Contributed by Anna Gregor / It is a relief when the curator of a group show doesn’t tell viewers how to understand the work selected and lets it teach them how to see. “Pedagogy of Tears,” on view at Duckworth Gallery, is one such show. No abstract noun is exalted into a title and pretends to make simple sense of the works presented. No press release predigests the viewer’s experience. The relationship between the works is essentially human: the eight included artists have been colleagues at different times and institutions, and their time teaching together has resulted in friendship and collaboration.

While friendship might be detectable from common conceptual and formal interests evident in the works, the diversity of medium, subject matter, and overall form makes clear that these teachers do not belong to a “school” or -ism. What they share is teaching as a way of life, a constant undertaking integral to making art: a reciprocity between openness and determinacy, play and rigor, doing and undergoing. Each artist is also a student, committed to continually learning from prior work, art history, past selves, materials, and mistakes, and from the artwork itself as it comes into being.

Four of the lessons I learned from this show:

Patricia Miranda’s A Round of Roundes II suggests that art begins with an individual’s impulse to make life beautiful, as expressed in the vintage handmade doilies and embroidered aprons that Miranda has collected, archived, and pinned together into a monumental circle. The piece becomes a collaboration of all those women, most no longer alive, who spent countless hours designing, decorating, mending, and cleaning these objects. Their aesthetic impulses, once limited to the domestic sphere, now, in the gallery, take their place as fine art while retaining the intimacy and humility of individual labor.

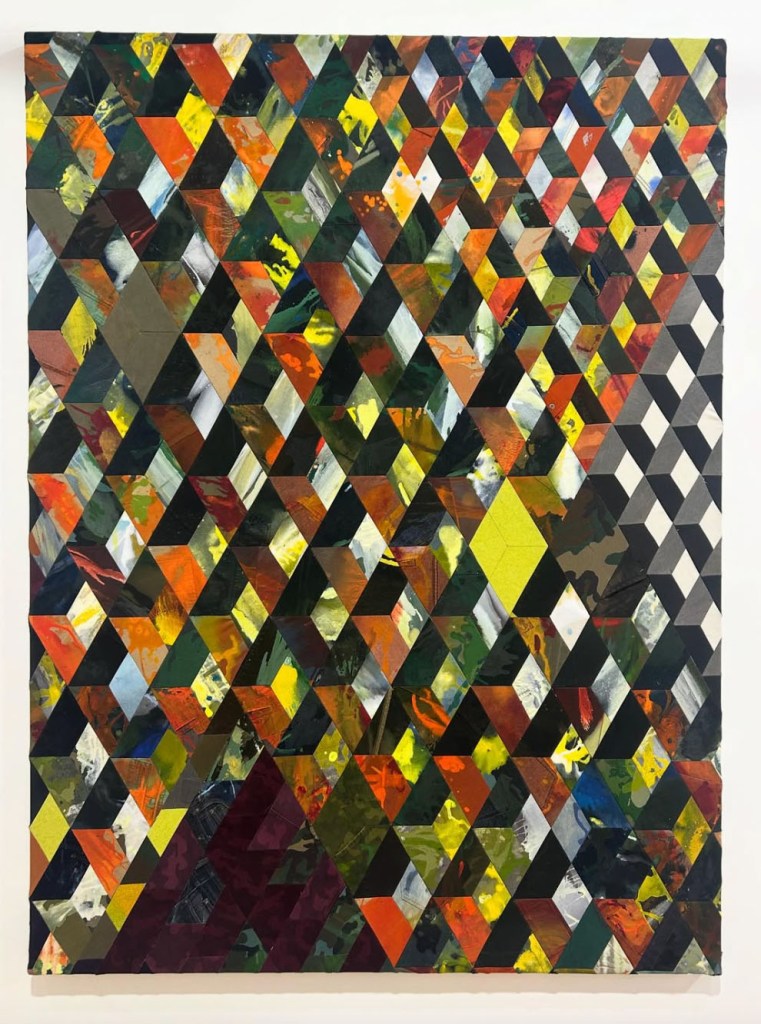

Jonathan VanDyck’s Coming to a Head similarly begins with worn clothes but moves on to portray the history of art as the homogenization and disciplining of human bodies. Denim and twill pants, once conformed to living bodies, are cut into parallelograms, sewn together, painted, dyed, and stretched on bars. From a distance, the piece reads illusionistically, like a grate or screen. Up close, the seams, pockets, and faded fabrics, rubbed thin and faded where bodies once pressed, recast geometric abstraction as a narrative of containment and dehumanization. Abstraction, in VanDyck’s hands, no longer floats above history but is grounded in the human experience of being embodied.

For Craig Stockwell’s installation, The triumph of painting over death (after Gesina ter Borch, 1660), painting is a means of marking time and making sense of its passage, a tradition marked by grandeur and violence. Representations of past personages and paintings, with scenes of violence or its suggestion, float in a world of faded hues where text abuts images without explaining. In the gallery, the paintings have become quiet, ambivalent, faded, and personal. Under the two large canvases stretched directly on the wall, rows of smaller paintings are stacked, facing away from the viewer, dates written on their verso to signify the march towards death, an inevitability to which the artist submits without losing hope.

Gaby Collins-Fernandez’s Untitled 1 suggests that the self, the perennial subject of painted portraits, is not an eternal soul but a construction mediated by historical narratives, personal memories, and contemporary technologies: a distorted selfie alongside the Venus de Milo, screen glitches, TV interference, glimpses of thread, a photographed arm, an acrylic seam, and bunches of synthetic fabric that echo the peaks of impastoed paint. For this painting, the self is built the same way a painting is: through learned techniques, habit, accident, and visual memory. And, like painting, it is contingent: stretched over bars hung on a wall. Works by Brian Bishop, Lucinda Bliss, Amy Theiss Giese, and Jason Stopa promise further insights.

Both teaching and weeping are natural and reasonable responses to an open and unknown future that passes through our fingers on its way to becoming fixed and foregone. We weep when we’re overwhelmed by what has been lost, by what is fleeting, by what might be but is not. In the face of finitude, teaching is a heavy responsibility: to select from the past what is worth keeping and to bring oneself and others into a coherent present that welcomes the future.

“Pedagogy of Tears,” Duckworth Gallery, 169 Coffey Street, Brooklyn, NY. Through November 2, 2025. Curated by Craig Stockwell. Artists: Brian Bishop, Lucinda Bliss, Gaby Collins-Fernandez, Amy Theiss Giese, Jonathan VanDyck, Patricia Miranda, Craig Stockwell, and Jason Stopa.

About the author: Anna Gregor is a painter and occasional writer about painting based in New York City. She received her BFA from Parsons in 2019 and her MFA from Hunter College in 2025.