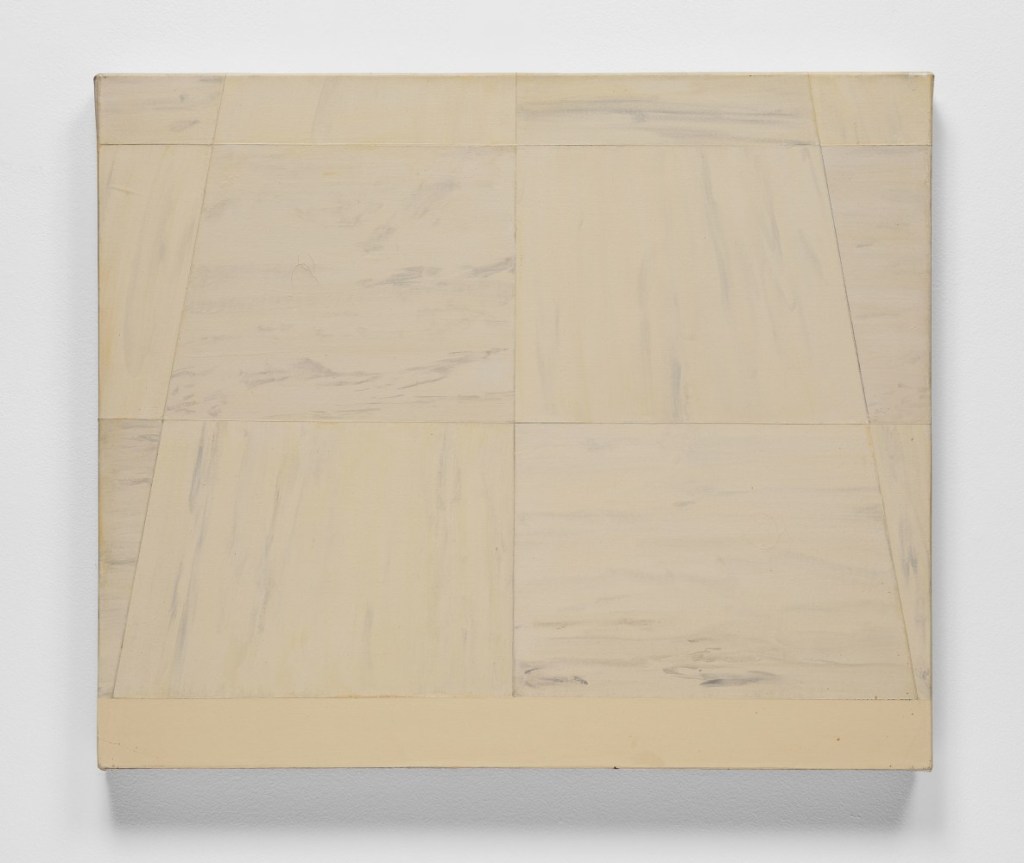

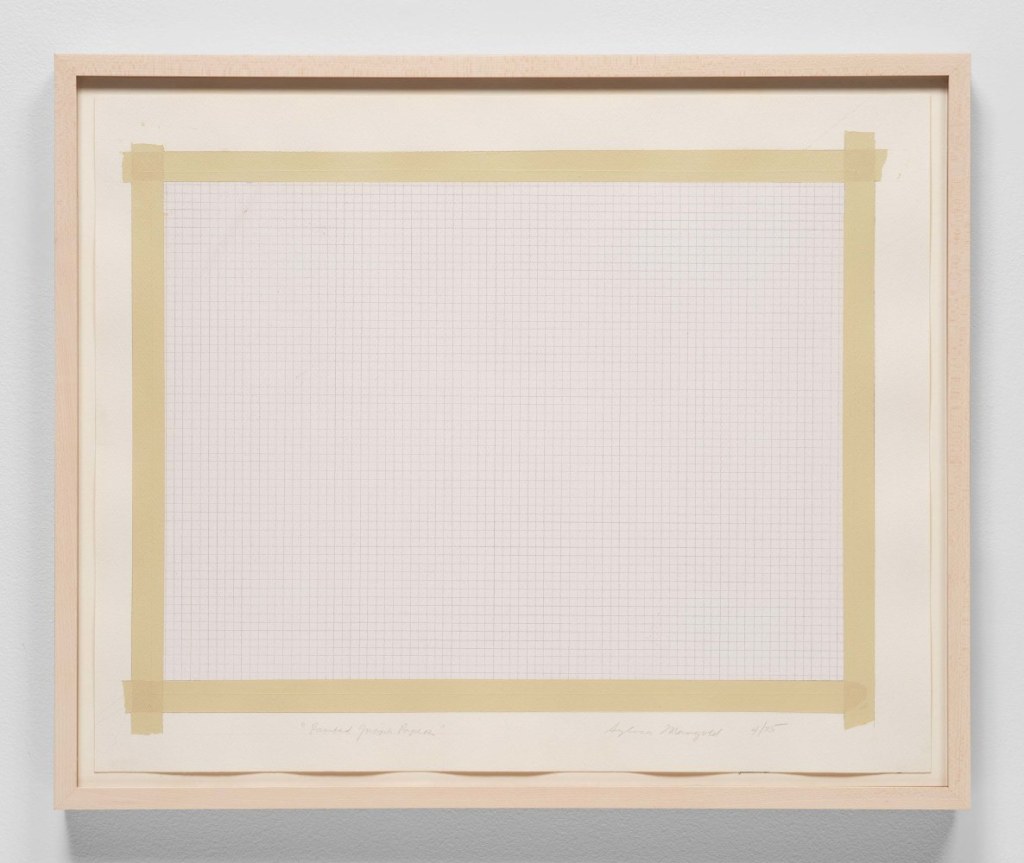

Contributed by David Carrier / As the title “Tapes, Fields, and Trees” indicates, the exhibition of ten works by Sylvia Plimack Mangold at Craig Starr Gallery draws on three bodies of her early work. In the mid-1970s, she made Minimalist paintings of tape measures. Pieces like Taped Over Twenty-Four-Inch Exact Rule on Light Floor, however, reveal a surprising poetry in seemingly prosaic subjects. Then she painted grids, like the one in Painted Graph Paper. Finally, in a remarkable transition, she drew a window looking out on a landscape and then depicted trees in that landscape as in The Pin Oak.

Transitions consume art historians, who take pains to understand why a successful artist would change styles. A tree, of course, is very different than tape and a grid. Of assistance here is a photograph in the accompanying catalogue showing Sylvia and her husband, Robert Mangold, at their New York City apartment around 1966. While they look happy there, it is cramped, so it’s unsurprising that they soon moved to a more spacious country home. It also helps to know a little about her life. On this score, take it from a senior critic: if a well-known artist invites you to her house for lunch, accept the invitation, for besides getting fed, you may learn something useful about her art. When I dined with the Mangolds on a windy day many years ago, their worried conversation centered on a magnificent tree on their property that the impending storm threatened to blow down. They fretted not just because it might hit their house, but also because the tree that was one of her favorite artistic subjects.

In this light, it was to an extent circumstantial that Sylvia Mangold moved from purely artificial subjects to nature – a very traditional subject – and on the surface not so mysterious. But landscape in particular is freighted with art history, which, for an informed artist like Mangold, no doubt also came into play. As Helen Molesworth puts it in her marvelous catalogue essay: “How we see has been inflected by 500 years of perspectival painting.” Julian Bell has also taken to depicting trees, thinking, he has written in his book What is Painting (1999), about “basic topologies of over, under, sideways, down and in fact all the modalities that are impossibly hard to verbalize because they are so very basic . . . That we stand on solid ground; that yet we look up and out onto emptiness; that between the two, we live in a restless and excited relationship with light. A way to describe this dramatization might be to say that the pictures create a sense of wonder.”

This philosophical exegesis is required, Bell told me, to understand why he paints nature. Of special interest with respect to Mangold’s trees is his query that “when painting landscape, where is the subject in relation to the spread of the world? What makes a subject? – standing-up-ness? contained-ness? directedness and mobility? What constitutes a place, in space?” Thus, the concerns of two very different artists, an Englishman and an American woman, converge. Mangold could have just stuck with Minimalism and grids and remained comfortable enough in career terms. Though biographically and aesthetically quite explainable, her boldness in shifting so gracefully to images of nature was also admirable.

“Sylvia Plimack Mangold: Tapes, Fields, and Trees 1975–84,” Craig Starr Gallery, 5 East 73rd Street, New York, NY. Through January 25, 2025.

About the author: David Carrier is a former professor at Carnegie Mellon University; Getty Scholar; and Clark Fellow. He has published art criticism in Apollo, artcritical, Artforum, Artus, and Burlington Magazine, and has been a guest editor for The Brooklyn Rail. He is a regular contributor to Two Coats of Paint.

NOTE: We’re finishing the fourth week of the Two Coats of Paint 2024 Year-end Fundraising Campaign! This year, we’re aiming for full participation from our readers and gallery friends. Your support means everything to us, and any contribution—big or small—will help keep the project thriving into 2025. Plus, it’s tax-deductible! Thank you for being such a vital part of our community and keeping the conversation alive. Click here to support independent art writing.

This is a great show and I really enjoyed reading this essay. I agree wholeheartedly with your conclusions and Mangold is well with her conceptual mode of the floor and ruler with the trees and tape. The obvious call to flatness, materiality, and her actual experience in nature is evident and love that she went there.