Painter Elisabeth Condon divides her time between Manhattan and Florida, where she currently has new work on view in “Tempus Fugit,” a solo show at Emerson Dorsch Gallery. Two Coats of Paint invited Condon to share ten ideas and influences that shape her ebulliently expansive paintings and installations. The artist’s influences are near and far, from her eloborately designed childhood home in California to the Astor Chinese Garden Court at the Metropolitan Museum and the furniture Japanese designer Shiro Kuramata crafted from industrial materials. Kinetic and vigorous layering are crucial to Condon’s process.

If a single image could summarize a life, this photo of my mom’s bedroom would do it. Taken around 1974, when my mother was 39 and I an adolescent, she had just decorated her dream home, honing a vision I had long pushed back against. Now, her mis-en-scènes prompt me to new interpretations of a confluent consciousness, layering seen and unseen. Not long ago I inherited this wallpaper pattern, inexplicably divided into a tiny, crumpled piece of lattice wallpaper and a piece of fabric with plant forms that unite in the wallpaper. Did she special-order it?

The Peabody Essex Museum website recounts how James Drummond, an importer for British East India Company, after 20 years working in Guangzhou, commissioned a Chinese artist to paint wallpaper for his home, Strathallan Castle in Perthshire, Scotland. The Musuem has mounted all 19 panels with sound and details, showing that décor at room scale can be a form of installation that furnishings extend into dimensional space. In this way, décor becomes an artificial landscape. I feel increasingly pulled towards tableaux in which painting and environs intersect, including Whistler’s Peacock Room, Monet’s Waterlilies at L’Orangerie, and Halston’s midtown office in the 1970s, reflecting aesthetic aspiration at its most ambitious.

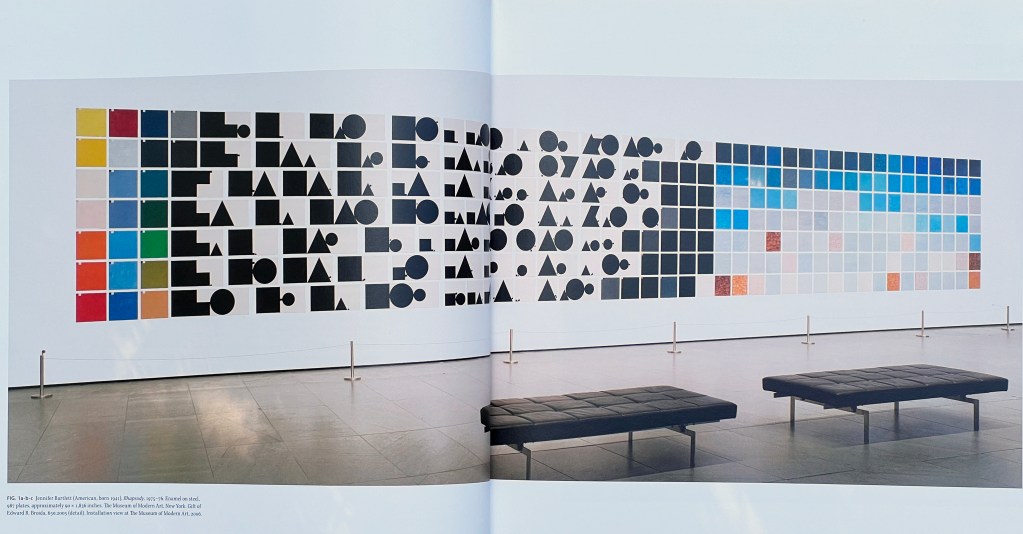

As a West Coast transplant to New York who grew up middle-class with the aspirations that entailed, painted daily, and made props for her paintings, Bartlett was an exemplar for me. She also dismissed abstraction and representation as discrete categories, preferring to include everything together, an attitude I share. Bartlett made it possible to paint about home, in what I feel sure will come to be known as seminal work. Though I would include any painting she’s ever made in a longer list, I’m going with Rhapsody, because it’s a scroll that she painted in her apartment without knowing how it would fit in a gallery (that’s how I work as well; call it improvisational), for how its unabashedly quotidian imagery of sky, tree, house aligns myriad paint applications, and most importantly on account of how she jettisoned aesthetics in favor of visual curiosity in her early working life.

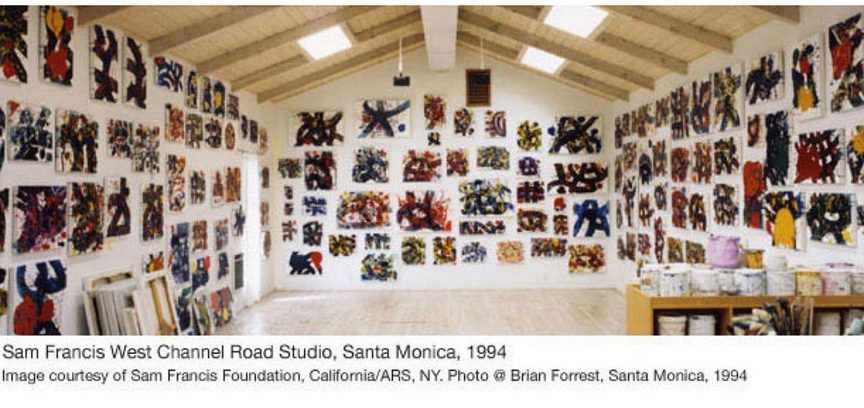

In his final year, Sam Francis painted with his non-dominant hand, producing small, wet-into-wet, woven compositions. When I first saw this image of proliferating paintings while browsing catalogs at the Strand during the pandemic, my stomach leapt into my throat as I recognized a fellow traveler. Since lockdown, I’d been painting lattice obsessively without understanding where it was headed, and this photo reassured my grounding in process. To this day, this studio image gives me courage, as does Francis’ defiantly insouciant work in general, which reflects a deep relationship to Japanese art and culture.

In the Whitney’s Making Knowing: Craft in Art (2019–22), Morton’s work was installed on the wall facing the elevators and caught my attention immediately. I instantly recognized the possibilities in working with Celastic, a heatable plastic that could be quickly molded into pillow, ladder, ribbon, and letter forms before drying. I tried it, gaining even greater respect for her skill, as it is now available in small quantities that take dexterity to shape at speed. Celastic eventually led me to Tar Gel, so I feel grateful to Morton for pointing the way. I’d seen her work earlier in “Still Point at the Turning World” at The Drawing Center in 2009, but it did not resonate then as much as it does now, fashioning emotion into home-made forms that express or map connections with simple acts of folding, writing, and framing.

Who knew that Brooke Astor spent part of her childhood in Beijing, or that this park-within-a-museum built by her foundation was modeled after the Dian Chun Yi courtyard in Suzhou’s famed Garden of the Master of the Fishing Nets? My memories of pavilions there, with mossy, concrete walls framing plant formations in the tonalities of ink and mulberry paper, brought ink painting alive in three dimensions. The similarly muted palette at Astor Court unfolds in scholars’ rocks that pile up like mountains, and expansive, empty areas resembling water. In both gardens, the window designs redistribute nature into a series of interlocking views. The wood references the massive, nanmu wood beams long used in Chinese architecture as pillars, resting solely on their weight thanks to the 26 Chinese craftsmen who placed them in the museum. When at the Met, I always try to come here.

When dining sheds cropped up all over the city in the throes of the pandemic, they initially freaked me out. Now they fascinate me as updated versions of the scholars’ houses you’d see in ancient scrolls. Those structures, demarcated with a few quick strokes of ink, invite moments of rest within the larger landscape. Dining sheds are fundamentally no different, though perhaps offer more amenities. Like Astor Court, they temporarily reframe daily experience as an artificial landscape. Each shed utilizes decorative choices for a distinct vibe, from lattice, murals, plastic flowers, and lighting, to velvet curtains, gardens, and yurt-shapes. This Chelsea shed on Tenth Avenue catches my eye every time I walk past it.

Abingdon Square is the local park, and it’s really a triangle shape. It boasts bluestone pavers, meticulously manicured gardens, and Victorian-style benches and lamps that conjure Victorian-era New York in tandem with the cobblestone streets and funky taverns of its West Village environs. The park is a frame within frames, encircled by Eighth Avenue, Hudson Street, and West 12thStreet, and a black iron fence surrounds the park interior. Once you enter the park, iron fixtures define smaller areas while echoing the fence. Among the plants is a memorial plaque for the actress Adrienne Shelly, whose office was across the street on Eighth Avenue. There’s a farmers’ market around the park each weekend, and the park itself hosts a party with apple cider at holiday time, when a 20-foot-high tree is installed. I pass through the park walking home heading south from 14th Street and it never fails to inspire me.

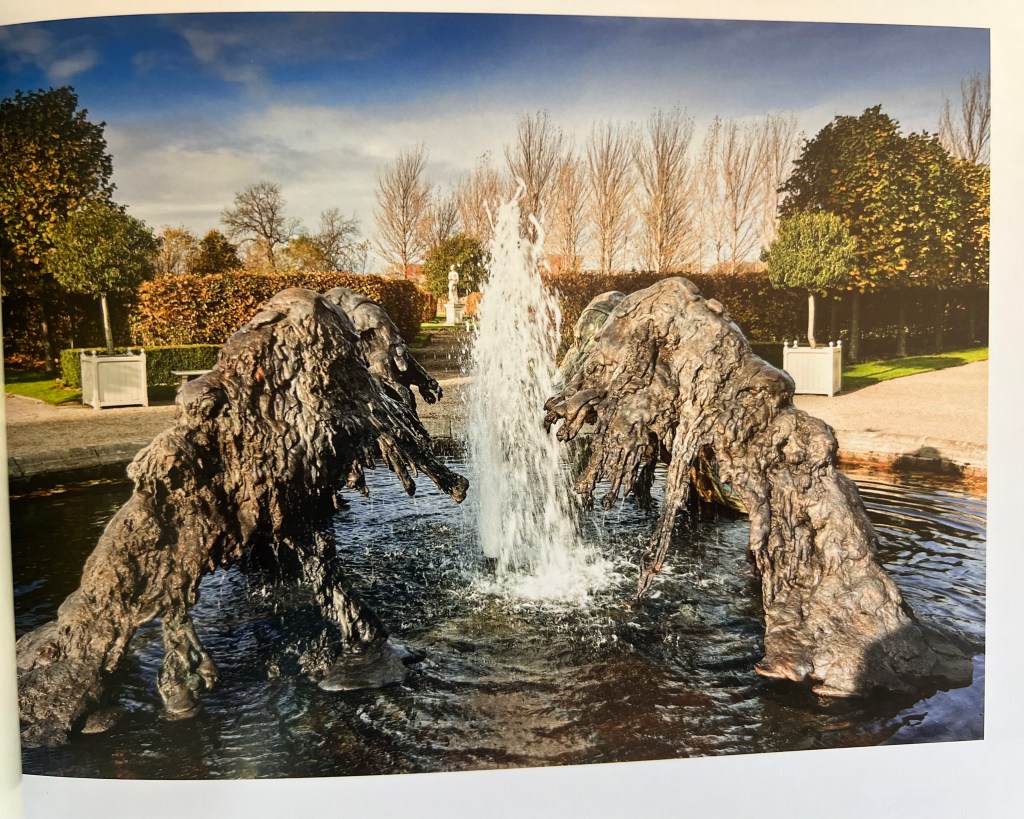

Benglis is a recent passion. I’m intoxicated by her translations of liquid into material form. In latex rubber and cast bronze pours, she disobeys artistic and societal conditioning in glorious spills. She’s also a traveler who has lived all over the world, a scuba diver and fisherman, someone who believes in “tactile thinking.” She adds: “I think we feel visually. I think that’s important. We feel, we focus. There’s an aspect of light and focusing and trying to grasp form, trying to digest the form. I almost think of myself as eating the form and regurgitating it. It’s very physical.” In Phaidon’s Lynda Benglis monograph, 067 Focus: Hills and Clouds, Nora Lawrence comments: “The addition of water, for Benglis, has always been the addition of movement. Her earliest extant fountain plans can be traced to the preliminary design for North South East West, conceived between 1977 and 1979 as a proposed monument with four gold-leafed bronze ‘wings’ cantilevered out from four sides of an obelisk – wings that from some angles resemble the wild limbs of a tree. While North South East West now exists as a fountain (with cantilevered elements facing inward, an effect to which Benglis has referred to as ‘imploding’), this early design was not intended as such; rather, it was an attempt by Benglis to bring her sculpture onto a monumental scale.” Benglis herself, in speaking of fountains, observes, “I wanted to make a form that was married to the water in a way …because all of my works are about movement.”

Kuramata, a former cabinetmaker, collaborated extensively with Issey Miyake and joined the Memphis Design Group in 1981. Duchamp and the Bauhaus influenced him as much as Jiro Takamatsu and Tadao Ando. Johanna Kawecki quotes Kuramata as saying: “There are two ways in which I usually conceive an idea. One is to start from zero, to take away every bit of a ‘thing’ that lingers around ‘that object.’ The other way is to ask ‘why,’ and to keep throwing the same simple questions at that ‘thing’.” Friedman Benda suggests that “by the mid-1970s, Kuramata was alert to the numerous possibilities of new technologies and industrial materials, choosing to turn to acrylic, glass, aluminum, and steel mesh. His ethereal yet materially precise aesthetic is exemplified in objects like the How High the Moon series (1986), Miss Blanche chair (1988) and interiors like the Kiyotomo sushi restaurant, Tokyo (1988) which is now preserved in the collection of M+ Museum, Hong Kong.” The Miss Blanche chair can be found in MoMA Room 417; designed in tribute to Blanche DuBois in A Streetcar Named Desire, it embeds that character’s delusion and fantasy into an object from daily life. Thanks to S.B. for telling me about it.

“Elisabeth Condon: Tempus Fugit,” Emerson Dorsch, 5900 NW 2nd Ave, Miami, FL. Through February 3, 2024.

Elisabeth! Fabulous! This is soooo interesting. I read it once quickly but i am all set to read it over a 2nd and third time!

When you spoke about JENNIFER BARTLETT, did you read the memoir (EVERYTHING/NOTHING/

SOMEONE) by her daughter, Alice Carriere? I did – if yu ever would like to talk about it.

Elisabeth: this was wonderful to read, it gives much insight into your work and process. Your visual exploration of lattice makes so much sense! I also enjoyed the inspirational threads we share- though you write about them so eloquently. Thanks for sharing these 10.

What a great request you were asked to respond to and your list is so fascinating in its breadth. You really -look and digest intellectually-at everything around you! I am inspired to think concretely about my influences. Thank you for sharing this.

Great work and integrating of influences. The structure arching over the chair. Pointing to Benglis just prior to Kuramata. Just a few examples of great comings-together. Both in the work and in this piece.

So beautifully written and a joy to read. I love the added insight into your work, and the peek behind the curtain into your thinking/process.

Very interesting…and must note, you have a gift for writing.

Loved your work ever since I first saw it somewhere in Tampa. This essay is amazing. Hope to get down to see the show in Miami before it closes.

Great read, Elisabeth! Favorite moments for me are your parents’ bedroom, that fabulous Benglis fountain that I’d never seen before, and the “Miss Blanche” Kuramata chair at MOMA.