Contributed by Rosetta Marantz Cohen / Rare among contemporary artists, Hung Liu, who died in 2021, chronicled the trauma experienced by the Chinese diaspora in the aftermath of the Cultural Revolution. Her paintings, currently on view at Ryan Lee, vividly depict a female artist’s efforts to reconcile the terror of China’s recent past and the “otherness” she experienced after her emigration to the United States. The exhibit seems especially poignant now as questions about homeland, memory, and trauma resonate with such immediacy.

Liu’s life tracked a dramatic unfolding of world events, lived first-hand and then watched painfully from afar. Born in 1948, she grew up in the early years of Mao Zedong’s revolutionary rule. Her childhood spanned the first years of the Agrarian Reforms that redistributed land to the peasants, followed by the Five-Year Plan, the Great Leap Forward, and the Cultural Revolution itself. In 1968, like most able-bodied Chinese in their twenties, Liu was taken to the countryside to be “re-educated,” doing manual labor on a government farm for four years. She was then sent to Beijing to be trained in Social Realist mural painting. She obtained a passport and visa to the United States 15 years later.

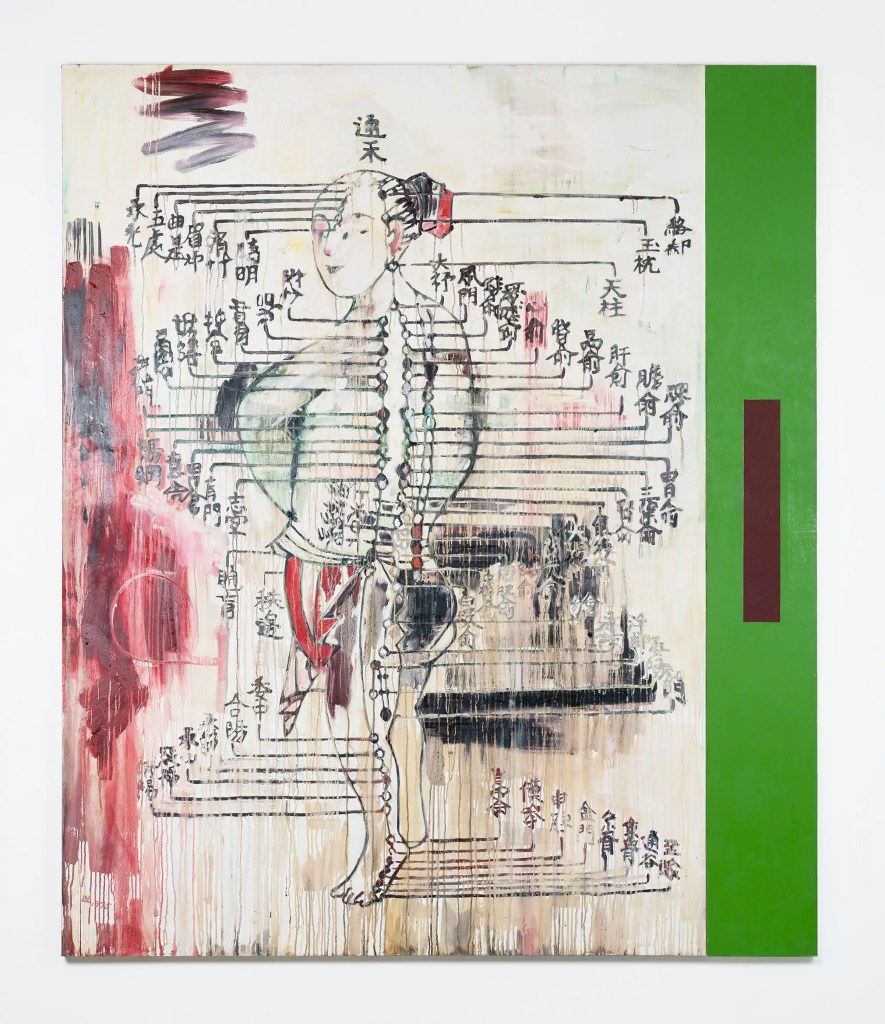

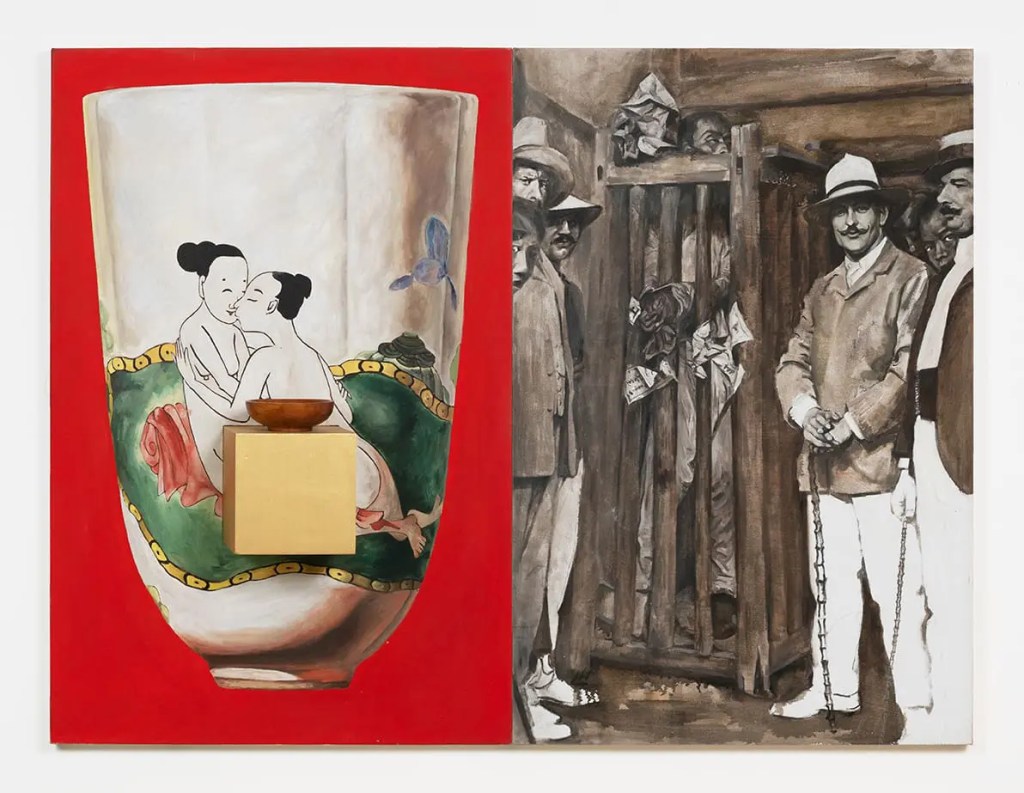

A novel and diverse set of influences–Abstract Expressionism, Minimalism, feminist criticism, and deconstructionism–inform Liu’s work, which integrates Eastern and Western iconography and formal techniques. Many paintings are generated from Chinese archival photographic images as well as text, medical diagrams, and woodblock-style line drawings. Paint application varies among hard-edge, drip, pentimento, and color block. Three-dimensional objects are occasionally affixed to a painting in spatially disorienting ways, underlining both the political and the personal nature of her work and the range of traditions on which it draws.

Liu is at once a very Chinese painter and a very American one. Exemplifying this duality is the striking diptych Red Bladder. A large male body, positioned like a Chinese medical illustration, is partly obscured by smeared kanji running along the left and right sides of the diagram. A blood-red stain trails down one side of the canvas. A color-field green slab fills the other. Antique and modern, messy corporeality meets antiseptic Minimalism.

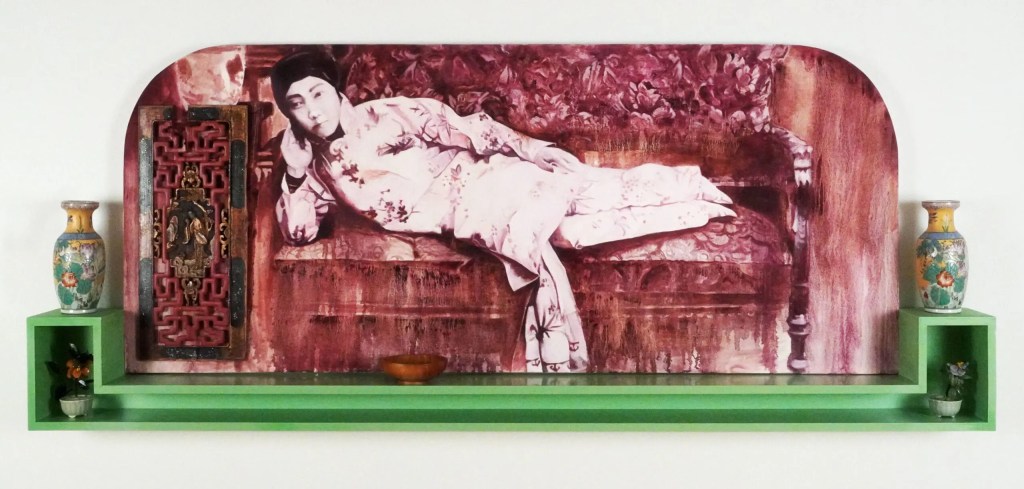

In another series of paintings from the 1990s, Liu uses early twentieth-century studio photographs of courtesans as source material for large portraits. In Fan, a large, sepia-tone image of a young girl stares boldly at the viewer. Her affect is flat, her fan half opened so as to obscure her dress. The canvas is shaped in the arched form of a Western icon, reinforced by the three-dimensional altar-like platform on which the image is set: a lime green wooden shelf, flanked by matching, brightly colored oriental vases of the sort created for export. In Olympia II, a young prostitute lounges on a couch in a flowered cheongsam and trousers, her expression direct but impenetrable. Like Manet’s Olympia, she leans on an elbow, legs crossed at the ankle. Our eyes are drawn not to nakedness but to her tiny feet, deformed by bounding but pointing forward.

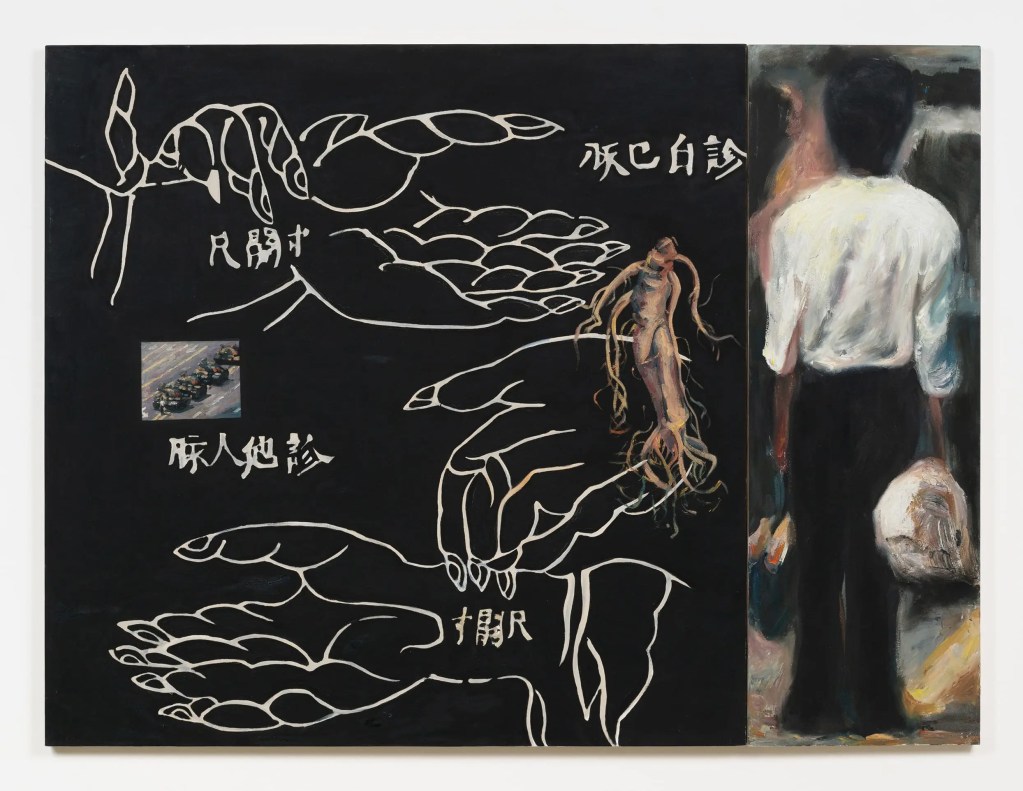

The grandest painting in the show is the title diptych Pulse. It is the artist’s response to the 1989 Tiananmen Square protest and massacre, which Liu watched in horror from her home in the United States. The painting seems to be a meditation on the limitations of seeing from afar. Immense and traumatic historical events are unavoidably filtered through media or edited in witnesses’ retelling. The painting is composed around the famous photograph that appeared in newspapers of the “tank man”–the unknown protester who stood before advancing tanks holding two white plastic grocery bags. He is reproduced on the left of the diptych as a tiny snapshot-size image. The image in the right section is larger-than-life, filling the whole canvas. In both, he is blurred and unknowable, looming as an emblem of fierce courage. The rest of the painting consists of what appear to be antique medical illustrations–white lines on black ground, depicting hands taking the pulses of other hands. A ginseng root dangles over the black ground. The painting thus encompasses the rooted and rootless, the loved and feared, the intimate but unknowable.

The works on view at Ryan Lee are history paintings, incorporating people and events that took place wholly in the past. But in their visual power and thematic universality and timelessness, they recall William Faulkner’s famous observation: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Political oppression, female exploitation, and human conflict persist, remaining visceral and immediate.

“Hung Liu: Pulse, 1989-1996,” Ryan Lee, 515 West 26th Street, New York, NY. Through June 22, 2024.

About the author: Rosetta Marantz Cohen is the Myra M. Sampson Professor Emerita at Smith College, and a painter.