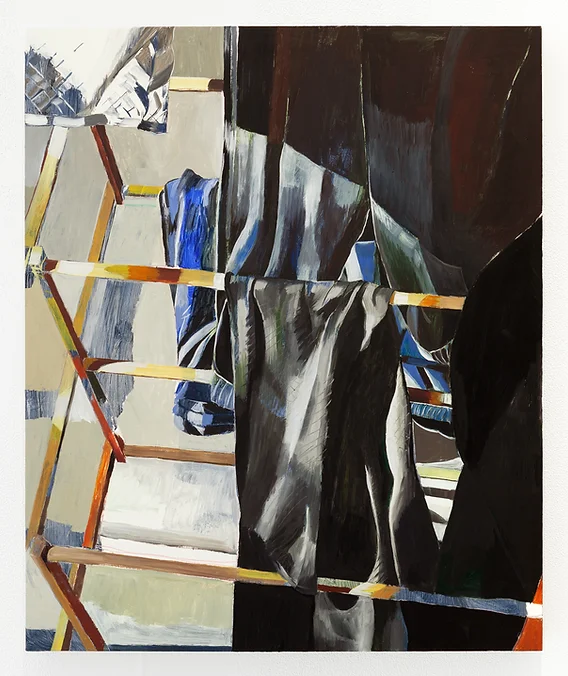

Contributed by Mark Wethli / Jay Stern’s paintings of domestic interiors and landscapes, now on view in his solo exhibition at Grant Wahlquist Gallery in Portland, Maine, invite us into familiar worlds but take us there in unexpected ways. The first time I saw his work – a series of paintings of a wooden drying rack – I admired how he transformed this humble, intimate household object into something iconic and worthy of attention. On a formal level, I was impressed by how the diamond pattern of the rack’s design served as a strong compositional framework, not unlike a trellis for an array of color patches whose abstract shapes, painterly shorthand, and understated yet luminous tonalities amplify our sense of the paintings’ warmth, intimacy, and human connection.

Shortly after Leo Stein, the American expatriate and art collector, acquired Matisse’s Woman with a Hat in 1905, his sister, Gertrude Stein, was showing it to a friend in their Paris apartment. As they were looking at the painting, her housekeeper happened by and remarked, disdainfully, “Look what he’s done to that beautiful woman,” upon which Stein commented to her friend, “Notice she said beautiful woman.” This anecdote sums up not only how modern painters introduced new means of representation but also how viewers innately, if unwittingly, adapted to them. Walter Murch, Jr., in his illuminating book In the Blink of an Eye, makes a similar observation about how readily and surprisingly the first film audiences accepted film editing, with its sudden cuts between scenes and camera angles. They might well have spurned these effects as too jarring, yet they found them both coherent and mesmerizing.

Jay Stern’s paintings employ a comparably disruptive visual language to similar effect. Composed of fragments of lapidary color reminiscent of stained glass, tile work, or frames in a film, they draw our attention to the mechanics of the painting even as they convince us of its veracity. This conscious process of visual interpretation energizes the act of seeing and activates our connection to the paintings’ meaning and content.

Stern’s sun-dappled interiors — rich with idiosyncratic objects and telling details, tantamount to ersatz portraits of their occupants — are quietly dazzling to the eye. Their dramatic contrasts of light and color bring to mind a daylight version of film noir: visually seductive patterns of light and dark with a tinge of mystery. While the paintings are devoid of visible figures, their presence is strongly implied, not least by our self-awareness as onlookers. Stern’s paintings give us, like house-sitters without fear of being noticed, permission to explore this environment freely and voyeuristically, gathering clues about its occupants, their lives, and their loves.

An exception to the absent figure is Forever Suspended in a Doorway (Self Portrait), in which a schematic self-portrait, reflected in a mirror, appears in the center panel even as its ghostly or provisional quality also suggests absence. Just underneath it is another fragmentary figurative element, the curious image of three hands resting on a stove top. Below this is what appears to be a dishtowel hanging on an oven handle, though it might also be the cropped midsection of a partial figure, dressed in jeans similar in color to the blues on the shirt cuffs just above it. If so, this spectral figure, standing at the stove, would align perfectly with the portrait in the mirror, completing this fragmentary apparition subtly but convincingly.

The repeated right hand in the mysterious group of three — reminiscent of the disembodied hands in Fra Angelico’s The Mocking of Christ – also presses the question of simultaneous realities and overlapping timelines while also imparting a symbolic, ritualistic, and metaphysical aura to the painting; an effect underscored by its tripartite, altarpiece-like format. Seen through a different lens, the compartmentalized bulletin board structure of the composition; the various types, tropes, and ambiguities of representation; the pictures within pictures; the perspective games; and Stern’s clear delight in the painting’s tessellated facture could also prompt comparisons to an artist as different as Jasper Johns. Like Johns’ work, as well as many of Stern’s other paintings, Forever Suspended in a Doorway (Self Portrait) presents an array of visual puzzles that both tease and reward the inquisitive viewer.

The element of time can be found in Stern’s other paintings as well. In Early Summer, he captures the effect of looking downward at the objects in the foreground and then fluidly tilting upward into the distance, suggesting a temporal movement as well as a spatial one. The half-eaten (and beautifully painted) watermelon in the foreground suggests that someone has just left the scene, providing yet another time code. As the eye travels up the canvas, a barn-like structure appears in the distance. Its proportions and stately bearing – as well as elements of its color, brushwork, and simplification –recall Matisse’s views of Notre Dame, which were painted through a window at a similar angle. There are also similarities in this painting – entirely coincidental – to Matisse’s other interiors, such as Studio with Goldfish, which likewise move with ease, in a variegated light, between different points of view.

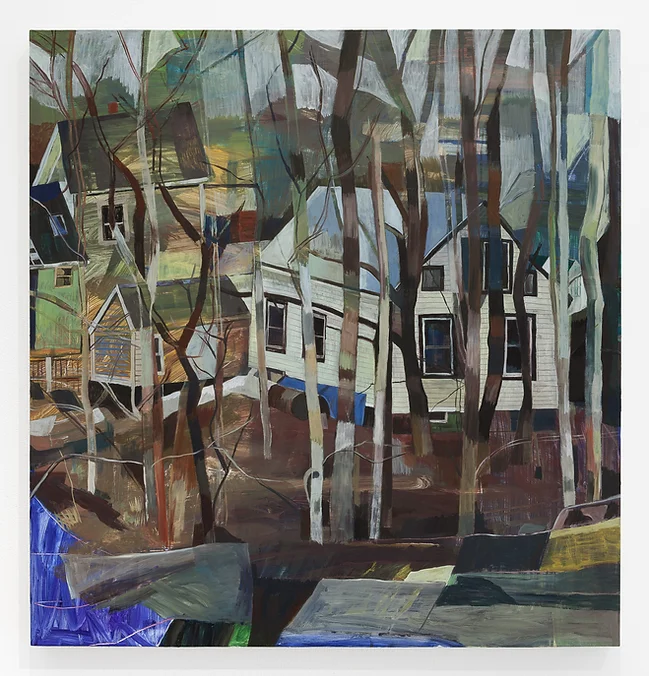

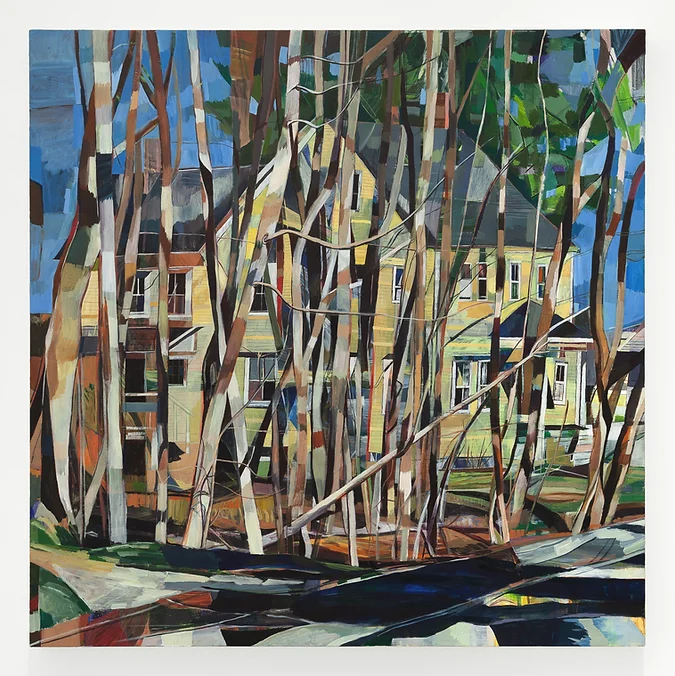

Stern’s landscapes, likewise constructed in a sparkling fugue of shifting viewpoints and positive and negative shapes, have a decidedly different emotional tenor. If the interiors seem safe, warm, and inclusive, his views of houses seen through the trees feel more alienated and marginalized, like a queering of the landscape. As in Cezanne’s views of Mont Sainte-Victoire, in which the mountain is always seen from a distance, the house in House on Mechanic Street and similar paintings feel set apart and perpetually unattainable; an effect amplified by the unstable ground at our feet. By the same token, the stockade of trees might also suggest containment, hinting at the confining, stifling, or even threatening aspects of domestic life. Either way, Stern’s landscapes present a more conflicted relationship with the idea of home than do his interiors, demonstrating his remarkably wide command of psychological expression.

In Birch Point Signs, Stern inverts this relationship, putting the viewer in the position of an inhabitant looking out at the world going by. Although a formidable gate is swung open, a cluster of signposts blocks any approach. We can’t see what the signs say, but it’s not hard to imagine that they’re prohibitive. At the same time, the vigorous and fluid brushwork depicting the path itself suggests an unimpeded but covert movement between the foreground and the background – that is, between the artist (or ourselves) and the outside world.

This ability to work at two levels at once – the private and the public, the text and the subtext – signals a deftly couched and implicitly queer perspective in Stern’s work, which nevertheless speaks to anyone whose inner life doesn’t always find connection, affirmation, or security in the world at large. Stern embodies subtle observations and implicit expressions naturally into the breadth of his image-making. This is the sign of an enormously gifted and highly sophisticated young painter making a unique, poetic, and socially significant contribution to contemporary art. It’s exciting to imagine where his work will lead next.

“Jay Stern: Awning,” Grant Wahlquist Gallery, 30 City Center, 2nd Floor, Portland, ME. Through August 17, 2024

About the author: Mark Wethli is a painter and the A. Leroy Greason Professor of Art Emeritus at Bowdoin College.

From now I want paintings without paint, and frames that do not tighten meanings. Sculptures must be 4-D and made without AI but by intuition. And with Cezanne: stop before finishing or a dead-end. About time: find a solution for its devastating effect upon living and dead matter.

This article and its subject are the best things I’ve see on any of the several similar blogs or sites that I look at regularly. Stern magnificently gifted and he has created a compelling body of work which has had a profound effect on me as an artist. He is head and shoulders above most of the claptrap that so fascinates the cognoscenti in NYC. Thank you 2Coats for this look at Stern’s work.