Contributed by Rob Kaiser-Schatzlein / In 2011, I met Jim Gaylord when he lectured at my university in northern Minnesota, and we’ve kept in touch on and off ever since. His studio was the first I visited after I moved to NYC, and Jim reappeared on my radar recently when I heard he was in a show at Jeff Bailey in Hudson. Last week I checked in to hear what he had to say about his latest work.

Rob Kaiser-Schatzlein: How do you start a piece?

Jim Gaylord: Well, a year ago the work was all based on found film stills, and now I am taking sections of those pieces and reworking them. I like the idea of filters, taking imagery and separating it from its content. So the prior paintings are now just a point of departure, like the film stills were. I always need some kind of thread to get me rolling. Then maybe I push this part and take that other part away. Almost all the smaller works that are up now are derived from sections of the larger pieces. I call them “quarter studies” because the first one started as literally a quarter of one of the larger works. They’re not all exactly a quarter anymore though.

RKS: But they’re cropped sections of earlier work.

JG: Yeah, there is this degree of chaos in the larger work that I like. But it’s also good to focus on something that is happening. In this new bigger piece [Bad Gateway] I was really interested in this one little passage that I was working on and how different it was from a passage that was just a few inches away. It’s almost like they’re these little places you visit on a road trip that you keep coming back to in your mind. It also makes me think of a larger piece I was doing that wasn’t working. I ended up cutting it up into little pieces [pieces roughly 9 x 11 inch sections on the cutting table, some are larger or smaller] to try to figure out what actually was working. I came up with several smaller pieces. I learned a lot about that painting just from focusing on the parts within it that were working even though it wasn’t working as a whole.

RKS: How do you know when it’s working?

JG: Well, I don’t know if there is a rule, but it’s just formalism.

RKS: Straight formalism?

JG: It’s what pushes from one step to the next. Then within that discipline I can do these odd things. I’m more interested in surprises right now. Doing something that I wasn’t expecting to happen. Or maybe I have a feeling of what’s going to happen, but when I’m making the study and then go on to make the actual piece there’s a difference with what actually takes place. You have to respond to that. Stepping away from it for a while helps me to know if it’s working.

RKS: How long?

JG: I don’t know, I like to take pictures of the paintings with my phone and then look at them later in some totally different place, like in the gym or on subway. Then I see it in a different way because I’m not in my studio. Even just turning around and doing something else for five minutes. Because I get really bogged down sometimes.

RKS: It must be your formalism though, because someone else might come in and say it’s not working.

JG: Sometimes it takes time to realize that too. With that larger piece I cut up, someone was looking at it and was not sure whether it was working and I sort of knew that deep down. It wasn’t until later that I really understood why and it just had to with the way this space was distributed. Anyway, I cut it up.

RKS: How do you know when to stop?

JG: I usually tell myself that I stop when I have accomplished what I initially set out to accomplish. I have to think back in my mind about how I was feeling when I started it, figure out what was my inspiration when I started. Maybe that inspiration has changed, but then I just take a little more time with it.

RKS: So you let stuff sit around for a little bit?

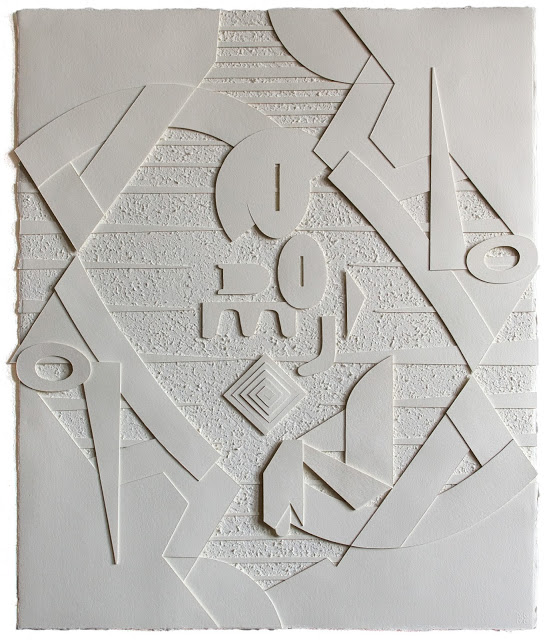

JG: I do now, I used to be really intent on starting something and finishing it before I started anything else. But now I’ve found it’s more productive to work on a bunch of stuff at once, especially if I am working on something large. If I’m stuck, I’ll just take a break and start on a smaller piece. Often times I’ll make the piece that has a connection to the larger piece and figure out what is going on, so it helps the larger piece. These two pieces [Quarter Study No. 16-17] are a result of thinking of a larger piece that was based on the same composition but I couldn’t get the colors to work. I was starting with color first. In the study [a piece of printer paper with the basic outline of the work repeated four time in a grid, each one colored in differently] I was trying to figure the colors out, but it just wasn’t working when I was doing the piece. So I decided to make one out of completely white paper. I realized that making the cut-out piece is a really different process than making a black and white sketch. So much of it is about the structure, the physical architecture of the material: what is on the foundation, what rises to the surface, what is in front of something else. When I made this–looking at it in daylight is the best way–then I was able to understand what I wanted from it color wise.

These quarter studies are very similar but not exactly the same. A limited color palette is best sometimes.

RKS: Is there a finished piece here where you remember what you were going for and you achieved that?

JG: This other totally white piece, actually [Come Back Invisible]. I had made another piece that was really complicated and I really liked what was going on color-wise. I thought there was a certain level of chaos in this piece but I’m also really interested in the basic geometry of what it’s built on top of. I wanted to do this completely blank piece that dealt just with the infrastructure. That something that’s not apparent in the finished product of these collages, the simple parts that hold them together.

RKS: But that’s important.

JG: Yeah, you don’t see the foundation when the piece is finished, and it’s something that I’m torn by… I like the idea of logic, and of getting the sense that this is this weird thing, but I feel like I understand it through an internal sense of rightness. That was one of the first attractions towards symmetry for me is because it’s logical. We observe symmetry in our bodies and faces and nature, and it gives you this sense that there are things that are recognizable. I’m interested in things that seem like they should be right and you keep searching the picture for a cue. Maybe that’s frustrating to some people, but it’s something that can help you get lost in something; take you in all these different directions. Maybe it’s like being somewhere in the wilderness and finding a creature you’ve never seen before; noticing the bodily structure and how it seems logical but not understanding what it is.

There’s this moth called the Amazonian Lantern Fly [Fulgora laternaria] whose head looks like a crocodile head. Nothing in nature is going to think that looks like a crocodile because that’s a moth. [both laughing] It has these markings that look like teeth, markings that look like eyes and it doesn’t make any sense. You look at it and think, “I know what that’s suppose to be but I don’t know what it is.”

I did a painting about that a long time ago, and I think that those moths are a good example of a kind of image that is interesting to me. An image that’s quirky. But also controlled.

RKS: Yeah like “Why did he decide to put that there?” like that hand thing there [yellow part of Quarter Study No. 5]

JG: This is a hand but it’s really a hieroglyph. Hieroglyphs are interesting but I didn’t want to make a bunch of paintings about hieroglyphs because, who needs it, you know? [mainly me laughing] That is something that looked like a hand but it was like a weird hand and you think, “why is it there?” But it also looked like some kind of lantern when I looked at it sideways. I thought it would be funny to make a piece with something that is pretty recognizable like a hand. There’s this thing [pointing], which recurs elsewhere, I don’t know where it came from. It’s this form that is like a praying mantis dancing or something [Quarter Study No. 3]. I definitely have my ideas about what certain images imply or are, but I don’t want to plant the seed too deliberately in someone’s mind. Again, that’s frustrating for some people, to figure out what I’m trying to say.

RKS: You use an overhead projector to project sketches on foundational/bottom pieces of the collage, like an architectural blueprint.

JG: It’s like a blueprint. And I use gouache on this treated clear acetate called Duralar; treated so you can paint on it. I’m using that more and more as a drawing surface, to work out things and be able to erase them and then maybe project them.

RKS: What are you using to draw on those? [it looks like very fine precise permanent marker, but with much more bold, solid, and variable line.]

JG: It’s just black gouache.

RKS: Those are very thin lines.

JG: I like using gouache because unlike marker you can wipe it off really easily.

RKS: But it’s a very solid line.

JG: All of these collage paintings are painted with mostly gouache, but sometimes other things like spray paint, pastel. This one [one of the Quarter Studies] has lines that I’ve scored with a book binding tool just to create indentations just so when I rub pastel over it, it creates a positive image.

RKS: Are these collage paintings a series?

JG: Well, until very recently I was working with film stills as primary sources of imagery and using those pretty faithfully to what they originally looking like so they ended up being abstract in nature. I was piecing the images together on the computer to make a collage of abstract forms and composing those images–then making work from that. So I guess that is a common theme that would tie most of that work together. What I’ve found recently was that there are things that kept surfacing in the work that started to feel very interesting to me, very close to me. Not personal necessarily, but imagery I felt very attached to. Certain types of symmetry, certain ways of dividing the space, kinds of patterns like the honeycomb pattern that recurs in some of these works. I began to get a sense of what it was within the film still imagery that was of interest for me. So I started to identify those pieces of the past work and cherry-pick them, and just build on that. Kind of like a personal vocabulary.

The work I was doing with the films stills pushed the original content so far that new imagery came out of it, and I really grabbed on to that process. I started to see a consistent line of thought through it.

RKS: So you were finding yourself in the work?

JG: That’s a good way of thinking of it. I think about this work as very formal spaces interrupted by idiosyncrasy. In a lot of the imagery there is some symmetry that is subtly disrupted and sometimes majorly disrupted. Then there are patterns like these ones that could be flowers or fried eggs [Quarter Study No. 8]. And there are things like a strange piano key concoction, or something, I don’t know what it is. But formalism coexisting with something that is quirky is something that has surfaced in the work.

RKS: Do you have a pictorial problem you remember solving?

JG: This is a good example [Mermaid with Cowboy Boots] of a compositional thing that I figured out over a period of time because I had to do so many different studies for it. The problem was that there is this clear relationship between large and small in a lot of the work and there was this question for me of how much density can there be in this piece before it just becomes impenetrable? I started with one concept that was satisfying, but it was so very symmetrical and didn’t convey as much of a contrast between large and small. I felt like that alone wasn’t interesting to look at, just in terms of scale. When you think about doing a bigger piece you have to think about why it’s that scale, why not make it smaller. There’s also a problem when the symmetry isn’t compelling enough. There’s a sense on the periphery of this piece that there’s a symmetry, but it�s being broken down in places. Two curves are repeated but one is broken down; I thought of it as the symmetry gradually collapsing as you got into the center.

I wanted to figure out how I could acknowledge the scale more consciously.

RKS: And how did you do that?

JG: The shapes came about from grabbing bits from past work and just trying different combinations and overlapping them and then using the digital glitches of that process as tool. There are pixels in the center there. It’s the same issue I dealt with in Bad Gateway. Actually it seems to come up over and over again.

RKS: Does your handling of the large/small issue legitimize the larger works?

JG: It does. I tend to think of the small works as quieter moments.

RKS: And you have to have an excuse for being so loud?

JG: Yeah, that’s something that I struggled with in school. I didn’t know when to make a piece big, versus just on a page in your sketchbook.

With making these collage paintings there’s a certain comfort you begin to feel by holding just a paper fragment in your hand. I realize the scale often just feels right in relation to the fragments. It’s also why it’s good to see them in person rather than in reproduction because there’s this certain three dimensionality, and intentional use of shadows. There are also things that poke out and pop up from the picture plane. Some is just a result of the physical properties of the paper. Often I’ll have to work against it, if something is popping out too much. But in general I notice those times and let it happen.

RKS: That makes the painting very tactile for the viewer; I don’t know if that�s part of it but it helps a person imagine holding these collage fragments.

JG: Yeah, there is a way we look at sculpture that is different than how we look at painting. I feel that has become part of the way that I look at these because there definitely is something that is happening with the material that sometimes beyond my control. With this all blank piece up here [Come Back Invisible] I was folding it and I had to start soaking it in water so that it wouldn’t tear.

RKS: There are some part where you abraded the paper too.

JG: Those parts I took a rasp, which is a roughening tool, and exposed the guts of the paper. It creates another layer of space for me, without having to incorporate another material. For me, looking at this work it’s really important to me that it’s all made up of the same material, because the problem that I have with collage sometimes is that I feel overwhelmed by the variety of elements. And not knowing whether I’m supposed to think about those items separately from all the other parts. It’s just one rule I’ve given myself, to only use this paper. As an artist you have to give yourself a set of rules to work within–otherwise you would show up to the studio and not know what the heck to do.

RKS: You’d be paralyzed.

JG: You’d be paralyzed, yeah. I once heard a writer say he didn’t know how he would ever be a visual artist because you can just do anything. It’s one of those things. I’ve had to say that I won’t paint on canvas for a while, until I feel like I have done all I feel the need to do with this material.

RKS: And you might never know.

JG: True, I might never know.

RKS: How long does a painting take?

JG: I haven’t been working that quickly lately because the work has changed in the last couple of years. I’ve felt like I have really had to sit with things.

This work I’m doing right now, I’m working on a little differently because I’m working with a bit of a deadline. It’s been helpful though because so many different studies had to happen before making the first cut. I’m not wasting time redoing things. Also, it was useful to cut-up the major shapes and not paint them at first until I really understood the fundamental structure of things. That is a problem that I was talking about earlier, that I can get too bogged down with how I feel about color. With the assumptions about color and the tricks that color can tempt you with. It can be very seductive, like “Oh it’ll be alright if I just make it this color because people like that color.” Something that has been a challenge for me is to really work out the skeleton before putting the color on and finding out if it’s going to hold together. But there are always things I can’t anticipate until I actually am in it. You just have to build your house before you paint it.

RKS: I always paint it first [laughing].

JG: It won’t work!

RKS: Do you have a favorite tactile experience in painting?

JG: I love the paper, because it’s a 300 pound weight but it’s soft, softer than other papers. It’s easy to cut and enjoyable to cut. I also enjoy piecing together the backgrounds, there is a relationship to maquetry, piecing together wood, which is it’s own feeling of satisfaction. Just seeing them fitting into place, especially because in a lot of my work there’s an interplay between different directions of brush marks butting up against one another. It’s exciting for me to see where they meet while I’m piecing them together. It’s just a simple satisfaction.

RKS: Who makes the paper?

JG: It’s Saunders Waterford 300 lb.

RKS: And it’s always this paper? Did you experiment with other papers prior?

JG: The first couple of these I used thinner paper but it just didn’t feel right. There is such a heft to this paper that makes it do different things. For the pieces that are about shadows the paper has to be a certain thickness to cast shadows. And it’s really easy to cut because it’s soft unlike, say, Fabriano paper which much much harder to cut. Someone asked me if I had calluses, but I don’t because I use this paper.

RKS: You just use the paper, gouache, a knife…

JG: Yeah, I have certain rules about the material but I’m okay with changing what I apply to the paper.

RKS: You’ve fixed some of the variables.

JG: There have to be surprises, but there has be some consistency for me too. I have to know, for example, how it’s gonna fit together and hold together so it doesn’t fall apart, because there is a literal structural integrity to the pieces.

RKS: Is there a certain time a day you usually paint? Or a certain time you shoot for?

JG: In terms of working, I love working at night because it’s quiet in the building, low amount of distractions. Usually 7 pm to 11:30 pm is a pretty productive time. I do try to get home to get to bed in time to be here again in the morning. But you go home and you have all these ideas in your head and it can be hard to get to sleep.

RKS: Do you do any work at home?

JG: Not really, but maybe I’ll have a picture of the work on my computer and I’ll play around on Photoshop making certain little changes. But I tend to prefer working in this space. I mean, all my stuff is here.

“Eat a Peach,” with Jim Gaylord, Douglas Melini, Loie Hollowell, Carl D’Alvia; Jeff Bailey Gallery, Hudson, NY. Through October 18, 2015.

Related posts:

Interview: Loie Hollowell in Sunnyside

Summer in wartime

——

Two Coats of Paint is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution – Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 United States License. To use content beyond the scope of this license, permission is required.

Jim's work is always great–but these new pieces are fantastic– and appreciated the questions about process and intention.