23 7/8 x 31 1/2 x 4 1/4 inches (60.6 x 80 x 10.8 cm)

Contributed by Joe Fyfe / A souvenir booklet accompanied Leonard Cohen’s “I’m Your Man” tour in the late 1980s. Among assorted photographs and reproductions of his sketches, was a thousand-word essay, “How To Speak Poetry” that has had a second life on the internet. In this singular artistic manifesto, Cohen admonishes singers that they are “among the people. Then be modest. Speak the words, convey the data, step aside.” On the next page, he tells them to “think of the words as science, not as art. They are a report.” If an audience appreciates the event, “it will be in the data and the quiet organization of your presence.” Su-Mei Tse’s current exhibition at Peter Blum Gallery seems to freshly embody Cohen’s abiding concern with presentation and how an artist must address an audience.

51 1/8 x 11 3/4 x 11 3/4 inches (129.9 x 29.8 x 29.8 cm)

Tse works with found textures from the natural world, as well as fabricated objects, plinths and vitrines, printed photographic imagery, sound, bodily movement and performance, and sculpture- often in combination. About her subject matter she is willing to use the term “spiritual.” In Cohen’s vocabulary, her works might be thought of as spiritual reports. They don’t overwhelm as events so much as they allow access to a continually examined life. She often selects naturally occurring phenomena that she frames within cultural, historical, mythical, philosophical, or literary narratives. This involves finding a form in which to set existential preoccupations amidst everyday experience or reflections on the classical world.

A good example here is a photograph of the Aegean Sea, taken after an arduous hike, from the tip of the Peloponnese, the southernmost point in continental Europe. The End of the World, a recurrent title, looks out at the waters and away from the entrance to the mythical Gates of Hades, the ancient Greek underworld. The dark waves that take up more than three-quarters of the frame recede towards a vague whitish horizon. The image is about the size of one of Caspar David Friedrich’s larger paintings and alludes to his work as well. The sea here, though seen from the mouth of death, is also like death: deep, opaque, general. Tse steps aside and the soul (or simply the viewer) departs into reality for unknown shores and consequently away from myth.

47 3/8 x 92 3/4 inches (120.3 x 235.6 cm), overall, edition of 5

Japanese Garden (Kanazawa) depicts a landscape of trees whose long, horizontally grown branches are held up by wooden poles in one of Japan’s oldest gardens, growing since feudal times and considered to be among the country’s most beautiful. Part of its traditional maintenance, the stilts hold up the tree branches during heavy snows. This innovation echoes one of Tse’s ways of working in providing a support for an object found in nature. Others do, too. Meltemi (Aegean Winds) is a delicate gathering of pine needles bundled by the wind into a cushiony oblong gift that has been placed inside a vitrine on an antique table. Tse found the needles during a walk on a Greek island. The title is the name for the dry Aegean winds, harsh and unpredictable, that come down from the Bosporus.

26 3/4 x 19 5/8 x 13 3/4 inches (67.9 x 49.8 x 34.9 cm), overall

Tse was trained as a classical cellist, and there is a calm precision in everything she does over a diverse range of materials and approaches. She seems both a composer and orchestrator. There are interconnections across mediums in her works, texts, and titles. Though each work on display here is autonomous, there are associations and visual rhymes among them, leading to larger themes, such as that of the world as a single organism. Several spheres appear, for example, one in the form of a large image of the far side of the moon in an eponymous photograph. On the floor nearby, Dorodango (big) is a sphere, the title referring to the Japanese craft that teaches the patience and delicacy of shaping perfect three-dimensional rounds from mud. God sleeps in stone is a smaller ball made from earth with cracks running through it, sitting on a white pedestal alongside the mystical Sufi quote “God sleeps in stone, breathes in plants, dreams in animals and awakens in man” on the adjacent wall in ribboned metal lettering.

21 3/4 x 35 3/8 x 35 3/8 inches (55.2 x 89.9 x 89.9 cm), overall

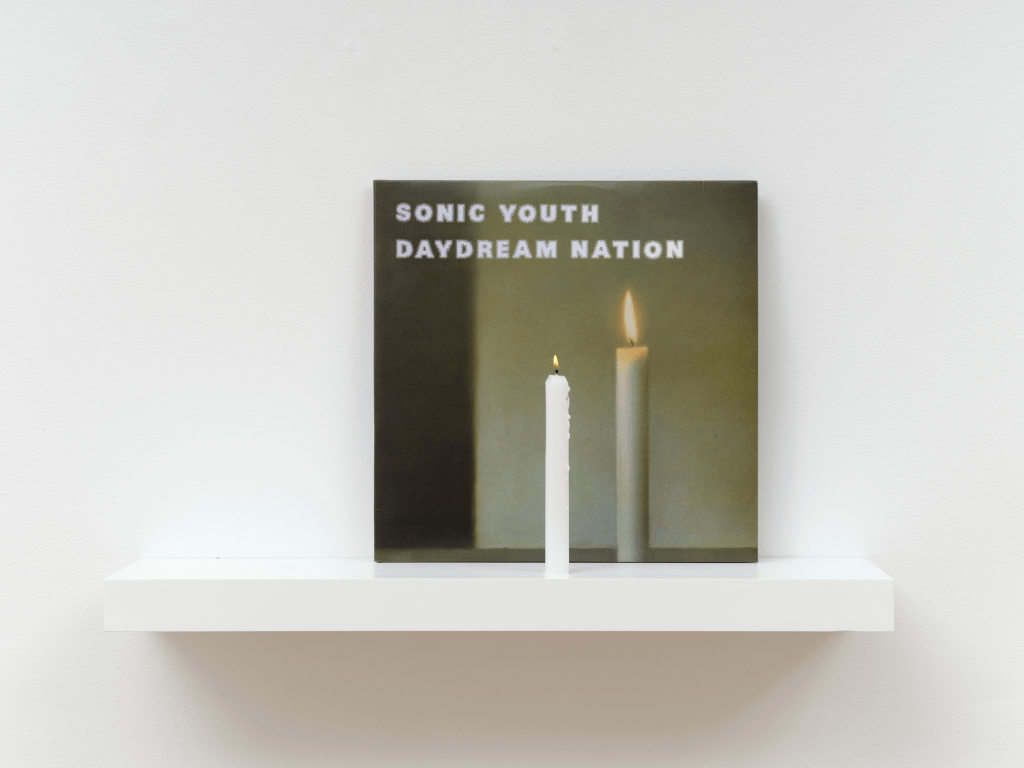

There is evidence of music throughout. The photograph Bird Song depicts white birds against a night sky, all perched on electric cables that stretch diagonally through the frame, reminiscent of notes on a staff. Daydreams evokes a moment between the dazed and the contemplative via a waist-high shelf holding the jacket of Sonic Youth’s LP Daydream Nation with its reproduction of Gerhard Richter’s painting of a candle, with a lit candle that Tse has placed in front of it.

27 3/4 x 36 5/8 inches (70.5 x 93 cm), framed

14 1/8 x 24 x 6 1/2 inches (35.9 x 61 x 16.5 cm), edition of 30

87 x 129 x 38 inches (221 x 327.7 x 96.5 cm), overall

The title “This is (not) a Love song” is from a Public Image Limited tune, and it has to do with all that is not being said in her work, as she is apophatic. Apophatic theology, originating in ancient Greece, is about the impossibility of knowing God and focuses on what cannot be said about Him. God Sleeps in Stone, the cracked ball of dirt on the pedestal, might well be intended to negate the quote that accompanies it. Leavening Tse’s enigmatic musings are her acute attention to detail and her willingness to enact a formal engagement with the viewer

“Su-Mei Tse: This is (not) a Love Song”, Peter Blum Gallery, 176 Grand Street, Floor 2, New York, NY. Through January 24, 2026.

About the author: Joe Fyfe is a New York City-based painter who also writes. He recently participated in the exhibition “Regarding Kimber” at Cheim & Read and had work in the group exhibition “The Shape of Color” at Peter Blum Gallery. He received the Rabkin Prize for visual arts journalism in 2022 and is currently working on a biography of the artist and critic John Coplans. He is a contributing editor at BOMB.

Go Joe! Love the East/West reading.