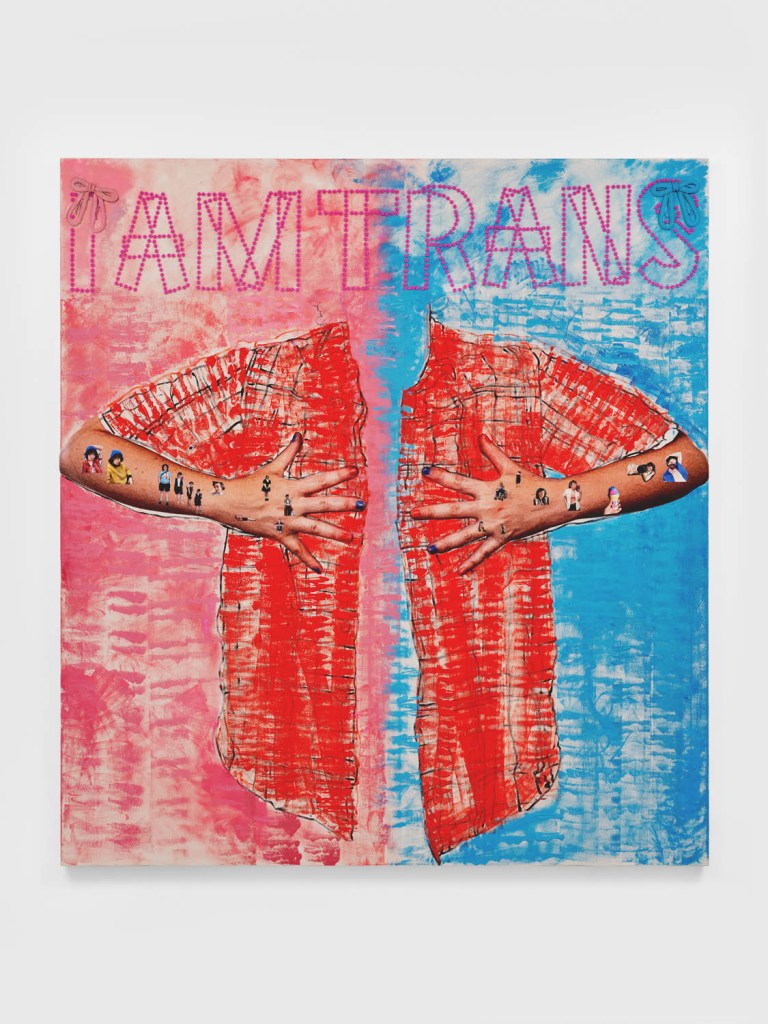

My favorite work in the show is Iamtrans, charming in its in-your-faceness. The title is written across the top of the rectangle in block letters composed of pink-bow beads. Pink paint is scraped on the left side of the canvas with a dry brush, blue paint on the right side. Occupying the middle of the canvas is a loose grid in the form of a red plaid button-up shirt, open to reveal where the colors meet. Photographs of arms and hands emerge from the armholes, fingers spread as if pressing flesh to confirm a body exists. Self-conscious self-portraits spread over these arms like scabs. Think Instagram, not Cindy Sherman. This work is exceptional for its boldness, and because it is the only piece in a clearly autobiographical exhibition that shows the artist’s face. With the propagation of selfies, Morton might be seeking to assure us that the artist does, in fact, exist – that an actual person experienced the pain and care depicted elsewhere.

72 x 66 x 1.5 in (182.9 x 167.6 x 3.8 cm)

Each piece in the show is a jumbled, tangled thing, barely a painting and definitely not a sculpture. Maybe something in between. Who knows or cares? The work is beyond the fussy categorizations of the art market and academia. Morton delivers a mess in the best way, exploring the meat and potatoes of specific experience without straying too far into narrative or losing sight of technique and formal concerns. All bodies are in pieces, every surface is sensitive. Instead of telling us how something hurt so bad or felt so good, they invite us to process with them, to feel the life we see in the work. It evokes a tip-of-the-tongue kind of feeling, endlessly exhilarating and frustrating. We’re urged to accept that there are no real answers, just feelings and events to sift through.

“Pol Morton: Get Well,” Olympia, 41 Orchard Street, New York, NY. Through October 5, 2024.

About the author: Jacob Patrick Brooks is an artist and writer from Kansas living in New York.