Contributed by Jacob Patrick Brooks / In “The Art Critics Who Don’t Want Good Art,” Anna Gregor describes a cultural hospice. The caretakers are a set of bad actors. They’re online critics who have replaced the labor of criticism with the catharsis of complaint, trading in “likes and clicks” for a smooth, sugary candy that requires only passivity and attention from its audience while it rots their teeth. This feedback loop, she argues, drowns true engagement and criticism in a “deluge of mediocre art.” It is a compelling diagnosis, but one delivered from the one place a critic cannot afford to be: behind a veil. Gregor deals exclusively in archetypes and generalizations while allowing the reader to “fill in the picture.” The playboi, the intellectualist, the yelper, and so on. She’s built a perfect haunted house and populated it with ghosts of her own making.

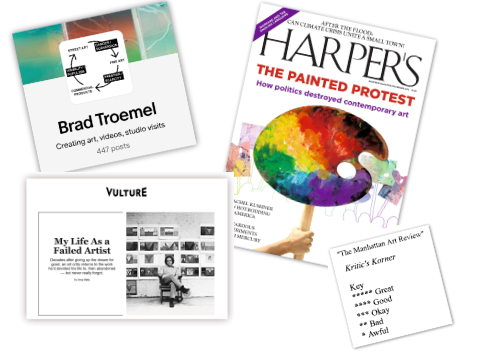

I will fill in the blanks she refuses to. The “anti-intellectual party boi” is Dean Kissick. The “Yelp-style blurbs” belong to Sean Tatol of the Manhattan Art Review. The lefty philosopher-parroting YouTuber is Brad Troemel. The failed artist turned critic is Jerry Saltz. Gregor’s fundamental error is to diagnose their behavior as a lack of commitment. It is not. It is a precise and logical adaptation to a system that has rendered her kind of commitment, the kind that dreams of Greenberg and his systems of judgement and close readings of Guston, obsolete. Kissick, Tatol, and Troemel are not the cause of the crisis; they are its most accurate cartographers. Their maps are legible only to those already lost in the same hell. They are mapping the contours of a collapsed ecosystem, a world where the market validates art and algorithms reward the very acquiescence she despises. This is a classic case of hating the player and not the game. They are not failing to be old-fashioned critics; they are succeeding as new fashioned content producers. In understanding that difference lies the real diagnosis.

The system Gregor proposes is not just nostalgic, it’s an impossibility. The 20th-century machinery of art, criticism, and culture has been stripped for parts. Its value is determined by auctions and collectors, not critics. In this marketplace, criticism is not an indicator of value but a generator of content, a secondary industry feeding on a primary one that no longer requires its seal of approval. This is the collapsed ecosystem that Kissick and Tatol are mapping. To criticize them for mapping is to criticize a cartographer for not being a conquistador. The territory, and the entire purpose of the exploration, has fundamentally changed. Faced with this reality, critics tend towards two poles: become another content producer for the machine, or find a way to break its logic entirely.

The art world we want to exist in is no longer feasible. It’s been so thoroughly infected by the parasite that is the artmarket, it must be abandoned as a central site of value production, its logic subverted by building new, parallel economies of meaning on its periphery. The good news is that this collapsing system contains the seeds of its own irrelevance. The map is not the territory, and the cartographers of collapse are still trapped within its logic. What comes next cannot be another map. It must be a refusal to use the old coordinates altogether. If value is determined by the market and engagement by the algorithm, then the only critical act left is to systematically refuse their terms. This is not a retreat into philosophy; it is a tactical counterstrike. In Psychopolitics, Byung-Chul Han calls this “idiotism”: the strategic embrace of the idiosyncratic to block the “unbounded communication” of the market. The idiot does not play the game better; they invent a new one on different ground. We must deny the logic of the game that’s dominated the last half century. This requires forms of expression that deny the individual and the market: anonymous collectives, criticism written as fiction, a deliberate embrace of obscurity that algorithms cannot parse. The form itself must be the first act of criticism.

Do not mistake my call for new games as a nostalgic plea for a new avante-garde, with its worn-out fantasies of shock, rupture, and eventual assimilation. What I envision is not a rejection of aesthetics or a modernist permanent revolution, but a wholesale expansion of expression and thought that cannot be transformed into commodities.

Could this be or mean a life in art in a more complex and intimate way, or rather ways? Could this mean a life in art as an infinity of options personified in the embodiment of multiple visions of a gazillion artists? Could this mean freedom to explore these ways of being and doing expanded?

A great relief of art is that it goes beyond the bounds of personal identity…………

What is true? That art is a spiritual practice making perceptions of reality clear and deep which obligates artists so privileged to speak truth.

Social engagement, street art, performative work? I was just visiting with a local artist here in Portland, Maine, Abbeth Russell, who is part of Hidden Ladder Collective, a group of artists, educators, painters, sculptors, makers, and musicians who have been doing great work for years around the country, getting little to no attention. Love that you are speaking for and reminding us about those who do not fit neatly in the commercial algorithm. There are many art worlds.

I don’t buy that Gregor was shading Tatol in her essay (and FWIW, I also doubt she spends a second thinking about Jerry Saltz). Much of Gregor’s critique is echoed in Tatol’s (admittedly petulant and long-winded) essay “Cornering the Critics”, where he rails against Kissick, Divacorp, and Scorned by Muses. IMO, what Tatol does, and what Gregor is calling for, both constitute valid and fruitful engagement with contemporary art. Tatol does tend to talk “around art,” as Gregor puts it, rather than going into depth on the formal qualities of specific artworks. But I think this approach is often very well-suited for probing the way that art fits into our contemporary context — for example, his analyses of the legacy of conceptual art in reviews of Joseph Kosuth or Stanley Brouwn. I tend to find criticism grounded in close reading to be a bit dry, but to shrug it off as nostalgic, as Brooks does here, seems overly defeatist (especially coming from someone who has written criticism himself). John Yau does close readings in a poetic way that can’t be reduced to applying formalist systems of judgment. I’m sure Yau would bristle at being called a Greenberg disciple. And I even enjoy reading Troy Sherman’s substack “A Critical Archive of Visual Art” (and Sherman would maybe self-identify as a Greenbergian), because I know his critiques need not be taken at face value; the point of criticism isn’t for the reader to be taught whether or not an artwork is good, but to see how different artworks are situated in the mind of a critic. Whether or not someone enjoys this kind of reading is another issue altogether — it’s perfectly fine to not enjoy reading criticism.

I second Gail’s comment above, that there are many artworlds. Most artists are already working outside of the market and algorithms, with no hope of making money off their work or ever having a review written about them. If one really wants to see art that exists off the grid, it’s just a matter of looking past instagram, past the art fairs, maybe outside of NYC. Brooks’ apparent contention, that all sense of value is so irremediably dictated by the art market and auctions, that it’s not worth even trying to engage critically with work exhibited in conventional galleries, seems to me extremely fatalistic, and strange given that he’s written several reviews of gallery shows for this very blog. His call for “idiotism” feels like a kind of performative disenchantment, not so different from Kissick’s desire for shock and awe — their critiques point in opposite directions, but neither offer much in the way of practical insight.

Agree with Jim, above. Have been thinking about the lack of audience (besides artists themselves) and dearth of criticism for a while, and my only answer is for artists to take these tasks on themselves. And they are. I have been seeing inklings of new communities creating places to show, artists writing about art (see Two Coats!)

and making serious work in the face of a frivolous culture. Who knows, things may change, as they usually do. What is the saying ? Ars longa, vita brevis.

I’d rather see us stick to our real involvement in work, despite the algorithim, rather than trying so hard to stay away.